North Korea enslaved South Korean prisoners of war in coal mines

- Published

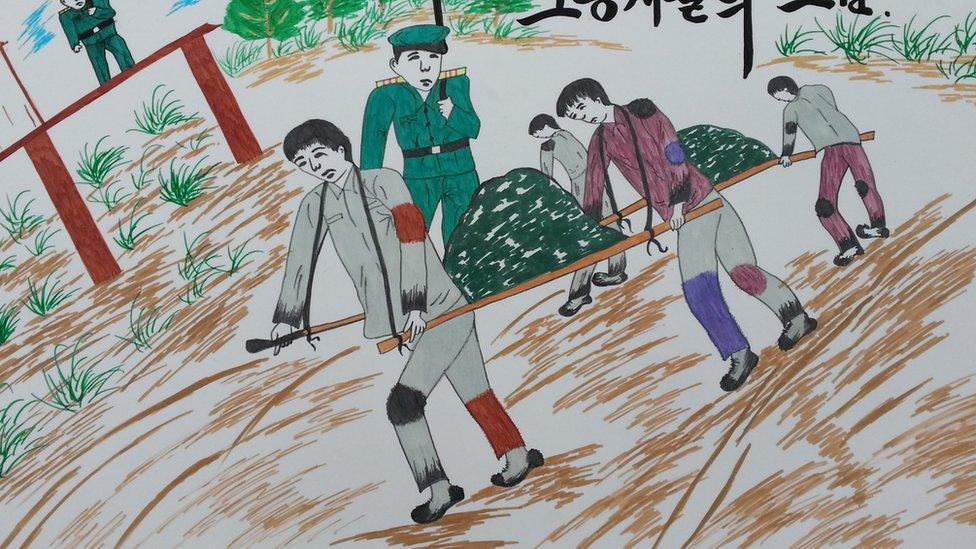

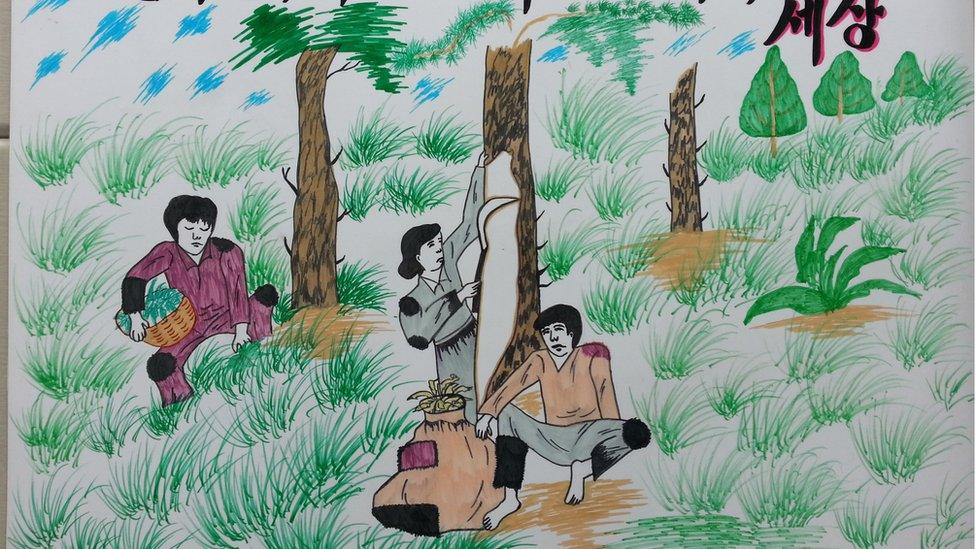

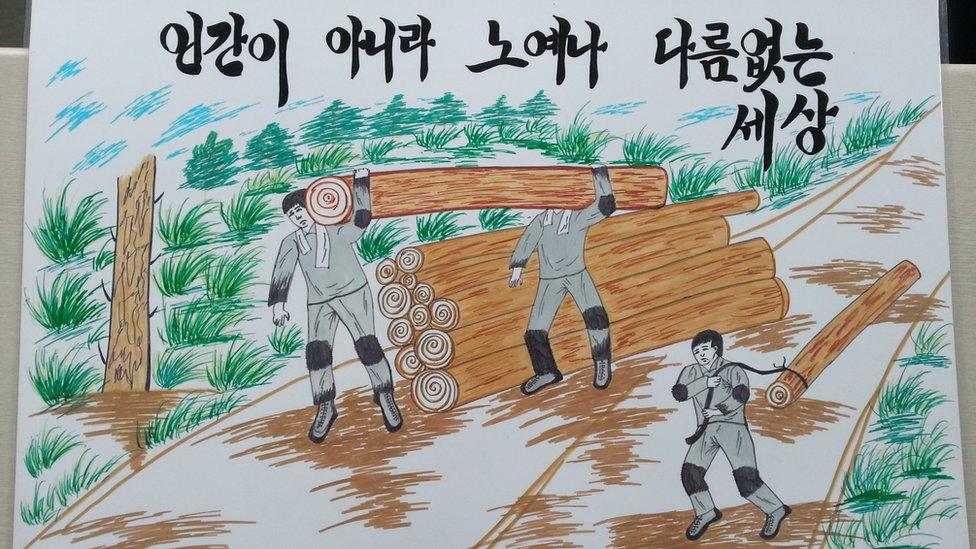

Former prisoner Kim Hye-sook drew these depictions of her experience in a North Korean coal mine

Generations of South Korean prisoners of war are being used as slave labour in North Korean coal mines to generate money for the regime and its weapons programme, according to a report released by a human rights organisation. The BBC has taken a closer look at the allegations.

"When I see slaves shackled and dragged on TV, I see myself," Choi Ki-sun told me. He was one of an estimated 50,000 prisoners seized by North Korea at the end of the Korean War in 1953.

"When we were dragged to labour camps, we were at gun point, lined up with armed guards around. What else could this be if not slave labour?"

Mr Choi (not his real name) said he continued to work in a mine in North Hamgyeong province alongside around 670 other prisoners of war (POWs) until his escape, 40 years later.

It is not easy to get stories out of the mines. Those who survive, like Mr Choi, tell stories of fatal explosions and mass executions. They reveal how they existed on minimal rations while being encouraged to get married and have children who - like Mr Choi's - would later have no choice but to follow them into the mines.

"Generations of people are born, live and die in the mining zones and experience the worst type of persecution and discrimination throughout their lifetime," explains Joanna Hosaniak, one of the authors of a new report, Blood Coal Export from North Korea, from the Citizens' Alliance for North Korea Human Rights (NKHR).

The report outlines the inner workings of the state's coal mines and alleges that criminal gangs, including the Japanese Yakuza, have helped Pyongyang smuggle goods out of the country earning untold sums of money - one report estimates the figure at hundreds of millions of dollars - which is thought to be used to prop up the secretive state's weapons programme.

The report is based on the accounts of 15 people who have first-hand knowledge of North Korea's coal mines. The BBC interviewed one of the contributors and we have independently heard from four others who claim to have suffered and escaped from North Korea's coal mines. All but one person asked us to protect their identity to keep their remaining families in North Korea safe.

Pyongyang consistently denies allegations of human rights abuses and refuses to comment on them. It insists all POW's were returned according to the armistice terms, with a government official previously saying that any who remained wished "to remain in the bosom of the republic".

But Mr Choi says this is not true. He told us that he lived inside a fenced-off camp guarded by armed troops.

At first he was told that if he worked hard enough he would be allowed to go home. But eventually all hope of returning to the South faded.

Workers as young as seven

The current system of forced labour in North Korean coal mines appears to have been set up after the Korean War. The report by the NKHR described it as "inherited slavery".

South Koreans were taken to major coal, magnesite, zinc and lead mines mostly in North and South Hamgyeong Provinces, according to the human rights group investigation.

But not everyone who ends up in the mines is a prisoner of war.

Kim Hye-sook was told by guards that her grandfather went South during the war and that is why she was sent to work in the coal mine with her family as a teenager.

Her fate was determined by her "songbun" - or class, a judgement made on how loyal a family has been to the regime and how many are members of the Worker's Party of Korea.

Connections to South Korea automatically puts a person in the lowest class.

Ms Kim was just 16 when she started work in the mine. The NKHR report has accounts from survivors who said they started part-time work in the mine from age seven.

"When I first got assigned there were 23 people in my unit," she recalled. "But the mines would collapse and the wires that pulled the mine trolley would snap and kill the people behind it.

"People would die from explosions while digging the mines. There are different layers, in the mines, but sometimes a layer of water would burst and people could drown. So in the end only six remained alive of the initial 23."

'Death is a good ending'

But your "songbun" doesn't just determine your fate in the mines - it can also determine whether you live or die, according to a former member of the Ministry of State Security (MSS) quoted in the NKHR investigation.

"You try to let loyal class people live. You try to kill off people from a lower class."

But he said any executions - mainly of "South Korean spies" - were done according to "North Korean laws".

"You need the data analysis to show it's very justifiable to kill this person. Even if they've committed the same crime, if your class is good they will let you live. They don't send you to the political prison camp. You go to an ordinary prison or a correctional labour camp.

"You don't kill them because death is a good ending. You can't die, you have to work under orders until you die."

The interviewee described a "shooting gallery" at the back of the MSS interrogation room where some prisoners were killed. He said some were publicly executed while others were killed quietly.

The BBC has been unable to independently corroborate this account. But we did hear from Ms Lee who remembers the moment her father and brother were executed.

"They tied them to stakes, calling them traitors of the nation, spies and reactionaries," she told my colleagues from BBC Korean in an interview.

Her father was a former South Korean prisoner of war and that meant she too was forced to work in the mines.

Ms Lee's father had praised his South Korean hometown, Pohang and her brother had repeated that claim to his workmates. Ms Lee said that for that, teams of three executioners shot both of them dead.

'We were always hungry'

North Korean officials appear to have allowed the prisoners of war some aspects of normal life within the mining camps. They gave the miners citizenship in 1956. For most, that was the moment they knew they were not going home.

All of our interviewees were allowed and even encouraged to get married and have children. But Ms Kim believes this too had a purpose.

"They would tell us to have a lot of children. They needed to maintain the mines but people died every day. There are accidents every day. So they would tell us to have a lot of children. But there's not enough food and no diapers etc - so even if you do give birth to a child it was hard to raise them successfully."

Ms Kim was released from the prison camp in 2001 as part of a country-wide amnesty, and eventually escaped from North Korea by crossing a river near the border with China.

She decided to sketch illustrations of her 28 years in the mine, saying it helped her deal with some of her nightmares, and show others what she'd been through.

'I was forced to work in a North Korean coal mine'

Hunger was a constant problem for all our interviewees and is documented in the NKHR report.

"A day didn't pass without going hungry. We were always hungry. One meal a day, we didn't know other people ate three times a day. We were given long grain rice, which continues swelling soaked in water," Ms Kim told us.

One former prisoner of war told us that even if they were sick they needed to go to work.

"If you missed a working day, then your meal ticket could be taken away," he said.

Miners were given quotas to fulfil, he told me, estimated at around three tonnes of anthracite (a form of hard coal) a day by the NKHR report. Not meeting it could mean no meal ticket which meant going hungry.

'Slavery' funding weapons programme

The United Nations Security Council banned North Korean coal exports in a bid to choke off funding for its nuclear and ballistic missile programmes.

But two years later, a report by independent sanctions monitors said that Pyongyang had earned hundreds of millions of dollars "through illicit maritime exports of commodities, notably coal and sand".

In December, the United States said North Korea continued "to circumvent the UN prohibition on the exportation of coal, a key revenue generator that helps fund its weapons of mass destruction programs".

The NKHR report also claims that the mines are continuing to expand.

Deputy Director Joanna Hosaniak called on the UN to fully investigate North Korea's dependence on slavery and forced labour including "the full extent of the extraction and illegal export of coal and other products, and the international supply chain linked to these exports".

"This should also be enforced through a clear warning system for the businesses and consumers."

In the South, the administration has focused on engagement with Pyongyang and even discussed the possibility of a peace economy with the North. Seoul has argued that taking a more aggressive approach on human rights would see Pyongyang storming away from the negotiating table and could also lead to an increase in hostilities.

But a report by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Seoul said it was time to "integrate human rights into the peace and denuclearisation talks" which should also involve input from North Korean defectors.

Many still suffering

For two former prisoners of war who were forced to work in the mines there has been some hope, however. They won a landmark legal victory after Seoul Central District Court ordered North Korea and its leader, Kim Jong-un, to pay them $17,600 (£12,400) in damages for holding them against their will and forcing them to work in the mines.

This was the first time a court in the South recognised the suffering of prisoners of war held in the North.

Mr Choi was one of them.

"I am not sure I will see the money before I die but winning is more important than money," he told me at his apartment south of Seoul.

But his mind always returns to those left toiling in the mines as he serves me a plate of fruit which would once have been an unthinkable luxury. He tells me he's trying to send his family in the North some money.

"I think of how much they must be suffering while now I am happy," he sighed.

Illustration by Kim Hye-sook.

You may also be interested in:

Shin Dong-hyuk tells 5 live about his experience via a translator

Related topics

- Published18 February 2019

- Published14 April 2018

- Published21 November 2017

- Published5 September 2023

- Published16 February 2021