Covid: How the war on the virus attacked freedom in Asia

- Published

Safoora Zargar was arrested in April

Safoora Zargar was more than three months pregnant when she was arrested in the Indian capital Delhi for participating in a protest against a controversial citizenship law.

It was 10 April, and the pandemic was just beginning to take root in India.

The government's own advice said pregnant women were particularly vulnerable to infection, but for more than two months she was held in the overcrowded Tihar jail.

"They'd tell other prisoners not to talk to me. They'd told them I was a terrorist who'd killed Hindus. Now these people didn't know about the protests, they didn't know I was jailed for participating in a protest," she told the BBC's Geeta Pandey in Delhi after her release.

Her crime had been taking part in widespread protests against the law which critics say targets the Muslim community. The demonstrations had captured the imagination of the country and attracted global attention.

But there were no protests in the street demanding her release. There couldn't be: India was under one of the world's strictest lockdowns, with people confined to their homes. Her arrest was one of many which took place during this time.

And it was not just India. Activists say numerous governments across Asia used the cloak of coronavirus to implement laws, carry out arrests, or push through controversial schemes which otherwise would have sparked a backlash, both at home and abroad.

A controversial citizenship law saw thousands march in protest

But instead of a backlash, many governments have seen their popularity increase as people turned to them for direction during the crisis.

"The virus is the enemy and people are put on a war footing. This allows governments to pass oppressive laws in the name of 'battling' the pandemic," Josef Benedict of Civicus, a global alliance of civil society organisations and activists, told the BBC.

"This has meant that human and civic rights have taken a step back."

Indeed, Civicus's latest report, "Attack on people power", says the Asia Pacific region has seen "attempts by numerous governments to stifle dissent by censoring reports of state abuses, including in relation to their handling of the pandemic".

It cites increased surveillance and tracking - currently used for contact tracing - as well as the imposition of strict laws intended to stifle any criticism as some of the ways in which this happens. Given that many of these measures are introduced as a response to the pandemic, there is little to no resistance against them.

The Civicus report states that at least 26 countries in the region have seen harsh legislation, while another 16 have seen human rights defenders prosecuted.

'A chilling message'

In India, apart from Safoora, other human rights defenders and activists - including a 83-year-old Jesuit priest with Parkinsons - have been charged and arrested with sedition, criminal defamation and under anti-terrorism laws which make it nearly impossible to get bail.

The situation has prompted several organisations to raise an alarm. Five UN special rapporteurs expressed concern saying the arrests seemed "clearly designed to send a chilling message to India's vibrant civil society".

Maitreyi Gupta, legal advisor India for the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), told the BBC that they had consistently called on the government to release political prisoners.

However, despite international pressure, arrests have continued unabated, and to little protest.

The government has consistently maintained that those they have arrested have been acting against the interests of the country and denied charges that they were engaging in a witch hunt.

In the Philippines, the arrest of 62-year-old activist Teresita Naul - who has a known heart condition and asthma - on charges of kidnapping, serious illegal detention, and destructive arson led to an outcry.

But Naul, who was paraded in front of the media as a top "Communist leader", was just one of more than 400 people accused of these crimes, largely activists and journalists. Others, like Zara Alvarez and Randall Echanis, have been attacked and killed.

Meanwhile, the forced shutdown of the country's biggest media network ABS-CBN in May also deprived many of access to crucial information during the pandemic.

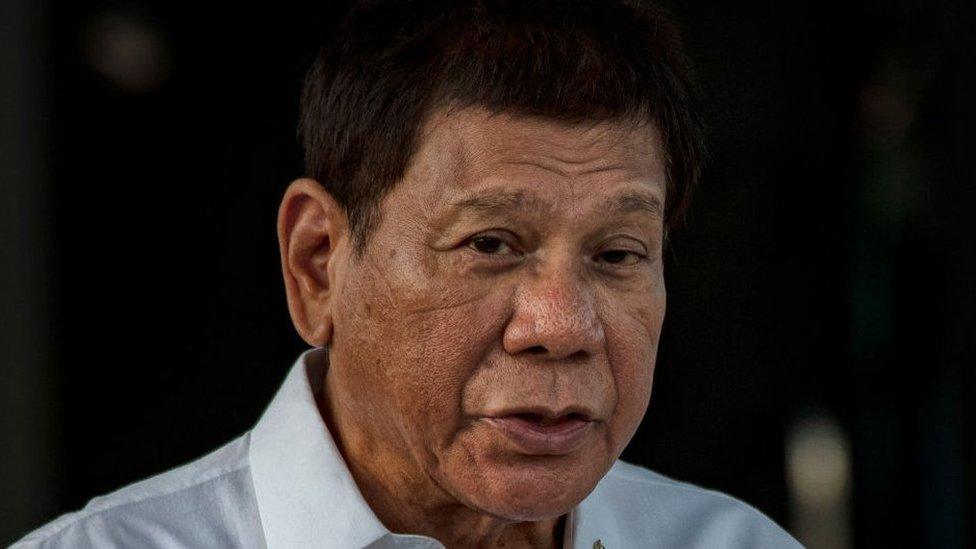

And yet, President Rodrigo Duterte's popularity remains high.

Broadcaster ABS-CBN was forced to shutdown earlier this year

Bangladesh has also shut down several websites critical of the government for spreading "misinformation" on Covid.

And in Nepal, Bidya Shreshta, an activist from the indigenous Newar community, told the BBC that the government has used the pandemic as a means to persecute the group.

During the pandemic, Ms Shreshta says, officials violated a Supreme Court order and or went ahead with the demolition of 46 houses in the Newar's traditional settlements in the Kathmandu valley, making way for a new road.

Officials ignored protest, some of which were dispersed forcibly. The government says that the locals need to communicate their concerns through "proper channels" and has vowed that the building of the highway will go ahead because it's for the "public good".

The Civicus report also cites Cambodia, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Vietnam as countries of concern as they have all seen the targeting of individuals with disproportionately harsh penalties - many of which were handed down for spreading allegedly false information about the pandemic.

And countries like Myanmar have been criticised for using "terrorism" as an excuse to justify restrictions on freedom of expression.

In Hong Kong, protests between police and protesters grew increasingly violent

Sometimes though, government action is not directly related to the pandemic - but whether it could have happened without it will never be known.

In Hong Kong, the passage of the national security law in June - after the virus virtually ended the almost daily protests seen across the city - has had a chilling effect on its pro-democracy movement.

Other things are definitely related to the pandemic but, on the surface, benign.

The employment of surveillance technologies in countries like South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong, has proved immensely effective in controlling the virus, but the ICJ has expressed concern that they may continue to be used even when the pandemic ends.

Mr Benedict feels that in many of these countries, civil society organisations have stepped up to fill the gaps entered by the government. And he also takes heart that protests are still continuing in many countries such as the anti-monarchy protests in Thailand and the "omnibus" job creation law in Indonesia.

However, the impact of many of the laws passed and arrests made this year are likely to last long after the pandemic is over.

Milk Tea Alliance: The Asian youth activists fighting for democracy

- Published12 March 2024

- Published10 July 2020

- Published12 November 2020

- Published11 March

- Published19 March 2024

- Published21 May 2020

- Published24 March 2020