Covid-19: Sri Lanka forcibly cremates Muslim baby sparking anger

- Published

Sri Lanka's Muslim minority are fighting to change the Covid-19 cremation rules

The forced cremation of a 20-day-old Muslim baby in Sri Lanka has highlighted the government's controversial order to burn the bodies of all those who died of Covid. Critics say the decision is not based in science and only intended to target the minority community. BBC Sinhala's Saroj Pathirana reports.

Mohamed Fahim and his wife Fathima Shafna were thrilled when their baby boy Shaykh was born on 18 November after a six-year wait.

But their joy was short-lived.

On the night of 7 December, they noticed the baby was struggling to breathe. They rushed him to the capital Colombo's best children's hospital, the Lady Ridgeway.

"They told us the baby was in a severe condition and was suffering from pneumonia. But then, around midnight, they did an antigen test and told us the baby was positive for coronavirus," Mohamed Fahim, who drives a three-wheeler for a living, told BBC Sinhala.

Doctors then tested Mr Fahim and his wife but they were both negative.

"I asked how my baby was positive when both of us, even the mother who was breastfeeding him, were negative?"

Despite tears and pleas, the anxious couple were sent home by officials who said more tests were needed. They were told to call the hospital for updates.

The next day, they were informed that their baby had died of Covid. Mr Fahim repeatedly asked doctors to conduct a PCR test to reconfirm this, but they refused.

Then, doctors asked him to sign a document authorising the cremation of their child, as required by law in Sri Lanka.

Mr Fahim refused: the cremation of bodies is forbidden in Islam, considered a form of mutilation, forbidden by Allah.

And he is not alone. Some Muslim families have refused to claim the bodies of their dead, leaving the government to cremate them on state expense, while many will not accept the ashes of their loved ones.

Sri Lankans of all faiths tied ribbons outside the cemetery where Shaykh was cremated

Mr Fahim says he repeatedly asked for his baby's body to be handed back to him, but officials said no. The next day, he was told his son's body was being taken to the crematorium.

"I went there but I didn't enter the hall," he says. "How can you watch your baby son being burnt?"

'No evidence'

Political, religious and community leaders representing the Muslim community have repeatedly requested the government to change its "cremate only" policy, pointing to the more than 190 countries allowing burials, and World Health Organization advice. It has even taken its fight to the Supreme Court, but the cases were dismissed without an explanation.

The government argues burials could contaminate ground water, based on the say-so of an expert committee, the composition and qualifications of which are unknown.

World-renowned virologist Prof Malik Peiris, however, has questioned the theory.

"Covid-19 is not a waterborne disease," Prof Peiris told the BBC. "And I haven't seen any evidence to suggest it spreads through dead bodies. A virus can only multiply in a living cell. Once a person dies, the ability of the viruses to multiply decreases."

He added: "Dead bodies aren't buried right in running water. Once you bury the body six feet under wrapped in impermeable wrapping, it is highly unlikely it would contaminate running water."

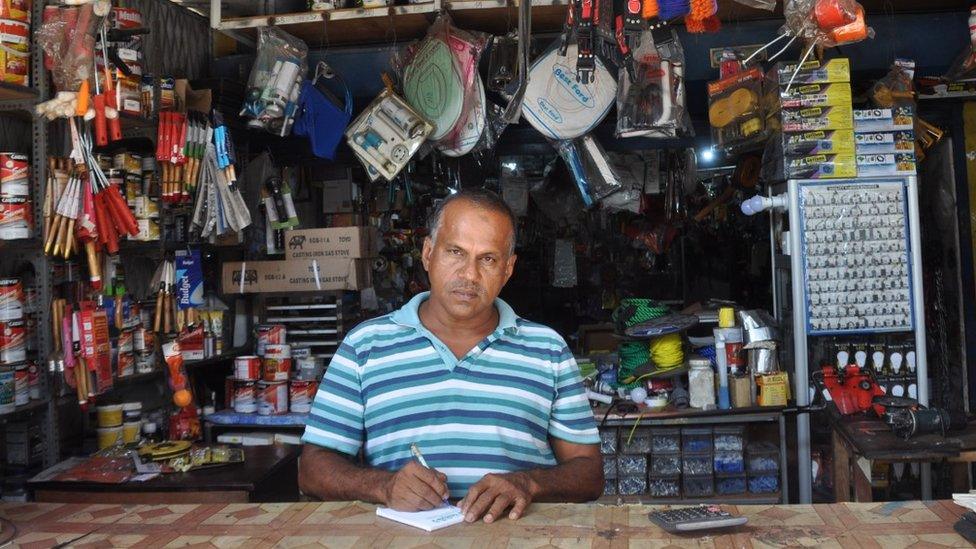

Muslim groups have filed court petitions to change the cremation rule

There had not been much sympathy for the plight of the Muslim community - but the forced cremation of baby Shaykh has changed that.

Soon after the news broke, men, women, clergy from other faiths, rights activists and opposition politicians gathered outside the crematorium, and tied white ribbons on the gate. Many were from the majority Sinhala community.

People have also taken to social media to condemn what happened.

Activist and lawyer Thyagi Ruwanpathirana, who was among those who tied white cloth on the gate, tweeted about her experience: "While I was tying it, a mother and daughter duo crossed the road and joined me with their own white cloths. Till I came they were worried someone may be watching.

"I couldn't quite make out what the mother was trying to say at first because we all had our masks on. Then she said, 'The baby was only two-days-old no? Sin. This way at least my heart will be satisfied'."

The white cloths disappeared overnight, believed to have been removed by authorities, but the anger did not.

The white cloths which adorned the gates disappeared overnight

Hilmy Ahmed, the vice-president of the Muslim Council of Sri Lanka, told the BBC it was clear this was all part of a "racist" agenda, targeting the Muslim minority.

"The government doesn't seem to be responding to anything based on science," he said. "They don't seem to take into consideration the advice of virologists or microbiologists or epidemiologists. This is racist agenda of a few in the technical committee."

"This is probably the last straw for Muslims because nobody expected this little baby to be cremated," he added. "That also without even showing the child to the parents."

But the government denies that the measures are aimed at Muslims, pointing to the fact Sinhala Buddhists are having to cremate their loved ones within 24 hours, which also goes against their traditions.

"Sometimes we will have to do things that we don't like too much," the cabinet spokesman, Minister Keheliya Rambukwella, told the BBC.

"Everybody has to make some kind of sacrifices during this Covid pandemic. I understand this is a very sensitive issue. Even my Muslim friends are calling me and asking me to help them. But as a government we have to take the decisions based on science for the sake of all concerned."

The government says it is looking for suitable land to bury Muslim Covid-19 fatalities

Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa has, meanwhile, instructed authorities to find a suitable dry land to bury those dying from coronavirus, his office said in a statement.

Mannar in northern Sri Lanka is thought to be considered by the authorities as a possible location. But it is not being seen as viable by the Muslim community - many of them were driven out of there by Tamil separatists in 1990. They fear that burials there will cause more tension.

And Mr Ahmed has dismissed the offer as "a carrot they are holding every time the pressure" increases. After all, the prime minister has issued similar instructions before, but Muslims are still being cremated.

Meanwhile, Mr Fahil says he still can't come to terms with what happened to his baby son, Shaykh.

"My only wish is that no other person should go through this pain. I don't wish any other child to experience what happened to my son."

Update 8 December 2021: This article was amended to reflect correct teaching on cremation and resurrection.

Related topics

- Published5 July 2020

- Published13 August 2019