The woman trying to save India's tortured temple elephants

- Published

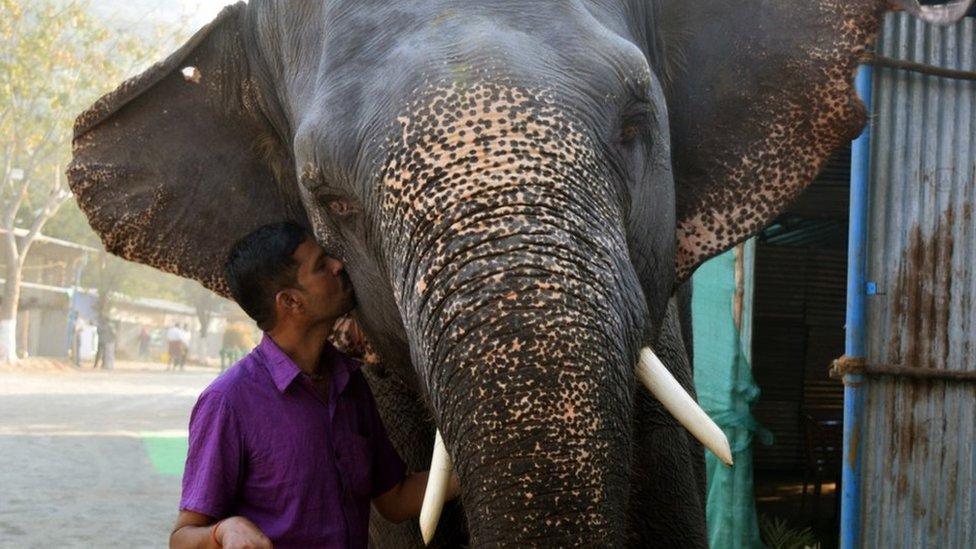

Sangita Iyer says she fell in love with the cow elephant Lakshmi as soon as she saw it

Sangita Iyer is on a mission.

As a child, the documentary maker, who was born in the Indian state of Kerala but now lives in Toronto, saw ceremonial elephants being paraded and thought they were beautiful. Later, she learned about the ordeal the animals are subjected to.

"So many elephants had ghastly wounds on their hips, massive tumours and blood oozing out of their ankles, because chains had cut into their flesh and many of them were blind," Iyer told the BBC.

She has made a documentary, Gods in Shackles, in an attempt to draw attention to the treatment of temple elephants she saw in India.

"They were so helpless and the chains were so heavy," she said. "It was absolutely heart-breaking for me to witness this."

Elephants suffer a great deal of stress during festivals, Ms Iyer says

An old tradition

Hindu and Buddhist traditions give elephants an elevated status. For centuries, temples and monasteries have used them to perform sacred duties. Devotees even seek blessings from them. The reputation of some elephants outlives their time on Earth.

Near Kerala's well-known Guruvayur Temple you will find a life-size concrete statue of a much loved elephant called Kesavan. Its tusks adorn the entrance of the temple. It is claimed that Kesavan circled the temple before collapsing and dying in 1976, aged 72. It is common to see people gather to mourn the death of temple elephants - even if they are not that famous.

"They torture the elephants to death, and after their death they light lamps and shed crocodile tears, as though they really feel sad for these elephants," Iyer said.

Guruvayur Temple owns more than 50 elephants

Ceremonial elephants are used in temples across India, but their presence is extensive in Kerala. The state is home to about a fifth of the country's roughly 2,500 captive elephants. The animals are owned by temples as well as individuals. Guruvayur temple alone has more than 50 elephants.

A lucrative business

Ceremonial elephants can bring in lot of money to their owners. Some animals fetch more than $10,000 dollars per festival, Iyer said. The money is paid by the festival organisers, as well as local shop owners and landlords.

One of the biggest names in the business is Thechikkottukavu Ramachandran, regarded as the tallest captive elephant in Asia. Ramachandran is now 56 and partially blind. He remains the star attraction during the annual elephant parade in Thrissur and even has his own Wikipedia page, external. He has run amok several times due to apparent stress, and killed two people last year, prompting the local authorities to ban the use of festival elephants. But the ban was lifted after protests.

Elephants can get scared during firework displays and run amok

Iyer, who describes herself as a practising Hindu, has been based in Canada for several years. During a trip to India in 2013, she saw elephants for the first time without their ceremonial ornaments and clothes.

"These animals were brutalised using vicious weapons like bullhooks, spiked chains and long polls with a poking spike - which is used to poke elephants in their joints to trigger severe pain," she said.

The condition of one bull elephant called Ramabadran was so severe that the Animal Welfare Board of India, external suggested a mercy killing, but the elephant was used in temple ceremonies until the very end.

"It was pathetic to watch this elephant dip its paralysed trunk into a water tank," Iyer said. "It couldn't scoop up water."

Sangita observed that this elephant was unable to eat or drink due to having a paralysed trunk

Experts say that restrictions imposed by temple authorities have prevented proper scientific studies of the physical and psychological condition of temple elephants.

"A temple by itself can never be a good place to keep an elephant," said Dr Raman Sukumar of the Indian Institute of Science, an expert on Asian elephants.

"The elephant is a highly social animal and should be only kept in social groups. Elephants should never be kept solitarily in temples, as with solitary female elephants in temples in Tamil Nadu, or with all-male groups in temples in Kerala," he said.

Chains have caused deep wounds in many elephants

Among Asian elephants, only males have tusks - which are preferred by temple authorities in Kerala. But female elephants are widely used in other parts of southern India.

In 2014, Iyer saw a captive cow elephant and was mesmerised by it, she said. "When I first saw Lakshmi, it was love at first sight."

"I put my hand beneath her neck and touched her chest. As soon as I did that, she put her trunk on my hand to smell me. They are so sensitive to smell."

Iyer sprayed water on Lakshmi and fed her pineapples and bananas. A year later she was shocked when she met Lakshmi again.

"I was devastated to see her eyes oozing out tears. She was taking her trunk tip and was rubbing herself and massaging herself," Iyer said.

Millions visit Thirussur to see an elephant parade

Apparently Lakshmi had taken food from her mahout (an elephant's handler) and in a fit of anger he lashed out at her mercilessly. One of the blows with the bullhook landed in her eye and blinded her.

In order to make an elephant obey her mahout, handlers put the animals through a torturous training routine that takes place away from temples.

"They tie and beat the elephants for 72 hours or until their spirits are broken and they obey whatever the mahouts say," Iyer said. "They are like zombies. Many elephants are just living skeletons."

Sangita's favourite elephant, Lakshmi, continues to work, even after losing sight in one eye

Authorities are now organising rejuvenation camps in Tamil Nadu and Kerala to provide rest and medical check-up for the ceremonial elephants.

"Temples in a given region should collaborate in creating adequate facilities for maintaining elephants in an environment which ensures their overall welfare," said Dr Sukumar.

Last year, Kerala's state government announced its intention to strengthen the rules governing captive elephants, but progress has been slow. Activists say even the existing rules are not properly implemented.

The temple authorities are reluctant to change, according to Iyer.

"Some are in deep denial," she said. "It is easier to deny rather than accept we are wrong and say we are willing to right the wrong."

- Published30 January 2020

- Published6 July 2017