The countries grappling with their European heritage

- Published

In 1769 HMS Endeavour landed in what is now Poverty Bay

Next month, a fleet of ships will circumnavigate New Zealand to mark 250 years since the arrival of European settlers.

Their journey is part of Tuia 250, a NZ$13.5m ($8.5m; £6.8m) government initiative to celebrate New Zealand's "Pacific voyaging heritage".

Among the flotilla is a replica of Captain James Cook's HMS Endeavour, which arrived in the country in 1769 - the first European vessel to do so since Dutch explorer Abel Tasman reached New Zealand in 1642.

But not all plans have proved to be plain sailing.

After complaints by Māori, this week organisers cancelled HMS Endeavour's scheduled stop in the North Island village of Mangonui.

Anahera Herbert-Graves, head of the Northland Ngāti Kahu iwi, told the BBC that the idea was "historically confusing and quite rude".

"The celebration is a renewal of the colonial myth that they discovered us," said Ms Herbert-Graves. "We're looking at people who behaved like barbarians wherever they went in the Pacific."

She added that local indigenous groups were also insulted because organisers had not consulted them beforehand: "They just assumed they had the right to do so."

New Zealand's Ministry of Culture was not immediately available for comment.

Protests against the commemoration of European settlement have faced criticism across the region

Captain Cook continues to be a provocative figure in national history. Last year, local authorities removed a statue of the British explorer from Gisborne after it was repeatedly vandalised with graffiti.

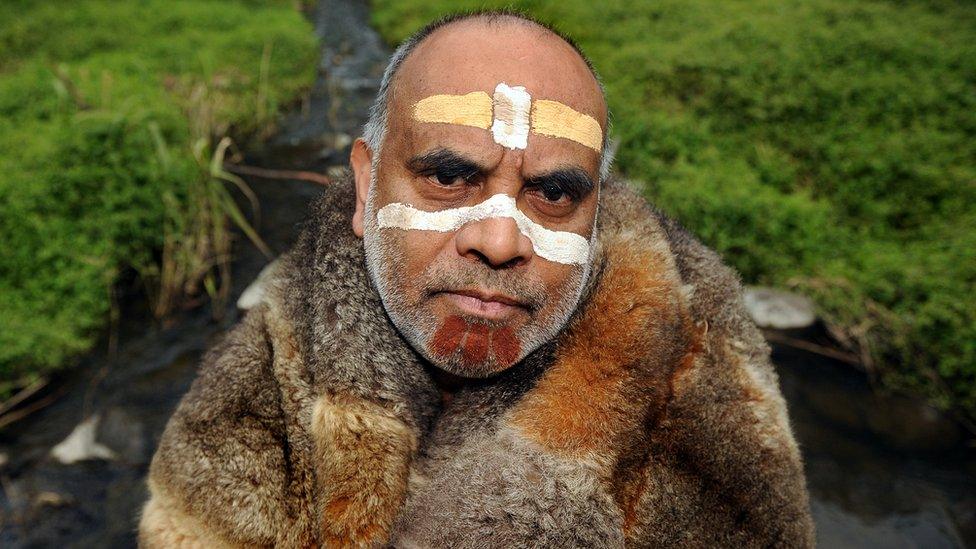

Similar protests have also occurred in neighbouring Australia, where Captain Cook also landed. Australia's government is also commemorating his voyage next year.

Many Aboriginal groups have spoken out against those plans, and the celebration of Australia Day, which marks the anniversary of British settlement. Some critics have dubbed it "invasion day".

"Nobody is denying that Cook arrived," said Ms Herbert-Graves. "What we're saying is why commemorate Cook to lead on the story? You wouldn't commemorate Adolf Hitler's contribution to modern motorways in order to tell the story of Jewish endurance."

A Captain Cook statute was vandalised in Australia last year ahead of its national day

New Zealand currently provides all people, including Māori, with legal protections from discrimination based on race.

Seven parliamentary seats are reserved exclusively for Māori MPs to ensure a basic level of representation in government. Nearly a quarter of the legislative body is currently comprised of Māori MPs.

The government has also taken measures to preserve indigenous culture. Māori is recognised as one of the country's official languages, and a publicly-funded Māori language TV station was established in 2008.

But voter turnout amongst Māori is consistently low, and the community has a disproportionately high rate of unemployment and incarceration.

Several Māori groups also continue to campaign for rights over historic land and fisheries.

'The don't really care about us'

Canada is another country that continues to grapple with its treatment of indigenous people and the impact this has had on national identity.

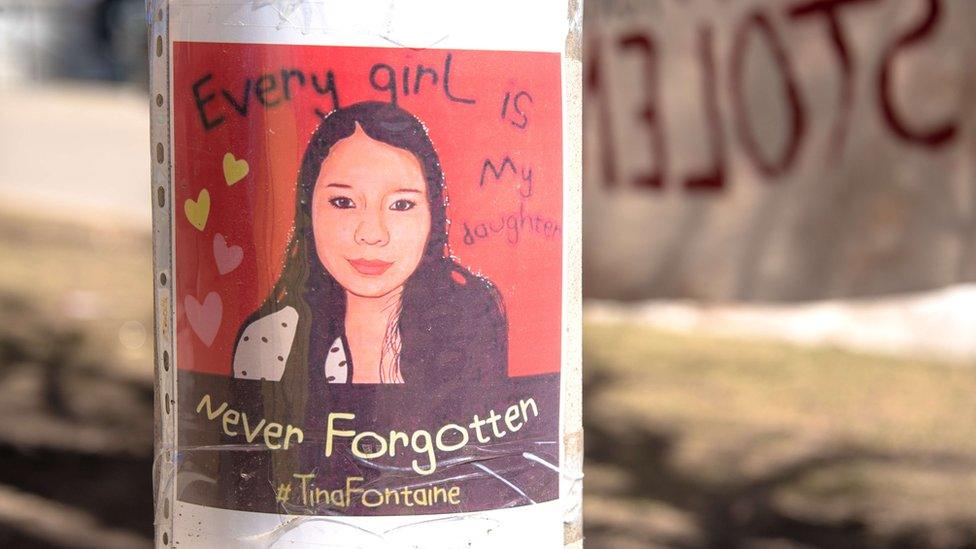

Earlier this year, a landmark government inquiry concluded that Canada was complicit in a "race-based genocide" against indigenous women.

Political and environmental activist Joseph Fisher argues that Canada was "founded on racism"

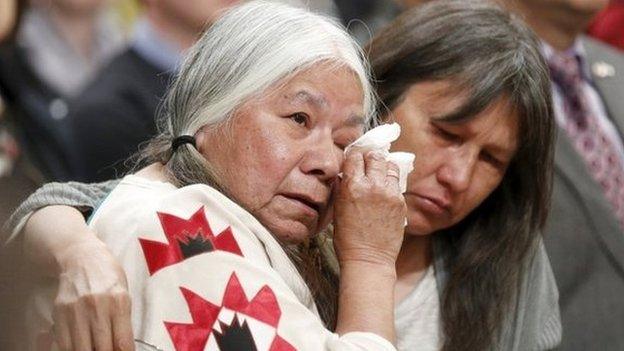

Another government commission ruled in 2015 that Canada had committed "cultural genocide" by separating some 150,000 indigenous children from their families and forcing them to live in state-run schools. More than 3,000 children died while living in these schools, while others suffered physical, emotional or sexual abuse.

Joe Fisher, whose father lived in one such school, told the BBC that celebrating Canada Day - the country's national holiday - was "a slap in the face to anybody who's not a white settler".

"Canada was founded on racism, and not just to my community," said Mr Fisher, a political and environmental activist in British Columbia.

"I'm not saying I'm not proud to live here," he added, "but to say I'm proud of being a Canadian, it's almost equal to saying I'm proud to be a member of the Klu Klux Klan."

'The nun rubbed my face in my own urine'

More than 10 years ago, Canada voted against a United Nations declaration guaranteeing certain protections to indigenous people around the world, including the right to exist.

But last year, a bill to apply the UN declaration into Canadian law passed the country's lower house, and is due to be voted on in the Senate.

Mr Fisher says that thanks to activism, education reform and media coverage, attitudes are changing in Canada as more people become aware of indigenous history.

He believes that other steps should be taken, like ending the exploitation of historically indigenous lands for natural resources.

However Mr Fisher remains sceptical that the government will push through any meaningful changes to improve living conditions and opportunities for indigenous people.

"I don't think they really care about us or they wouldn't do what they have done and what they continue to do," he said.

'It has rewritten history'

In other countries, like South Africa, governments have replaced old national celebrations in an attempt to strengthen ties between indigenous people and more recent communities.

For over 40 years, Founders Day was celebrated in South Africa every 6 April to mark the anniversary of Dutch settlement in the country.

But the holiday was abolished in 1994 after South Africa held its first election for voters of all races. The day of those elections, 27 April, is now celebrated as Freedom Day.

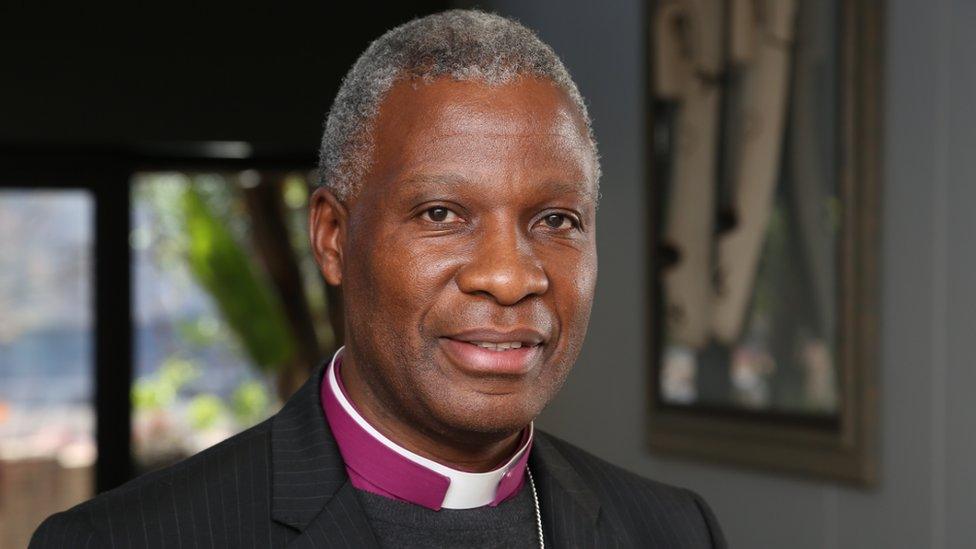

Dr Thabo Makgoba is a patron of South Africa Day

Since 1995, South Africa has also celebrated Reconciliation Day, on 16 December, in a bid to foster national unity and placate racial tensions.

The day was chosen because it falls on the anniversary of two key events in South African history: the Battle of Blood River in 1838, when a group of Afrikaans explorers defeated an army of Zulu warriors; and the founding of the African National Congress (ANC) military wing in 1961.

Critics argue that the abolition of Founders Day is an attempt to erase the country's early history and make white South Africans feel unwelcome.

Supporters, meanwhile, say that Founders Day commemorated an era of rampant inequality among South Africans.

For Cape Town's Archbishop Dr Thabo Makgoba it was a constant, institutionalised reminder that he was treated differently for being black.

"Founders Day was merely for me an entrenchment of being less than human," he told the BBC.

But Dr Makgoba added that he recognised the power of such occasions.

"If Founders Day was so powerful that it enabled the government to have policies and laws that made racism legitimate, I believe that a day when we celebrate the opposite of that can have the same input," said the archbishop.

Among his other roles, Dr Makgoba is a patron of South Africa Day. The initiative aims to boost economic equality and national pride among all races, and to regenerate areas of the country through voluntary community work.

It also encourages community events on South Africa Day itself (the last Saturday of November), and is working towards the construction of new schools and community centres.

"The main thing is to change the attitude," said Dr Makgoba. "Both black and white need to come to the table and say: 'What has been hurtful about our past, what is hurtful now, and how do we shape the future together?'"

- Published23 August 2017

- Published3 June 2019

- Published7 March 2019

- Published15 March 2017

- Published22 November 2018

- Published26 January 2018

- Published25 January 2018

- Published3 June 2019

- Published4 June 2015