Why are there protests in Hong Kong? All the context you need

- Published

How Hong Kong got trapped in a cycle of violence

Hong Kong has seen several months of pro-democracy protests - and China appears to be tightening its grip.

The protests began in June 2019 over plans - later put on ice, and finally withdrawn in September - that would have allowed extradition from Hong Kong to mainland China. They then spread to reflect wider demands for democratic reform, and an inquiry into alleged police brutality.

Now, China is proposing to introduce a new national security law, which critics believe could be used to crack down on rights and political activists.

This is not all happening in a vacuum. There's a lot of important context - some of it stretching back decades - that helps explain what is going on.

Hong Kong has a special status...

It's important to remember that Hong Kong is significantly different from other Chinese cities. To understand this, you need to look at its history.

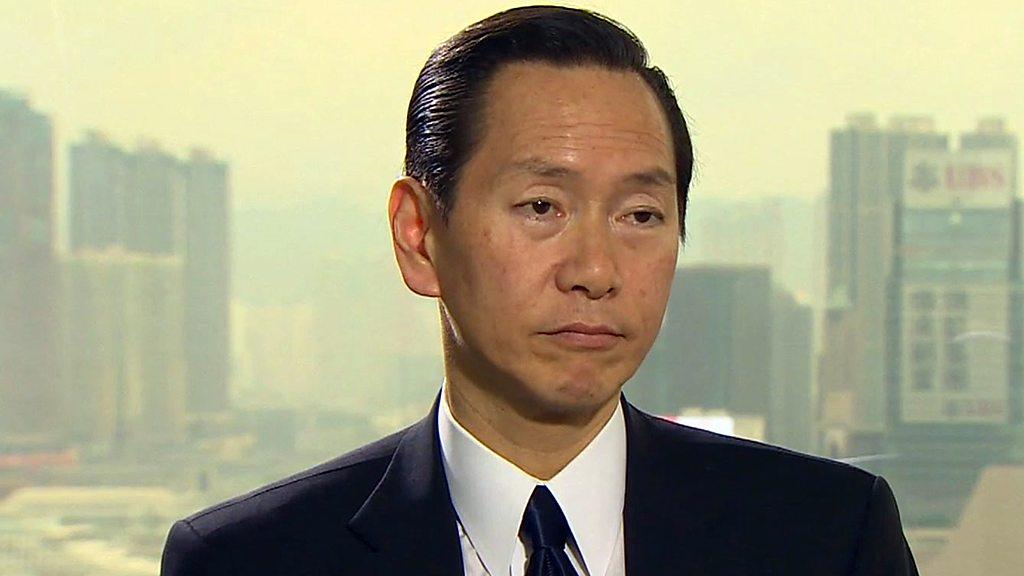

The BBC's Helier Cheung on Hong Kong's 2019 protests

It was a British colony for more than 150 years - part of it, Hong Kong island, was ceded to the UK after a war in 1842. Later, China also leased the rest of Hong Kong - the New Territories - to the British for 99 years.

It became a busy trading port, and its economy took off in the 1950s as it became a manufacturing hub.

The territory was also popular with migrants and dissidents fleeing instability, poverty or persecution in mainland China.

Then, in the early 1980s, as the deadline for the 99-year-lease approached, Britain and China began talks on the future of Hong Kong - with the communist government in China arguing that all of Hong Kong should be returned to Chinese rule.

The two sides signed a treaty in 1984 that would see Hong Kong return to China in 1997, under the principle of "one country, two systems".

This meant that while becoming part of one country with China, Hong Kong would enjoy "a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs" for 50 years.

As a result, Hong Kong has its own legal system and borders, and rights including freedom of assembly, free speech and freedom of the press are protected.

For example, it is one of the few places in Chinese territory where people can commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, where the military opened fire on unarmed protesters in Beijing.

...but things are changing

Hong Kong still enjoys freedoms not seen in mainland China - but they are widely thought to be on the decline.

Rights groups have accused China of meddling in Hong Kong, citing examples such as legal rulings that have disqualified pro-democracy legislators, and the disappearance of five Hong Kong booksellers, and a tycoon - who all eventually re-emerged in custody in China.

There are also accusations that press and academic freedoms have been deteriorating. In March, China effectively expelled several US journalists - but also prohibited them from working in Hong Kong.

The public broadcaster RTHK has come under pressure from Hong Kong's government, first for broadcasting an interview with the World Health Organization about Taiwan, and then for targeting police in its satirical news show "Headliner".

The local examinations body also came under fire for a world history question about relations between Japan and China, with the government demanding the exam question be invalidated. The government said it was a professional, rather than political, decision, but many academics expressed concern.

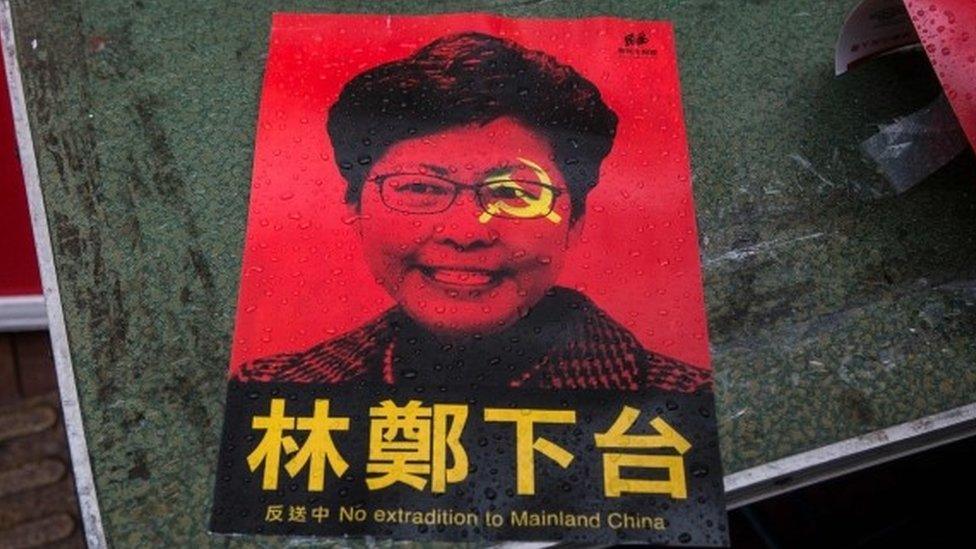

Police use tear gas on protesters

Another sticking point has been democratic reform.

Hong Kong's leader, the chief executive, is currently elected by a 1,200-member election committee - a mostly pro-Beijing body chosen by just 6% of eligible voters.

Not all the 70 members of the territory's lawmaking body, the Legislative Council, are directly chosen by Hong Kong's voters. Most seats not directly elected are occupied by pro-Beijing lawmakers.

Some elected members have even been disbarred after Beijing issued a controversial legal ruling that effectively disqualified them.

Hong Kong's mini-constitution, the Basic Law, external, says that ultimately both the leader, and the Legislative Council, should be elected in a more democratic way - but there's been disagreement over what this should look like.

The Chinese government said in 2014 it would allow voters to choose their leaders from a list approved by a pro-Beijing committee, but critics called this a "sham democracy" and it was voted down in Hong Kong's legislature.

In 28 years' time in 2047, the Basic Law expires - and what happens to Hong Kong's autonomy after that is unclear.

Most people in Hong Kong don't see themselves as Chinese

While most people in Hong Kong are ethnic Chinese, and although Hong Kong is part of China, a majority of people there don't identify as Chinese.

Surveys from the University of Hong Kong show that most people identify themselves as "Hong Kongers", external - only 11% would call themselves "Chinese", external - and 71% of people say they do not feel proud about being Chinese citizens, external.

The difference is particularly pronounced amongst the young.

"The younger the respondents, the less likely they feel proud of becoming a national citizen of China, and also the more negative they are toward the Central Government's policies on Hong Kong," the university's public opinion programme says.

Hong Kongers have described legal, social and cultural differences - and the fact Hong Kong was a separate colony for 150 years - as reasons why they don't identify with their compatriots in mainland China.

There has also been a rise in anti-mainland Chinese sentiment in Hong Kong in recent years, with people complaining about rude tourists disregarding local norms or driving up the cost of living.

Some young activists have even called for Hong Kong's independence from China, something that alarms the Beijing government.

Hong Kongers know how to protest

Demonstrations in 2014 went on for several weeks

There's a rich history of dissent in Hong Kong, stretching back further even than the past few years.

In 1966, demonstrations broke out after the Star Ferry Company decided to increase its fares. The protests escalated into riots, a full curfew was declared and hundreds of troops took to the streets.

Protests have continued since 1997, but now the biggest ones tend to be of a political nature - and bring demonstrators into conflict with mainland China's position.

The BBC's Nick Beake inside the Legislative Council after protests in 2019

While Hong Kongers have a degree of autonomy, they have little liberty in the polls, meaning protests are one of the few ways they can make their opinions heard.

As a result, many see taking to the streets as their only way of forcing change.

And, in the past, some protests have been successful. In 2003, up to 500,000 people took to the streets, external to protest against a controversial security bill the Hong Kong government was trying to pass. The local government also backed down over "patriotic education" classes following rallies against the move.

However, the Chinese government has adopted a harder stance in recent years, particularly with any movements it views as a direct challenge to its own authority.

In 2014, demonstrators took to the streets peacefully for several weeks, demanding Hong Kongers be given the right to elect their own leader. But the so-called Umbrella movement eventually fizzled out with no concessions from Beijing.

How did the latest crisis escalate?

In June 2019, protesters took to the streets again, demonstrating against plans to allow extraditions to mainland China. This time, clashes between police and activists became increasingly violent.

The history behind Hong Kong's identity crisis and protests - first broadcast November 2019

The bill was halted, and later fully withdrawn, but demonstrations continued for months, with demands for full democracy and an independent inquiry into police actions.

In April this year, Hong Kong police arrested 15 of the city's most high-profile pro-democracy activists for taking part in unauthorised assemblies.

In May, Hong Kong's police watchdog said it found no significant wrongdoing on the police's part during the 2019 protests - in a report that was criticised by many rights groups and external experts.

The street protests have mostly died down during the coronavirus pandemic, although some small demonstrations, including singing protesters in shopping malls, have started again as restrictions are gradually eased.

Now, China is proposing to introduce a new national security law in Hong Kong, which could be similar to the one withdrawn in 2003. It says the legislation is "highly necessary" and would "safeguard national security in Hong Kong".

However, the new proposal is also controversial because it is expected to circumvent Hong Kong's own law-making processes - leading to accusations that Beijing is undermining Hong Kong's autonomy.

- Published12 June 2019

- Published10 June 2019

- Published10 June 2019

- Published9 June 2019

- Published13 December 2019

- Published1 April 2019