Afghanistan: Will America's 'moonshot' peace plan work?

- Published

Boys play in front of a mural of Zalmay Khalilzad, the US envoy, and Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the leader of the Taliban delegation

US President Joe Biden's team calls it a "moonshot"; critics question if it's a "quick fix"; and millions of Afghans wonder if it's the blueprint to end an endless war, or just make it worse.

An apparent draft of a new peace agreement from the office of the US peace envoy in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, has been leaked after doing the rounds in the Afghan capital, Kabul. The eight tightly typed pages, which were obtained by the BBC along with a leaked three-page letter from US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, have kicked up a political storm over the past 48 hours.

In his letter, Mr Blinken wrote that the US did "not intend to dictate terms" to the Afghan government and the Taliban, only enable both sides to "move urgently" towards peace.

But the plain-speaking Afghan Vice-President, Amrullah Saleh, fired straight back, saying Afghanistan would "never accept a bossy and imposed peace".

"They can make decisions on their troops, not the people of Afghanistan," Mr Saleh said.

A Taliban spokesman, Zabiullah Mujahid, told the BBC they were "still studying" the draft agreement. But he also stressed that they expect the US to meet the terms of the deal they signed last year. In other words, pull out the remaining 10,000 US-led Nato forces by 1 May, or else.

A moonshot is the kind of imagining which soars beyond "blue sky" brainstorming. It's the biggest of ideas to solve the very biggest of problems. In Afghanistan, it's nothing less than life and death: how, after two long decades, to withdraw without precipitating a spiral into greater violence.

Zalmay Khalilzad has returned to Kabul with a new sense of urgency amid a US push for peace

"Dignified" is another new buzzword in this dreadful war: a dignified US departure; a dignified peace for Afghans.

"We do need to explore every avenue for a dignified peace to preserve rights and a fundamental set of values, including a democratic system of governance," said the Afghan government negotiator, Nader Nadery.

Mr Khalilzad, the US envoy, landed in Kabul last week with a new sense of purpose. His presence and draft plan sparked political electricity behind the ugly high walls protecting the elegant drawing rooms of the capital. It is focusing minds in a precarious moment when Afghanistan teeters on a knife edge between war and peace.

"There's an accelerating momentum and a greater sense of urgency," former President Hamid Karzai told the BBC in Kabul last week. There's even more toing and froing than usual in his heavily fortified bastion in the capital; his meeting room, with its traditional oblong arrangement of sofas and chairs, was packed on the day the BBC dropped by.

Cobbling together the "unity and inclusivity" called for in Mr Blinken's letter is Mr Karzai's forte. Warlords of past battles shut out by President Ashraf Ghani are being brought to the top table again, for better or worse. Some, who had reached out to the Taliban to seal their own futures and fortunes, are said to have realised that the cost of disunity could be chaos and collapse.

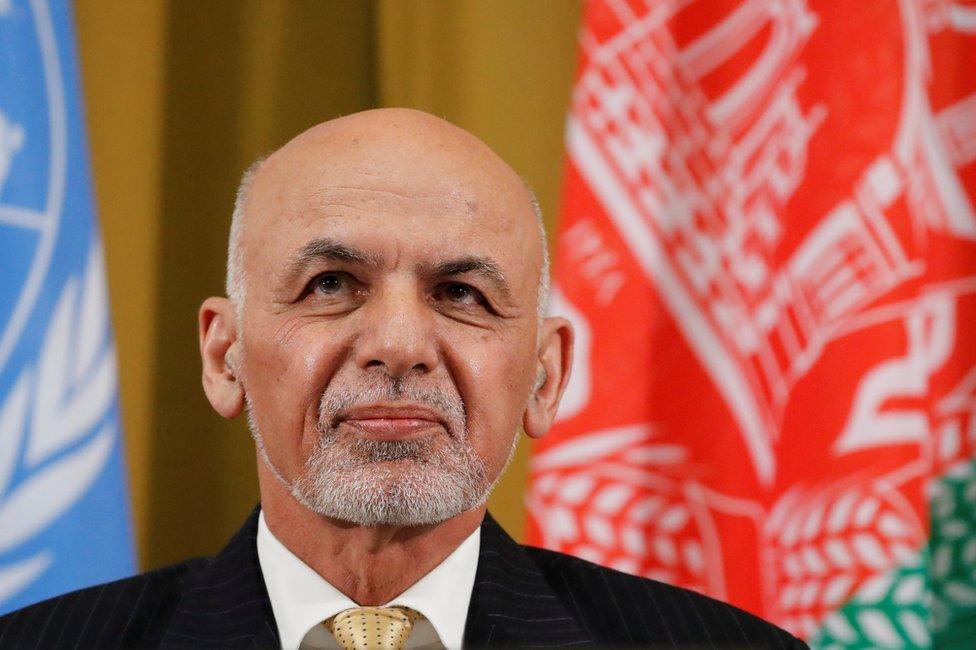

Mr Ghani, known to prefer an immersion in policy papers to the messy cut and thrust of politicking, is also being pushed back into the fray. In his book-lined office last month in the storied Haram Sarai, the former residence of King Zahir Shah, President Ghani hinted that this was crunch time: "Hard decisions and sacrifices lie ahead," he told us.

But when asked about Mr Khalilzad's previous draft of a power-sharing government, he dismissed it as "somebody sitting behind the desk, dreaming".

So will President Ghani, who still insists he'll only transfer power through elections, accede to this transition plan? One Afghan politician summed it up to us with an Afghan proverb: "If you don't go to school, you'll be taken to school." In other words, Mr Ghani might have no choice.

And what about the country's warlords - will they put aside age-old animosities for peace? They may, but with "hearts full of blood" - another proverb, and a warning that old feuds may not lie dormant for long.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called on President Ashraf Ghani to show "urgent leadership"

The draft paper sets out a new arrangement in three parts: guiding principles for Afghanistan's constitution and the future of the Afghan state; agreed terms to govern the country during a transitional period and a roadmap to a "durable and just settlement"; and finally - and most urgently for Afghans - agreed terms for a "permanent and comprehensive ceasefire and its implementation".

There are blank spaces and options as well. The length of a transitional government is marked "XX". Two possibilities for an executive administration are offered: one similar to the current arrangement led by a president and vice-presidents; another which includes a prime minister.

In an effort to expedite the process, the US is pulling out all the stops and calling in all the favours. The UN, kept largely on the sidelines until now, is shifting to centre stage to confer greater international legitimacy on the process, and make it easier for neighbours who have long meddled in Afghanistan to sit around the same table. Mr Blinken's letter also proposed a high-level meeting in Turkey to bring warring sides together.

And there is something for everyone in the eight-page draft peace agreement. The Taliban will note a suggestion for a High Council for Islamic Jurisprudence to provide "Islamic guidance and advice" - though it's likely to fall far short of what the Taliban herald as the return of a "pure Islamic government".

Women's groups will see, on the very first page, that "the future constitution will guarantee the protection of women's rights". If anyone knows that words alone are never enough, it's the women and girls whose lives have changed, but remain heavily circumscribed, whether or not the conservative Taliban are in power.

The brother of an assassinated female media worker waits to receive her body in Jalalabad last week

And millions of Afghans, hearts hollowed out by grief, will press for progress towards what this paper calls "a national policy of transitional justice" - even though they know that the arc of history in Afghanistan has never bent towards justice.

"Bringing lasting peace primarily depends on the Afghan sides, but the international community led by the US was a stakeholder in this conflict, and their responsibility doesn't end with ensuring a safe exit for their troops," said Shaharzad Akbar, chairwoman of the Afghanistan's Independent Human Rights Commission.

"They still have leverage with both Afghan sides of the conflict and can utilise that to push for substantive discussions to end the suffering of Afghans through talks," she said.

There are those who caution against too much hope: "The only attractive argument for this plan is [if] its success means a ceasefire," said Laurel Miller, the director of the Asia Programme at the International Crisis Group and a former US state department official. "But if the weak, fractious, transitional structure collapses - which is a high probability - then the ceasefire won't last."

Peace is on the agenda as never before, but so is war. Both sides talk of plans for the worst of all summer offensives. "It will be a miracle if this works," one Afghan involved in the peace effort told us.

But in a country that has lived through almost everything, aiming for moonshots and miracles may not seem far-fetched. The people are anxious for the endless war to end, and as soon as possible.

- Published28 February 2021

- Published22 February 2021

- Published18 February 2021