Myanmar coup: What protesters can learn from the '1988 generation'

- Published

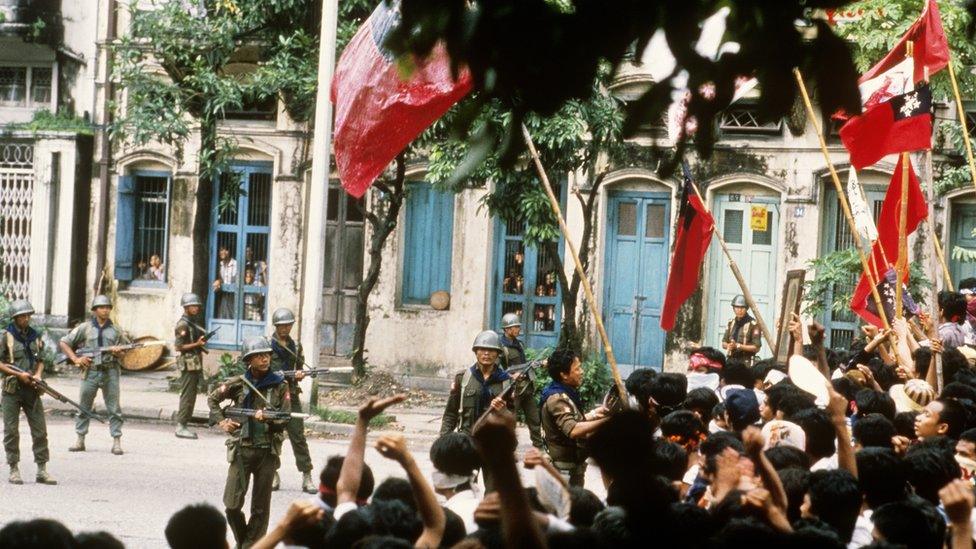

Which of the two coups? This image shows the protests of 1988

Student activists lead a movement to bring an end to a widely-hated military government in Myanmar. It grows into a nationwide uprising, a general strike, which is met with savage brutality by the armed forces. 2021? Or 1988?

The 1988 uprising remains one of the defining moments of Myanmar's modern history. A regime which had used extreme levels of violence to hold onto power, suddenly found itself facing massive protests over its calamitous mishandling of the economy.

By 1988 Burma, as the South East Asian nation was then known, had been ruled for 26 years by the secretive and superstitious General Ne Win, who seized power in a coup in 1962. He was commander of the armed forces - known as the Tatmadaw - which had been fighting insurgencies in several parts of Burma since independence in 1948, and viewed civilians as incapable of holding the country together.

General Ne Win cut Burma off from the outside world, refusing to take sides in the Cold War divisions then afflicting Asia. Instead he implemented an eccentric one-party system under his Burma Socialist Programme Party, in which the army played a dominant role, and led to Burma becoming one of the world's poorest countries.

The political drama which culminated in the mass rallies of August and September 1988 actually began one year earlier, with Ne Win's sudden decision to demonetise all existing banknotes. This had a catastrophic economic impact, in particular on students who had saved up their tuition fees.

'The 88 generation'

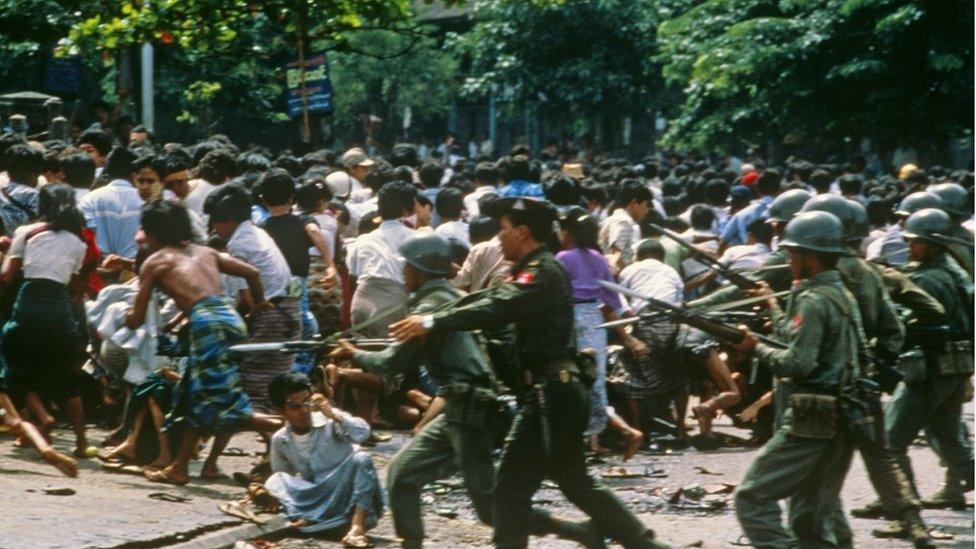

The confrontations with the military government escalated from that point, with soldiers using increasing levels of lethal force, to the point where they killed thousands in late 1988. The violence used against unarmed civilians since last month's coup has been shocking, but it's not at that level - yet.

To this day the so-called "88 Generation" of students, who led that uprising, have a special status in Myanmar. Many of them spent up to two decades in prison, where deprivation and ill-treatment robbed them of their health, but not their fighting spirit. Some have even been out in today's protests.

Thousands were killed in the 1988 crackdown

But they are no longer young - the best known 88 Generation leader Min Ko Naing is 58 years old - and the protest environment has been dramatically transformed by technology, allowing every confrontation to be filmed and uploaded immediately, and many of the abuses by the security forces to be recorded.

Social media v pamphlets

So today, people even in the farthest-flung parts of Myanmar are instantly aware of what's happening anywhere in the country as news of protests and crackdowns appear on Facebook and Twitter there almost as quickly as those in the big cities.

Back in 1988 however, the students relied on crudely-printed pamphlets and word of mouth to communicate; Burma had very limited access to television or even old-fashioned telephone landlines. The scratchy, short-wave broadcasts of BBC World Service were a lifeline, both for Burmese and English speakers.

Christopher Gunness, the young BBC reporter who was one of the few foreigners who managed to report from there for a short time during the tumultuous events of August, became a folk hero, as his broadcasts helped spread the word about the general strike called for 8.8.88 - where hundreds of thousands came out to protest before a bloody crackdown.

And it was the 26 years of economic isolation and wretched poverty which motivated protesters in 1988, not a sudden power grab after 10 years of democratic rule, as now. In 2021 those leading the protests want to preserve economic possibilities and access to the world that, in the past decade, have been far in excess of what their parents had.

"The 1988 uprising started more because of unhappiness with the socialist system in Myanmar," says Ye Laung Aung, a civil servant now active in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM).

"When that collapsed the military took over. But in 2021 the military seized power by force from an elected National League for Democracy government. That is the big difference. We have joined the CDM because we recognise only the elected NLD government. In 1988 civil servants stopped going to work largely because of public disorder and violence. Today we refuse to work because we do not want to be part of a coup administration."

Aung San Suu Kyi v thousands of leaders

1988 also saw the emergence of a clear leader of the opposition movement in Aung San Suu Kyi, who was in the country at that time originally only to care for her ailing mother. She formed the National League for Democracy, a highly centralised and top-down organisation, together with former senior military officers like Aung Gyi and Tin Oo.

By contrast, today's movement is often called "leaderless", but in fact has thousands of leaders, all responsible for organising their local part of this loose and flexible structure.

The 2021 protest is organised without Aung San Suu Kyi at the helm

Lessons from the past

Where 1988 can serve as a useful reference point for today's generation of activists is in the lessons they can learn.

In 1988 protesters were too quick to celebrate the installation of a notionally civilian leader, and too slow to organise themselves into a unified movement.

Ne Win had resigned in July, and his successor, General Sein Lwin, called the "Butcher of Rangoon" for his part in the 8.8.88 suppression of demonstrations, lasted only 17 days.

But divisions within the movement over which direction to take, and growing lawlessness in an increasingly fearful population as local administration disintegrated in the power vacuum, set the scene for a military coup on 18 September. That ushered in more than 20 years of harsh, authoritarian rule, with Aung San Suu Kyi, the symbol of hope for that generation, destined to spend most of those two decades under house arrest.

There was little co-ordination, even communication, in 1988 between the student protest movement and the many ethnic minorities who had been fighting for a less centralised, more federal system of government since independence. Mistrust between the ethnic Burman majority and Myanmar's sizeable minorities endures to this day.

However, younger activists in the CDM are now openly demanding a more inclusive and representative form of politics, and apologising for their past neglect of the terrible abuses suffered by the Karen, the Kachin and the Rohingyas.

No return to the status quo

"While everyone agrees on the enemy - the military - they are also increasingly aware that things cannot return to the status quo: merely respect the vote and so forth, putting Aung San Suu Kyi back in that uneasy power-sharing relationship with the military," says Elliot Prasse-Freeman, assistant professor in Sociology/Anthropology at the National University of Singapore, who has written extensively on Myanmar.

"And so, ironically, the military has forced this reckoning, in which mainstream liberals are now forced to confront the reality that the so-called democracy of the last 10 years was merely that: so-called."

The experience of military rule after the 1988 uprising, when the generals enriched themselves through corrupt business deals, has robbed the armed forces of the grudging respect they once had in the wider population as guarantors of the country's unity.

Myanmar coup: How did we get here?

Now they have also broken the pledge they made, back in 1988, to allow a move towards democracy, albeit on their own chosen timescale and conditions. And they have forced a realisation on the people of Myanmar that, whatever they say, they will never willingly give up the grip they have had on the country for most of its 73 years of existence.

This helps explain why so many are now risking their lives to try to stop this coup, unlike previous coups, from succeeding.

"The generals could always say, with a certain if strained plausibility, that they eventually fulfilled their promise, post-1988, for a democratic transition," says Elliot Prasse-Freeman.

"They can no longer say that, and the entire apparatus has now become, in the eyes of most people, nothing more than a terrorist organisation - this is the term used on social media in both English and Burmese [akyan-pet thama]. In daytime the police and other security officials beat and kill peaceful protesters; at night, videos are circulating in which they smash cars, destroy trishaws, and randomly shoot at civilians.

"The military has long seen civilians as enemies. But these actions, so desperate and inhumane, demonstrate how vast the gap between them has become."

Myanmar in profile

Myanmar, also known as Burma, became independent from Britain in 1948. For much of its modern history it has been under military rule

Restrictions began loosening from 2010 onwards, leading to free elections in 2015 and the installation of a government led by veteran opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi the following year

In 2017, Myanmar's army responded to attacks on police by Rohingya militants with a deadly crackdown, driving more than half a million Rohingya Muslims across the border into Bangladesh in what the UN later called a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing"

Related topics

- Published10 March 2021

- Published11 March 2021

- Published6 March 2021

- Published7 March 2021