New Zealand's Stuff news group apologises for anti-Maori bias

- Published

Stuff is one of New Zealand's biggest newspaper organisations

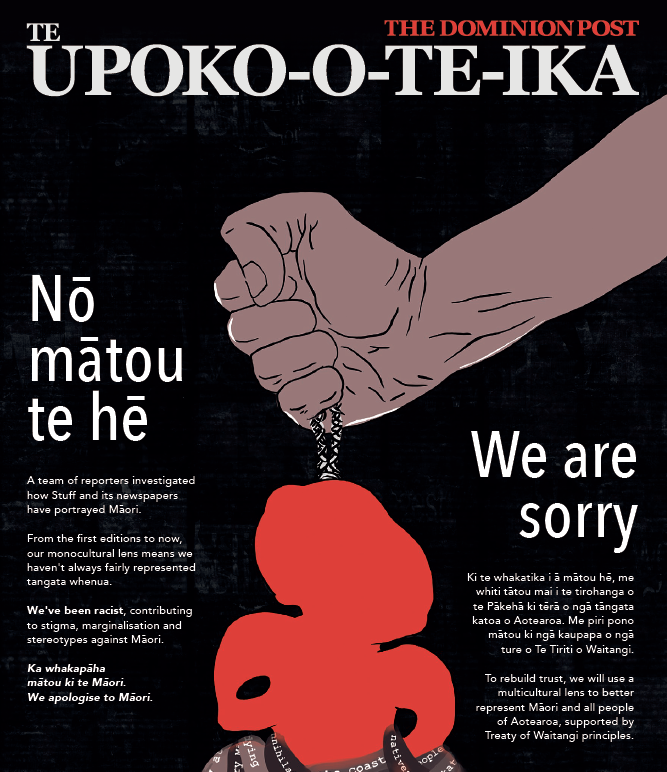

On Monday, New Zealand's Maori woke up to an apology from one of the country's biggest media organisations, Stuff: "No matou te he; We are sorry."

It came after a months-long deep dive into their own reporting which found their coverage of Maori issues had "ranged from racist to blinkered" over the company's 160-year history.

The investigation does not make for pretty reading. Scouring its papers, journalists found early, openly racist front pages and recent letters full of bile. It found a tendency to over-report on Maori child abuse cases, while playing down similar crimes in the European, or Pakeha, community. It found countless occasions where it simply hadn't bothered to ask the Maori community for their side of the story, siding instinctively with the more powerful white population.

It had, as Stuff's editorial director Mark Stevens said in an editorial published the same day, divided the country into "two separate groups, us and them".

For Carmen Parahi, the apology was personal. She had seen up close the issues uncovered by the investigation during her 20-year career as a journalist in New Zealand, and she had dedicated months to leading the investigation for Stuff. But more importantly, it meant something to her as a Maori woman.

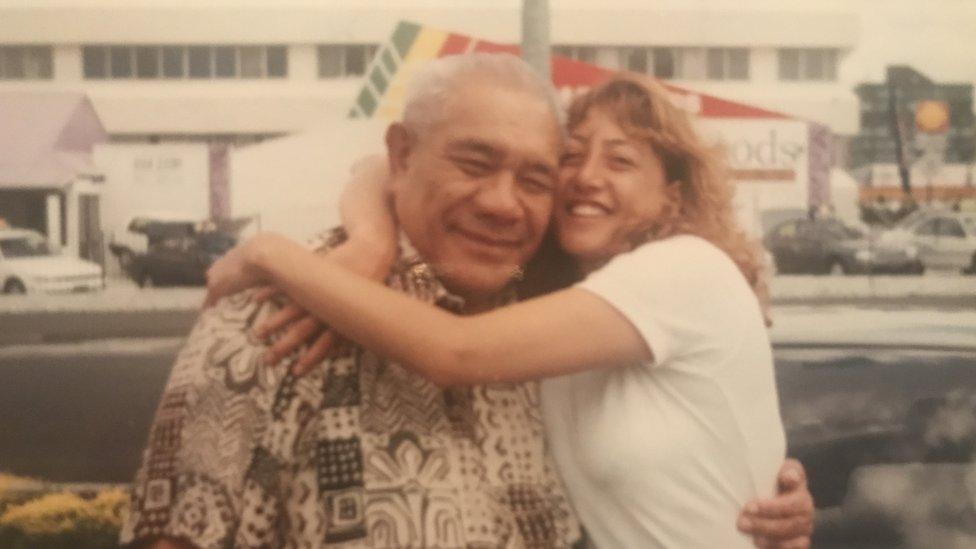

Carmen Parahi has been a journalist in New Zealand for 20 years

"Until the day it dropped, I didn't think it would happen," she told the BBC. "As a Maori woman, I have seen the impacts of how the media has portrayed Maori over generations, and felt it - because we are a collective people. Mention Maori in a story and collectivise Maori in the stories as we have been, then you are telling me that I am a child abuser, or that I am part of this terror group.

"It is all these things that the media keep saying, Maori you need to sort this out, Maori you need to do this, and that starts to play on your view of yourself."

'Savages'

Parahi hadn't needed to look far to see how the media's portrayal had affected the Maori people - she found it in the racist letters to the editor carefully pasted into a scrapbook belonging to her grandfather after he died.

"I thought, why did my grandfather keep these letters to the editor? He must have kept them because [of] what they said in those letters - 'We have got to stop them being savages'. He wants to prove them wrong. He wants to show them what it means to be Maori. That must have really hurt him. And I feel really hurt for him."

Carmen Parahi with her grandfather, a Maori All Black player, singer, LDS missionary, and labourer

Stuff's investigation found the company had, in some ways, made massive strides away from the coverage of its first newspapers. Set up by settlers for settlers, it had in 1870 described the Maori as "a bloodthirsty and semi-barbarous race".

But that did not mean it had done enough.

Take how New Zealand's mainstream media covered a series of police raids on a suspected terrorist ring back in 2007, which saw hundreds of officers swoop on a remote, majority-Maori area.

"They actually shut down the whole community," Parahi explains. "In that community, they were holding families in their homes. They stopped [school] buses, they frightened the whole community."

The first newspapers in New Zealand described the Maori people as "bloodthirsty"

The raids would eventually result in no-one being tried for terrorism. Four people were found guilty of firearms-related offences and the police eventually apologised to the community for their actions.

But the Stuff investigation found their reporting had also fallen short.

"We were so busy worrying about the idea that all these people were creating terror plots we didn't step back and we did not represent that community," Parahi says. "If this was a community in Auckland or Wellington or Christchurch, there would have been an uproar from the public about how heavy handed the police [were]. But we did not stand up for Maori. We did not as journalists take all sides against the powers and authority of the state."

File photo of a policeman in New Zealand

A few months ago, Parahi reached a crossroads.

"I love the high principles of journalism," she explains. "What I do not like is when we use a monocultural lens to get some understanding. I've been doing stories for years about institutional racism against Maori. I thought this year, why am I continuing to do this if the journalism industry could also be accused of institutional racism.

"The news media was set up in Britain. It was then imported as Britain colonised the globe. It has been very Western… it is a white perspective. It means anyone outside of that framework loses their voice.

"And personally, I got fed up with the way we were reporting on Maori. So either I leave the industry, which I love, or do something about it."

Parahi decided on the latter, and from here it was a case of "right place, right time". Stuff is New Zealand-owned for the first time in its history, and she got support from colleagues across the spectrum before approaching the company's chief executive, Sinead Boucher, with a simple message: we need to change, and we need to be more representative.

Boucher's response? "I've been thinking about this - how do we do it?"

Six months later, Stuff published its apology and admitted - loudly - it had been racist.

The Dominion Post is one of many titles owned by media giant Stuff

Importantly, it has also pledged to do things differently going forward. Among other things, the group has established a "Pou Tiaki" section, which will showcase Maori stories, with Parahi as its editor.

But Parahi is keen to stress: "This is not about me or what I want."

"This is about the whole company," she says. A few days after the newspapers were published, it dedicated seven ad-free pages to the investigation - a sign it was putting its money where its mouth is. They all know we have to be more representative."

It seems the public also know this. Yes, there have been some subscription cancellations, and a few complaints but they were two-to-one in favour of the move.

Parahi admits that she was hoping it would be three-to-one, but was quietly reminded by a colleague that a few years ago "it would have been 10-to-one the other way". What's more, the website - which is paid for by a combination of advertising and donations - had its most successful day ever for donations.

But it is the impact on the wider Maori community which really stands out.

"I cried when the news broke on Monday. I absolutely bawled," Glenis Philip-Barbara, New Zealand's first assistant Maori commissioner for children, told One News, external.

Tina Ngata says Maori people are still suffering under the legacy of colonialism

The Stuff apology was an "admission of something you and I have lived with all our lives".

"Never in my wildest dreams did I ever think this day would come," she told Maori journalist Jenny May Clarkson. "For us at the Children's Commission, we see and we hear from children every single day to live in a nation which assumes that you are inherently criminal, that will follow you around in a shop, to live with a teacher that thinks that, as a brown kid, you will never amount to much."

Reactions like this just go to show Parahi and all the other Stuff journalists' hard work was needed.

"We are always holding power to account - when will we hold ourselves to account? Journalism is part of our democracy," she points out.

And how does she think her grandfather would feel, reading the apology?

"He would have loved it."

Related topics

- Published4 November 2020

- Published12 September 2019

- Published10 June 2019

- Published24 September 2019

- Published7 October 2019