Singapore: Jolovan Wham charged for holding up a smiley face sign

- Published

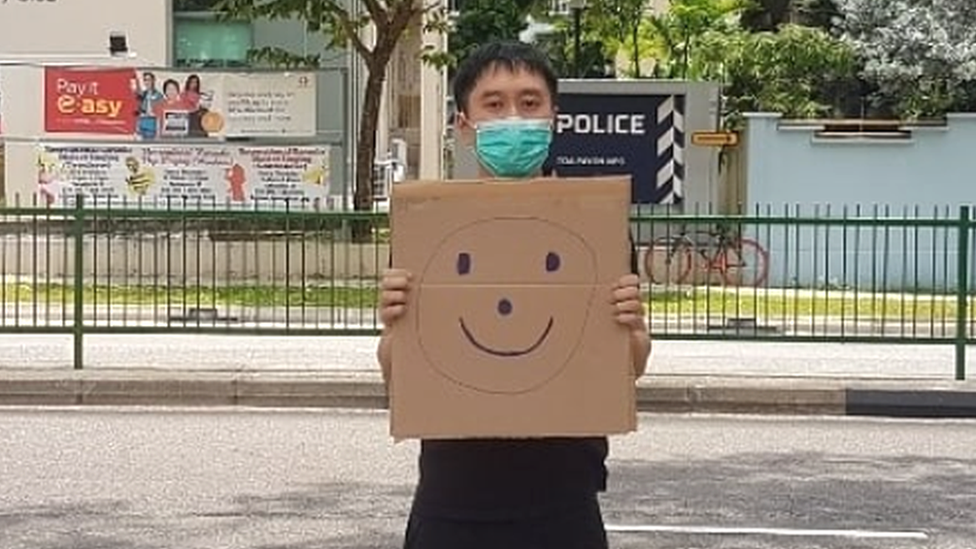

Jolovan Wham has been charged for illegal public assembly after he held up this smiley face sign

To the casual observer, it is just a photo of a man holding up a smiley face - an image used hundreds of millions of times a day in messages across the world to say "happy".

But this smiley face on a Singaporean street is different. This smiley face has landed the man holding it in court, potentially costing him thousands of dollars in fines.

And despite the risks, this smiley face has also inspired a wave of smiley faces in support.

So what exactly about this particular smiley face has upset authorities in one of the world's wealthiest and most advanced nations?

Why is this smiley face offensive?

Well, it has less to do with the smiley face, and more to do with the man holding it.

Jolovan Wham is a civil rights activist who has made a name for himself in recent years drawing attention to the issue of freedom of speech - or rather, as he would argue, the lack of it - in Singapore.

The photo was the latest in a long line of incidents involving Mr Wham which have upset the government.

Last year, it was for inviting the prominent Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong to join in a conference via Skype.

On another occasion, he held a candlelit vigil for a Malaysian man executed for drug trafficking, while a silent protest on a train also placed him in the authorities' sights.

Mr Wham leaving the High Court in March 2019 for an earlier case

To an outsider, aware of the protests convulsing the streets of Thailand and Hong Kong, it all seems rather tame.

But Singapore has exceedingly strict rules on public assembly and imposes tight restrictions on freedom of speech and the media.

It requires a police permit for any assembly in a public place linked to a cause or in demonstration of a view. The government defends its public assembly laws as necessary to maintain order and safety.

But Mr Wham rarely gets a permit. As a result, he was already in trouble for the Skype session, the vigil and the train protest when he took the photo in March.

So, why post a photo which would get him in more trouble?

For a start, Mr Wham argues it was not a protest. In court on Monday, he pleaded not-guilty to illegal public assembly.

He was, he says, just showing support for two young climate activists who had been summoned by police for questioning.

One had carried a placard saying "SG (Singapore) is better than oil" in the same spot Mr Wham's photo was taken in. The other - an 18-year-old school student - had posted photos of herself holding signs urging climate action outside the office of US oil giant ExxonMobil.

Their actions were similar to those of Greta Thunberg, the climate activist who has been praised around the world for her quiet, determined stand against climate change.

Swedish activist Greta Thunberg has inspired climate activism in young people around the world including in Singapore

Both ended up being questioned by police and having their phones seized - a reaction Mr Wham denounced as a violation of Singapore's commitment to free speech.

But his photo, he says, is not a protest.

Officials have taken a different view.

"The Speakers' Corner is the proper avenue for Singaporeans to express their views on issues that concern them, and to allow Singaporeans to conduct assemblies without the need for a permit, subject to certain conditions being met," police said in a statement about Mr Wham's charges.

If found guilty, he could be fined up to S$5,000 (US$3,700; £2,800). He has also been charged in relation to another alleged protest in 2018.

The Speakers' Corner - established in 2000 and loosely modelled on the one in London's Hyde Park - is currently closed under Covid-19 restrictions as part of Singapore's tight and largely successful measures to control the pandemic.

Has Jolovan Wham done anything else?

Yes: in fact, he has already served two brief sentences this year.

The first one-week stint in March came when he chose jail instead of paying a fine after he was convicted of "scandalising the judiciary" on social media. Mr Wham had shared a post on Facebook comparing the judiciary in Malaysia to Singapore.

A few months later he spent another 10 days in jail after he was convicted of violating the Public Order Act with the Joshua Wong conference.

It was, he says, worth it.

"Singapore is not this open and international and cosmopolitan city that it likes to present itself as," he told the BBC. "It's only modern in terms of its appearance, but highly intolerant when it comes to people just expressing themselves."

And despite the highly-controlled island state being largely successful in stamping out public dissent, two years ago Singaporean artist Seelan Palay spent a fortnight in jail after a performance he staged was deemed a one-man protest that violated the Public Order Act.

Singapore's gay rights rally has come under more controls in recent years

He had walked solo to Singapore's parliament, holding a mirror, to commemorate the detention of the country's once longest-held political prisoner.

What's more, others have started to show Mr Wham their support. He has had 200 people send him smiley faces.

Some have even been brave enough to post their own smiley face selfies, using the hashtag #smileinsolidarity.

Fearing the law, some have shared images without revealing their identity. Others have written directly to Mr Wham. "I've received many messages of support," he says. "But people are afraid of expressing themselves. They write to me privately."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

There have been detractors too, he adds, but the activist thinks "it isn't true that Singaporeans are happy with the status quo".

"There are people who are dissatisfied with these laws."

Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, said the case against Mr Wham was an "absurd prosecution".

"Singapore's government should grow up and recognise it needs to have a national conversation about what its people want in the 21st Century, and that requires respecting people's civil and political rights," he said.

Reporting by Preeti Jha.

- Published5 August 2010

- Published19 March 2020