Shukatsu sexism: The Japanese jobseekers fighting discrimination

- Published

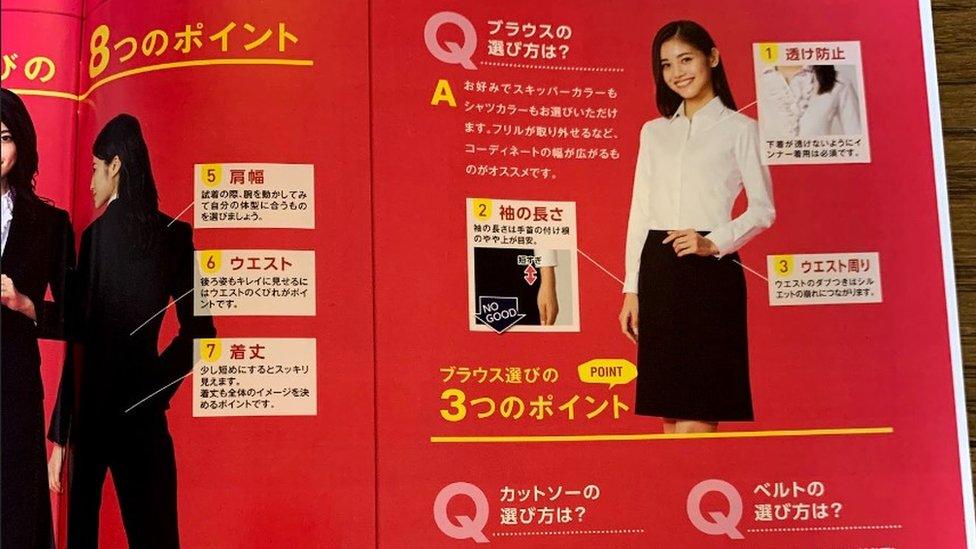

The rigid dresscode leaves little choice

Japan has one of the most intense, fiercely competitive and stressful recruitment processes for new graduates anywhere in the world. The way men and women are expected to dress is just one of the many demands part of the highly rigid experience. But as a few raise their voices against the system, things may be slowly changing.

"I'm not cisgender but also not transgender at the same time. I don't want to be identified as a man or woman, just me, myself," says Yumi Mizuno, an interpreter in her early 30s.

When speaking English she uses feminine pronouns, but Ms Mizuno identifies as non-binary, an umbrella term that refers to people who do not see their gender as being exclusively male or female. In Japanese she prefers the gender-neutral "jibun", meaning "myself".

Back in 2011 she was one of thousands of student job hunters, dressed in black and taking part in Japan's highly-structured, year-long recruitment process known as "Shushoku katsudo", or "Shukatsu" for short.

Applicants are expected to wear what are known as 'recruit suits' that come in two varieties: a men's suit, worn with a white shirt and dark tie, and a women's suit with a skirt, white blouse and a jacket that's cinched in at the waist.

But for Ms Mizuno, that gender-based choice is unacceptable so she's raising her voice to challenge a system that dates back to the 1950s.

High stakes

Competition is intense, which has spurred the growth of an entire industry devoted to grooming students for success during the Shukatsu period.

Recruiters and clothing companies provide detailed guidelines that define things like the recruit suits students can wear, the haircuts they can have and even how they should sit during an interview.

Ms Mizuno says she doesn't fit into the gender binary

"They only provide etiquette and clothing instructions based on a gender binary, for men and women," she says, "and I felt I couldn't fit in either of them.

"It's very scary, because in Japan we're taught to get a job before we graduate from university."

Shukatsu begins every April and culminates in a hiring season that lasts from August to October. Those who miss out on a job offer risk having to wait and repeat the process the next year, competing against a fresh crop of students.

It's a prospect that, historically, has come with a degree of shame attached.

"The stigma can damage their chance of gaining a quality graduate position in the following year," explains Dr Kumiko Kawashima, an expert in Japan's working culture at Macquarie University in Australia.

"Given this reality, it is not unheard of that professors allow final year students to concentrate on job hunting instead of turning up to class," she says.

Dropping out

A low point for Ms Mizuno came when she went to a job interview dressed in flat shoes, a suit jacket, trousers and tie - the typical uniform of a male job hunter.

"It was very scary, I felt I couldn't take the risk. I went to the station bathroom and I took off my tie, put on makeup, changed my shoes from flats to high heels," she says.

"Even after I changed my clothes at the station, I was still afraid because I had a bag that's for boys. I was scared, what if the interviewers judge me for having the wrong bag?"

Not long afterwards, she dropped out of the Shukatsu process.

"I thought, 'I'm losing my identity'," she says, "so I started to cover myself up. I couldn't go out at that time. I locked myself up in my apartment for three months."

Dr Kawashima says she's not surprised by that story.

"In the name of etiquette, Shukatsu 'experts' teach a rigid gender performance where being masculine is the opposite of being feminine and nothing in between or outside of the binary exists," she tells the BBC.

"Students have little choice but to conform to those styles so as not to jeopardise their chances of landing a good job."

'Anyone can speak up'

There are signs that Japan is warming up to diversity, however.

A recent survey by the Kyodo news agency, external found that over 600 schools across Japan had relaxed their rules on gender-segregated uniforms, allowing students to dress according to their gender identity. In October Japan Airlines stopped calling passengers "ladies and gentlemen" during English-language announcements, choosing to go with the gender-neutral "all passengers" and "everyone" instead.

In a case that made headlines around the world in 2019, the actress Yumi Ishikawa started an online movement called #KuToo (a play on #MeToo and the Japanese word for shoes, "kutsu") after she was forced to wear high heels every day while working at a funeral home.

"I hope this campaign will change the social norm so that it won't be considered to be bad manners when women wear flat shoes like men," Ms Ishikawa told reporters at the time.

As the #KuToo campaign gained international attention, Yumi Mizuno began to work as an interpreter for Ms Ishikawa, translating for her during media interviews in English.

Yumi Ishikawa started the #KuToo movement

Inspired by #KuToo's impact, Ms Mizuno asked a group of like-minded people to help start a campaign called Stop #ShukatsuSexism. The campaign calls on recruiters and clothing companies to accommodate a more diverse range of people with their products.

"Just one sentence on their instructions or below their instructions could change society. Like, for example, saying 'this is just a guideline, you can choose other suits, as well'," she says.

"I don't want them to change everything at the same time, but I want them to try and show their effort."

'We don't have people like you'

Kento Hoshi understands what it's like to be different. A victim of discrimination himself, the 26-year-old was bullied out of school for being gay when he was 14.

But it was a transgender friend's Shukatsu experience that inspired him to try to change the way Japanese recruitment works.

"One company wrote about diversity and inclusion activities, so she thought it would be ok for her," he says.

But when she mentioned that she was transgender during her job interview, she was asked to leave.

"The interviewer said, 'We don't have people like you'," Mr Hoshi says.

Yumi Mizuno pushed her cause at the Tokyo pride event

He decided to set up a website where people could share their experiences of job interviews at various companies. That website later grew into Japan's first recruitment agency aimed at LGBT people, Job Rainbow.

"If diverse people, including LGBT, can't work, it has a really bad effect on the Japanese economy. I want to make it a win-win relationship," he says.

Companies forced to change

This debate isn't unique to Japan. In the UK alone, moves toward accommodating a wider variety of gender identities has led to conflict over toilets, school uniforms and passports.

"While Japan's case seems extreme due to the institutionalised and uniform nature of the Shukatsu process, similar gender biases abound in the business world elsewhere," says Macquarie University's Dr Kawashima.

But it remains the case that the country's low birth rate and strict limits on immigration have left businesses competing for an ever-shrinking pool of fresh recruits, sparking a burst of change.

In 2018, Keidanren, the federation representing many of Japan's largest companies, announced that by March 2021 the Shukatsu system would no longer run on a strict annual timetable, a move that aims to help Japanese firms compete against foreign recruiters. There have not, however, been any official moves to encourage the availability of more diverse clothing options.

"Japan's shrinking and ageing population is making the search for young talent more competitive," says Dr Kawashima.

"Embracing and promoting diversity during and beyond recruitment will be increasingly important if employers want to remain relevant in the eyes of capable job seekers."

Kento Hoshi agrees. "We get a lot of enquiries from many huge companies who want to be more LGBT-friendly. I feel like society is changing."

Yumi Mizuno's own push for change has gathered over 13,000 signatures in support of its call for companies to recognise a greater diversity of clothing options. She hopes it will benefit every job seeker.

"The campaign is not only for LGBT+ people, because what's wrong is this gender binary," she says.

"I want them to present all types of suits equally for each gender. Then the people like me, trans people, queer people won't think they're wrong, that they're marginalised."

Related topics

- Published8 November 2019

- Published5 June 2019

- Published6 March 2019