Noor Hossain and the image that helped bring down a dictator

- Published

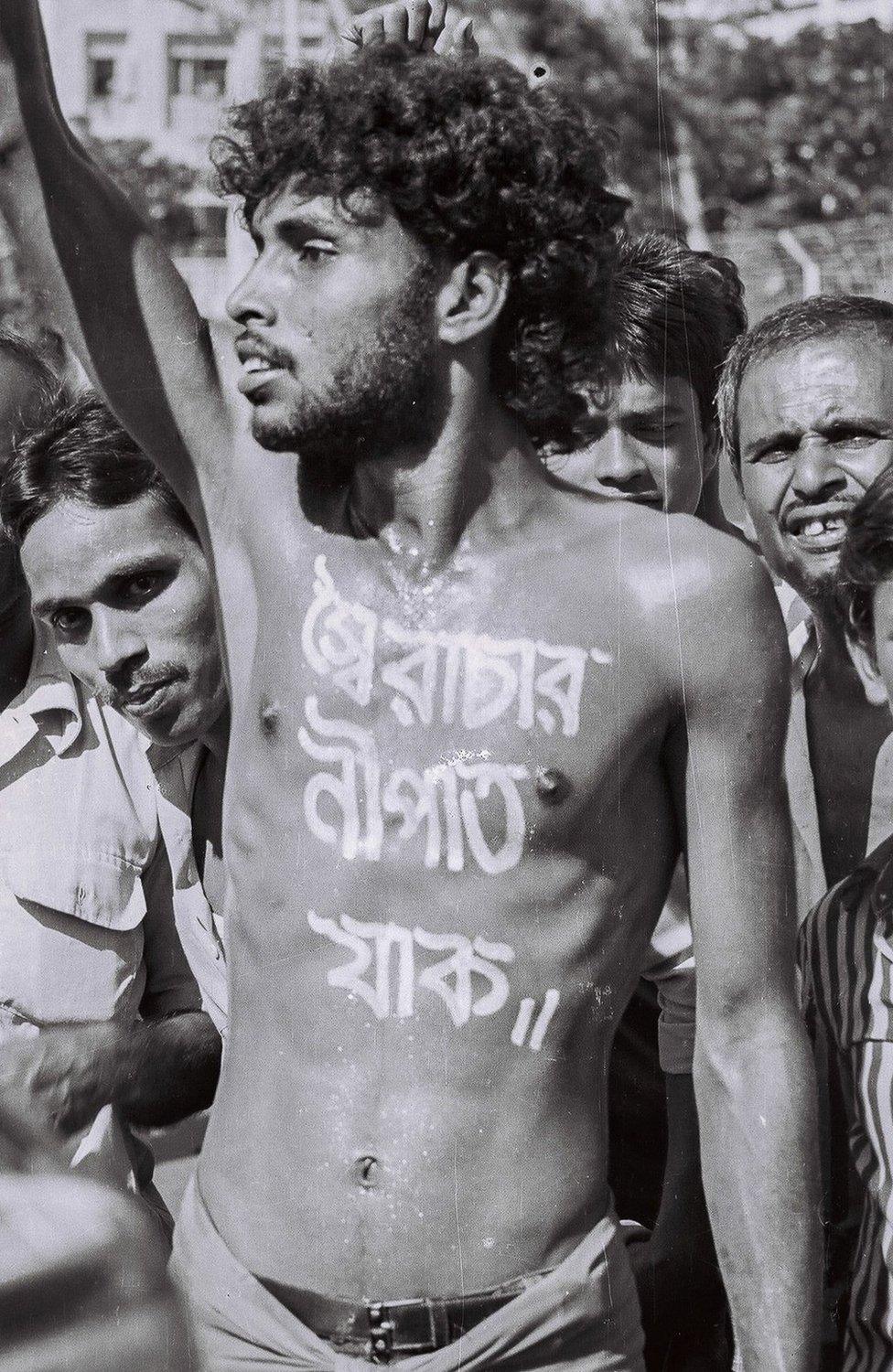

Noor Hossain in Dhaka in 1987, moments before he was shot dead by police

In 1987, a young protester with pro-democracy slogans painted on his body was shot dead by police in Dhaka, Bangladesh. His bullet-ridden body was dumped in a police cell, but a photograph of him helped inspire an uprising that toppled a dictator. The BBC's Moazzem Hossain, who was in the cell next to the painted man's body that day, went in search of the story behind an image.

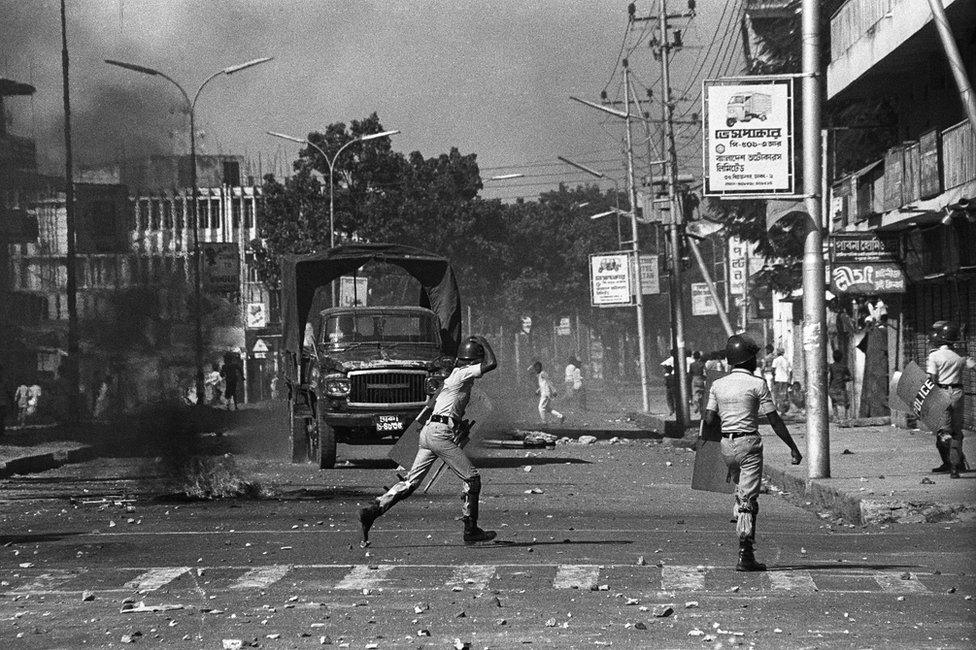

In the week leading up to 10 November 1987, the city of Dhaka was tense. President Hussain Muhammad Ershad had cut off the Bangladeshi capital from the rest of the country, severing virtually all communication channels. Schools, colleges, and universities had been shut and students ordered to vacate halls. Political protests and rallies had been banned, and Ershad, a military dictator, was using emergency powers to detain hundreds of pro-democracy activists.

But opposition political forces were mobilising thousands of supporters to press for the president's resignation. On the morning of 10 November, I was among the thousands of activists heading for the protest. We never made it. At about 9am, me and several other protesters were picked up by riot police. We were beaten mercilessly, bundled into a lorry and taken to the police station.

As the day wore on, more political prisoners were brought in. There were running battles all over Dhaka. Some of the protesters brought in had bullet wounds. Among the bodies one stood out - it had a slogan painted on the bare chest. The words, in bright white paint against the man's lifeless brown skin, electrified us.

"Sairachar nipat jak" - "Down with autocracy".

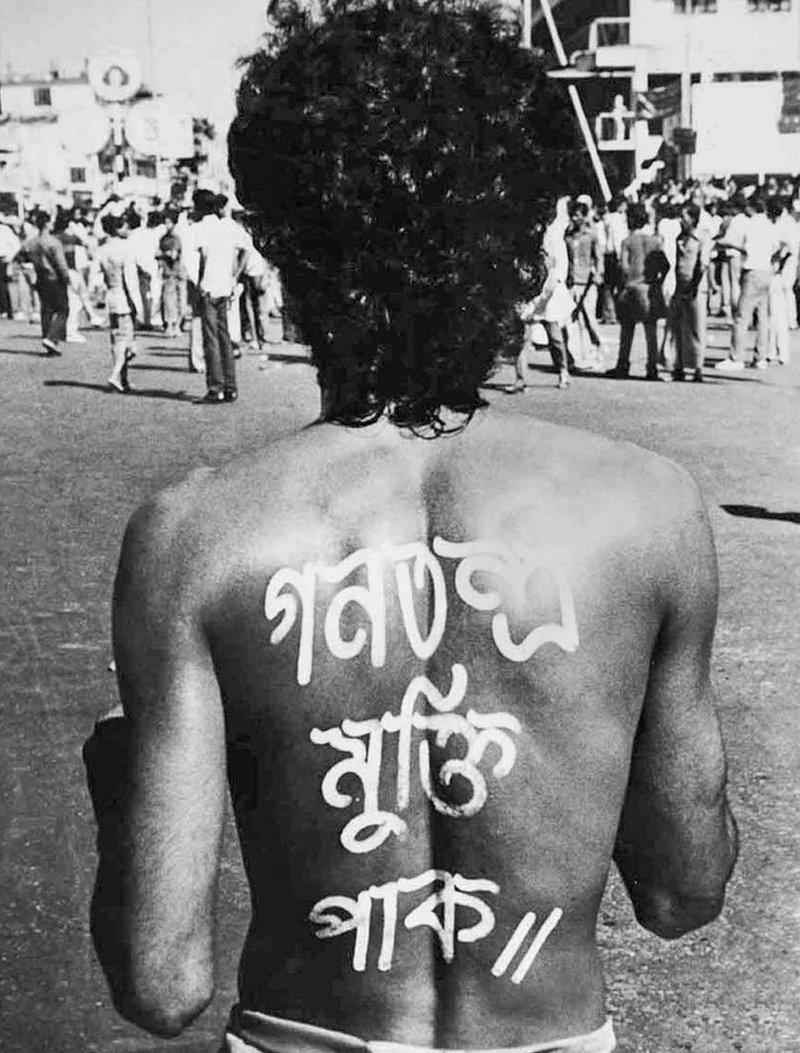

Photographer Pavel Rahman said his heart pounded when he saw Noor Hossain's back

The body belonged to a man named Noor Hossain. We didn't know who he was then. We didn't know that the spot where he was gunned down would be named after him. We didn't know he would go on to become famous - his sacrifice immortalised in books and films, in poems and on postage stamps. We didn't know that a photograph of him taken moments before he died would become a symbol of our generation's long and bloody struggle for democracy.

The brother

I have looked at the photographs of Noor Hossain many times over the past 33 years. He looks determined. His youthful body, and the slogans painted on it, seem to radiate light in the glare of the sun.

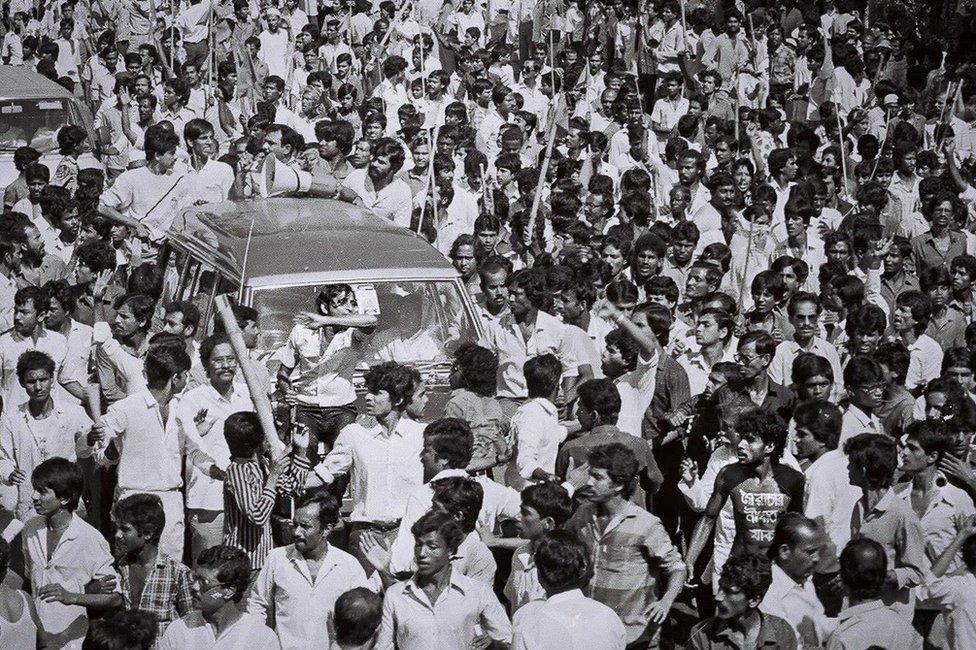

The day after Noor died, aged 26, pictures of him appeared on the front pages of newspapers around Bangladesh, shocking the government and inspiring millions. The protests he and I were involved in in 1987 were violently put down, but three years later another protest movement succeeded in toppling President Ershad, and many of those protesters were inspired by the image of Noor Hossain.

I have often wondered what led this man from a working-class family in Dhaka to commit his extraordinary act. Ahead of the 30th anniversary of the uprising he inspired, I set out to find answers.

Noor's father, Mujibur Rahman, was an autorickshaw driver in the old part of Dhaka at the time. Mujibur died 15 years ago, but I was able to track down Noor's brother Ali. He still vividly remembered the last days of Noor's life.

"My father knew that Noor had been involved in politics - he had frequently stayed away from home and he was taking part in political rallies," Ali said.

Ali Hossain and his father searched Dhaka for his brother's body

After Noor failed to return home for two consecutive nights, his parents became worried. On the morning of 10 November 1987, they tracked him down to a mosque in the city.

"My parents requested him to come back home, but he declined. He said he would come later," Ali recalled. "That was the last time my parents saw him."

Later that day, Noor joined the ranks of protesters. The demonstration turned violent, with protesters throwing bricks and homemade bombs at police and police firing tear gas and eventually live bullets at protesters. Three people, including Noor Hossain, were fatally shot, dozens more were wounded.

Word reached Noor's family home later that day that he had been shot. Mujibur and Ali rushed first to the place Noor had been protesting, then to a police hospital, finally to the station where they heard Noor's body had been taken. The officers outside would not let them in, but they confirmed there was a body inside daubed with paint. If we give you that body now there will be riots, they said.

No officers were ever charged with Noor's murder. No officers were charged during all of Gen Ershad's time in power, despite hundreds of protesters being killed by police.

I asked Ali if he could remember who painted the fateful slogans on his brother's body that day. He said yes, the man's name was Ikram Hossain. Remarkably, Ikram was living at the time in President Ershad's staff quarters, and his brother was the president's messenger. Ali gave me Ikram's number.

The painter

I called Ikram.

"It was me," he said.

In 1987, Ikram was an 18-year-old signboard artist. He lived with his elder brother at Bangabhaban, the presidential residence in Dhaka, and ran a small shop in the Motijheel area, mainly painting signboards and making banners.

"I knew Noor Hossain by face, he used to work as an employee in a business selling used office furniture. But we didn't talk much," Ikram said.

Ikram Hossain painted on Noor. "I told him I can't do this. My brother is the president's messenger," he said

On 9 November, Ikram was finishing his work for the day and planning to shutter the shop by 5pm. But before he could close up, Noor Hossain approached him with a request.

"He took me into a narrow alley nearby. There he wrote the slogans on the wall with chalk. Then he took off his shirt and requested me to write the slogans on his body."

Ikram was scared.

"I told him I can't do this. My brother is the president's messenger. We will be in trouble. You could be arrested. You could be killed."

But Noor was determined. He told Ikram not to worry, that the next day there would be a hundred people with the same slogans painted on their skin.

Police opened fire at stone-throwing protesters during the demonstration in 1987

Ikram relented and painted two slogans on Noor.

"Sairachar nipat jak" ("Down with autocracy") - on his front.

"Gonotontra mukti pak" ("Let democracy be freed") - on his back.

Then Ikram added two full stops after each. "So that I could recognise my writing from the hundred others," he said.

But the next day, there was only one man on the street with painted slogans on his body, and in the moments before he died the bright lettering caught the eye of the photographers in the crowd.

The photographers

Pavel Rahman only ever saw Noor Hossain from the back, he told me. I used to work with Rahman at a newspaper in Dhaka - he has been a photographer for nearly half a century.

When he saw the flash of white paint that day and deciphered the slogan, his heart pounded.

"I had never seen a protester with slogans written on his own body before that," he said. "He immediately captured my attention. Before he disappeared in the crowd, I had the chance to click only twice, one vertical and one horizontal snap, both from the back. I was unaware that he had a slogan written on his chest as well."

That evening, as Rahman was developing the films in the dark room of his newspaper office, a colleague told him that the painted protester had died.

"There was some debate whether we should publish the photo. My editor initially thought it will be too risky, there could be a huge backlash from the government. In the end we decided to go with it," he said.

"President Ershad was furious. There was a suggestion from the government that we faked it. I was scared. I had to go into hiding for several days."

Noor Hossain in the crowd. bottom right, moments before he died.

Pavel's photograph spread round the country and became a poster. But nobody would have known Noor's face if it weren't for another photographer, Dinu Alam, who captured his image from the front.

"I took several shots, all from the front. I was lingering around him for some time, fully unaware that he had another slogan on the back," Dinu said.

The two photographers had between them captured the full extent of Noor's painted protest, and the end of his life.

"Probably I captured the last moments of Noor Hossain," Dinu said.

The night guard

When Ikram Hossain saw the picture on the front page of the newspaper the next day he was devastated. He immediately blamed himself for his friend's death.

"I thought that if I didn't write the slogans on his body, he would be alive," he said.

Fearing for his safety, Ikram went into hiding and avoided police and authorities for several years.

Only after the fall of President Ershad, three years later, did Ikram feel safe. Finally a memorial had been arranged at the site of Noor's grave and Ikram went. After the service, he approached Noor's brother, Ali. Guilt and fear had kept him from the family for years, but now he wanted to tell his story. You should meet my father, Ali said.

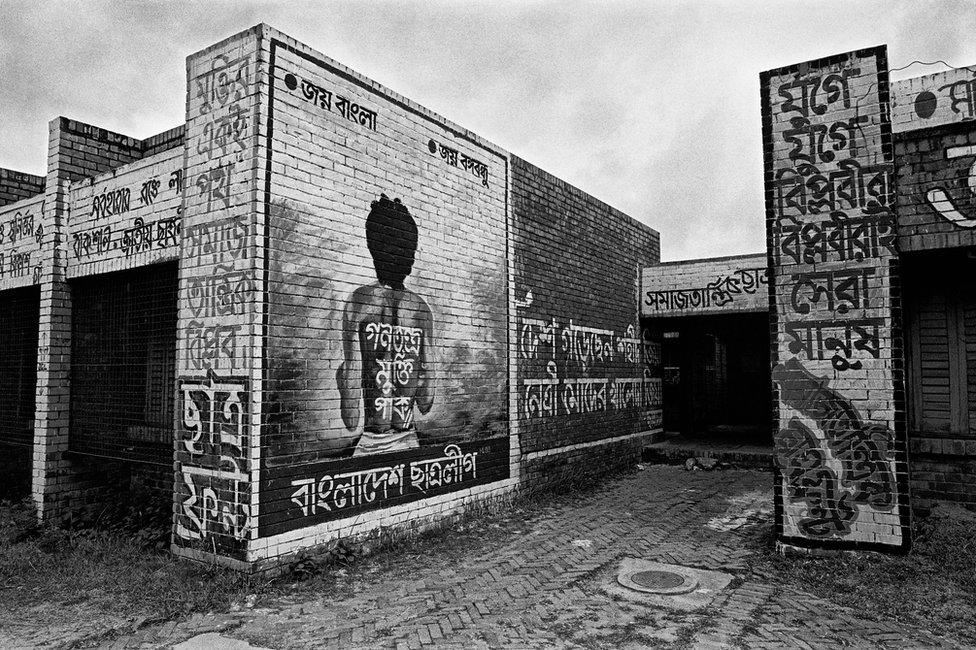

The police control room where Noor Hossain's body was dumped

At the family home, Ikram wept. He apologised and stated his guilt. But Noor's father embraced him. "You are like my son," he said. "We lost Noor Hossain but you are my son now. It is because of you and Noor Hossain that we have democracy."

Back in 1987, it took a week for Mujibur and his wife Mariam Bibi to find out what had happened to their son's body. Noor had been buried by police in secret, in an unmarked grave in a cemetery in Dhaka, alongside two other protesters who were killed that day. But word got to the family via the men who had been made to prepare the bodies and bury them.

I called the caretaker of the Jurain graveyard, where Noor was buried. The caretaker had only been there a few years but he gave me the name of Mohammad Alamgir, who was the night guard at Jurain back in 1987. After a few phone calls, I reached him, and asked him if he remembered that night.

"It was about 2.30am when they arrived," Alamgir said. "I was the night guard but I had to do other things - digging graves, washing bodies, burying the dead."

Alamgir told the men who came that night that he did not bury the dead after 11pm. But they insisted, saying they were from the government. Alamgir took the bodies and began to wash them while others dug the graves.

"The body with the writings on had a bullet hole below the chest, near the belly," he said. "I tried to scrub off the paint, but it was too difficult."

He said the same to Ikram Hossain, the painter, back in 1990 when the two met at the graveside. "It must have been difficult," Ikram replied. "I wrote the slogans in enamel paint."

A mural of Noor Hossain painted at a university campus in Dhaka in 1990.

Much later, Noor's parents received another surprise visit from someone who had waited years to see them. In 1997, General Ershad, who had been sent to prison in 1990, was released, and he visited Mujibur and Mariam at their home. He had come to apologise.

"He said to my father, 'If your son was alive today, the way he would have taken care of you, I will try to do the same'", Ali Hossain recalled.

Over the next few years, Ershad kept in touch and occasionally sent the family money, until Mujibar spoke at a memorial for his son at Dhaka University one day, telling the audience, "I never want to see the return of dictatorship in Bangladesh."

It infuriated Ershad, Ali said.

"He never called my father again."

The general

I met General Ershad once, more than a decade after Noor died. It was 1999 and Ershad, then an opposition politician, was travelling up and down the country to rejuvenate his support base. I accompanied him on a river trip in southern Bangladesh. One of his aides had told him that I was a radical activist during my student days and had been jailed by police.

"I hear you were a revolutionary," he said jokingly one day during breakfast.

General Ershad took power in Bangladesh in Dhaka in a coup in 1982

The general, who died last year, had an easy-going, charming personality, but he had many faces. He came to power in a bloodless military coup in 1982, following the same script used by military rulers all over the world - pledging to fight corruption, reform the government and clean up politics. He made Islam the state religion of Bangladesh, fundamentally changing the secular constitution, to please religious conservatives.

His electoral victory in 1986 was marred by charges of voter fraud, and while in office Ershad suspended the country's constitution and parliament and cracked down on political opponents. And he presided over the violent putting down of the 1987 protests that landed me in a prison cell and cost Noor Hossain his life.

General Ershad was also vain. He had his poems - rumoured to be written by ghostwriters - published on the front page of national newspapers, while heavily censoring the papers' news reports.

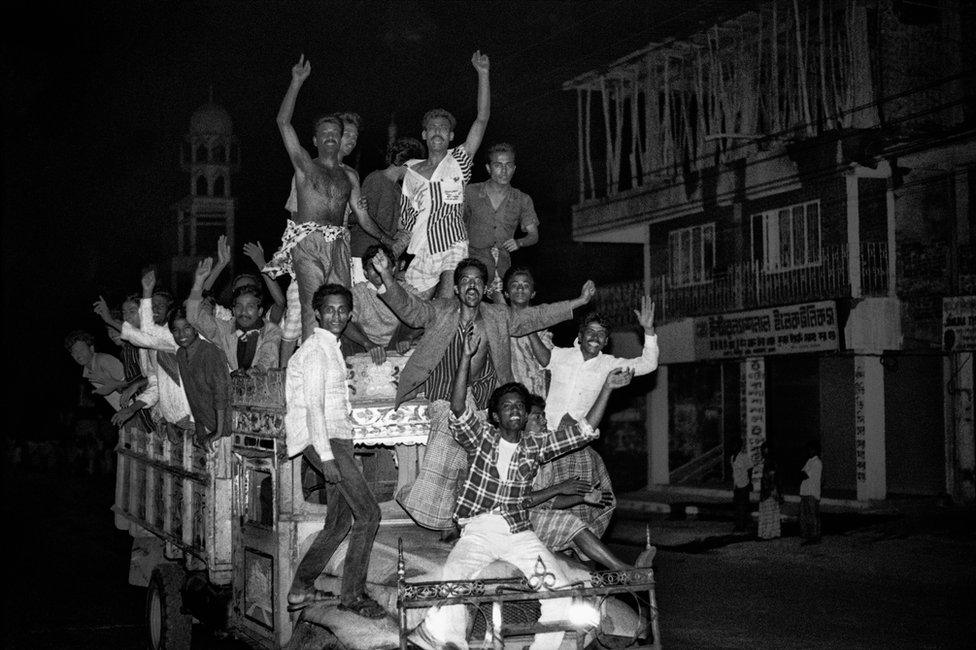

People cheering on a the back of a vehicle in Dhaka after the success of the 1990 uprising

Ershad's nine-year rule came to an end in 1990, when he was forced to resign in the face of a mass uprising. Days later he was imprisoned. Thousands of people were marching, singing, dancing on the streets of Dhaka. I can still remember the jubilation of that day. The country had not seen anything like it since independence in 1971. It felt like a new dawn, a fresh start for Bangladesh. But it was short lived.

The two main parties, the Awami League and the BNP, were soon locked in a bitter fight for power. In the coming decades they took turns to rule the country, deploying the very same authoritarian tactics used by the old regime.

Bangladesh's descent back into authoritarianism pains the activists who suffered in their long fight for freedom against General Ershad.

"We sacrificed our youth, the best part of our life, to fight for democracy," said Nasir-ud-doza, a veteran of the 1990 uprising who I first met in a police lorry in 1987, where he was being kicked repeatedly as the lorry rumbled along the road to the station.

"I will never be able to forgive those politicians who killed our dream for their petty personal or party interests," he said.

After Ershad fell, the spot where Noor Hossain was killed was renamed Noor Hossain Square

Bangladesh had briefly enjoyed democracy "in its full flourish", Ikram Hossain recalled, "like a bright full moon in the night sky".

"Where is that democracy now?" he said.

Ikram is still a signboard artist, though the work is mostly digital now. There is little need to have enamel paint lying around. His small shop on Hatkola Road is just a few hundred metres from the presidential staff quarters where he lived in 1987. A little further away, near Ikram's old shop, is the alley where he wrote the slogans on Noor's body, and a little beyond that the spot where Noor was gunned down, now called "Noor Hossain Square".

Ikram can still clearly remember daubing the thick paint on Noor Hossain that day, his hands shaking with fear.

"It was not my best handwriting," he said. "But it was the best thing I have ever written."

Photographs by Yousuf Tushar for the BBC

Related topics

- Published15 August 2018