Why Narendra Modi's visit to Bangladesh led to 12 deaths

- Published

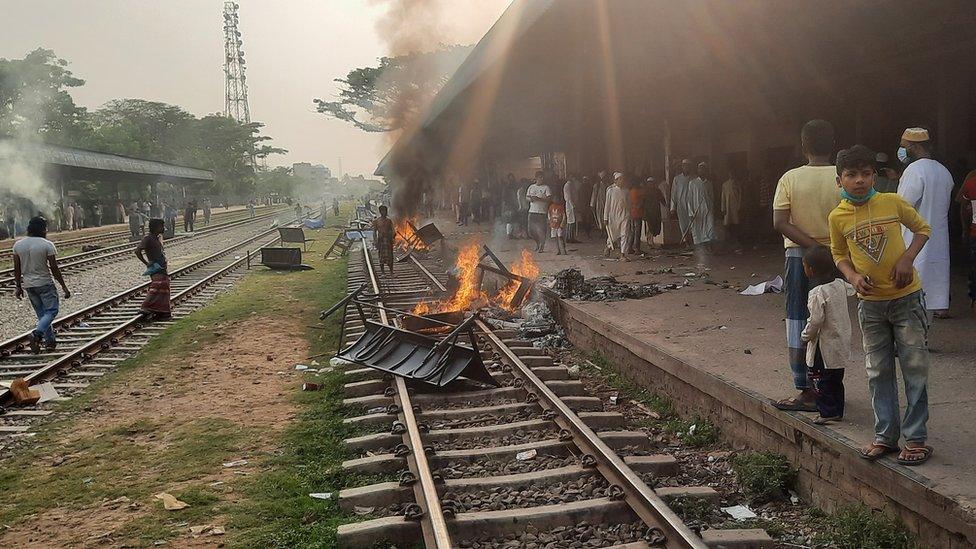

Protests against Mr Modi's visit left 12 people dead

Bangladesh had hoped that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's presence at its 50th independence anniversary celebrations last week would be memorable.

But the visit turned deadly as violent protests broke out against Mr Modi, leaving at least 12 people dead.

Mr Modi is a polarising figure both at home and abroad. His government, led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has often been accused of pursuing policies that target Muslim minorities, and not doing enough to curb violence against them. The BJP denies the charges.

His contentious image appears to have sparked the protests in the capital Dhaka - and the violence that followed no doubt was an embarrassment to both countries. It also casts a shadow on what has always been an amicable relationship between India and Bangladesh.

What happened in Bangladesh?

Mr Modi arrived in Dhaka for a two-day visit on 26 March, Bangladesh's independence day. It also coincided with the birth centenary of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the country's founder and father of the current prime minister, Sheikh Hasina.

Leaders of the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Bhutan and Nepal were all guests of honour at the event. But Mr Modi's visit, which was meant to cap off the 10-day long celebrations, set off protests.

A group of Muslim worshippers held a protest on 26 March after Friday prayers at a mosque in the city. Soon, clashes erupted and police used tear gas and batons to disperse the crowd.

Protests then spread to other parts of the country and a hardline Islamist group, Hefazat-e-Islam, called for a nationwide shut down on 28 March to protest the attacks on those who held rallies against Mr Modi's visit.

Islamists and left-wing groups led the protests

Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the crowd, which threw rocks and stones at security forces.

Dhaka and the eastern district of Brahmanbaria witnessed some of the worst violence, external. Buses, a train, a Hindu temple and several properties were damaged. A number of people with gunshot wounds were admitted to hospitals.

"Madrassa students holding processions were attacked by security forces and supporters of the [governing] Awami League. That led to the conflict. But there was no need to open fire on unarmed people," Dr Ahmed Abdul Qader, vice chairman of the Hefazat, told the BBC.

Officials say 12 protesters have died so far but the Islamist group say there were many more casualties.

"Bangladesh is a democracy and everybody has a right to say what they have to say. But they [the protesters] cannot take law and order in their hands," Anisul Haq, Bangladesh's law minister, told the BBC.

"They [the protesters] exceeded the limit. To protect the citizens of the country, and to protect law and order, the law enforcing agencies intervened," Mr Haq said.

Why were they protesting?

The protests were led by Islamists, students of madrassas (religious schools) and left-wing groups opposed to Mr Modi's visit to Bangladesh. They accused him of pursuing anti-Muslim policies.

Those who organised the rallies and even supporters of the ruling Awami League have accused security forces of brutally attacking protesters.

The incident prompted a group of eminent citizens and activists to issue an open statement, external demanding justice for the attacks on protesters.

Protesters accuse Mr Modi of being anti-Muslim

Despite good bilateral relations, there has always been an undercurrent of anti-India sentiment among a section of Bangladeshis.

After the BJP came to power in India in 2014, "the anti-India sentiments turned into more of an anti-Modi feeling in Bangladesh", Shireen Huq, a women's rights activist, told the BBC.

"The protesters were not against India or the people of India. They were angry at the invitation to Mr Modi, who's extremely controversial and who's known for his anti-Muslim stance," she added.

"Bangladesh could have invited the president of India. That would have been acceptable to everyone."

But the government has justified its decision to invite Mr Modi.

"The government and the people of Bangladesh want to invite somebody from a country which steadfastly helped in our nine-month long independence war," Mr Haq said.

Does the violence affect bi-lateral relations?

India and Bangladesh have historically enjoyed a good relationship.

Bangladesh was formerly East Pakistan. It became a part of Pakistan when the Britain divided the subcontinent into a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan in 1947.

But in 1971, Bangladesh fought for its independence from Pakistan and with the help of Indian military intervention, it became a separate country.

But the BJP's rise to power has complicated matters.

Ms Hasina (left) is facing domestic pressure for being too pro-India

In recent election campaigns in the border states of West Bengal and Assam, Mr Modi and other senior BJP leaders have often raised the issue of alleged unauthorised immigration from Bangladesh. Bangladeshi officials have denied the accusation.

In a 2019 election rally, Home Minister Amit Shah described illegal immigrants as "termites", adding that the BJP government would "pick up infiltrators one by one and throw them into the Bay of Bengal, external".

Mr Shah's comments drew sharp criticism from rights groups and triggered anger in Bangladesh too.

But the repeated references to unauthorised Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh, especially during polarising election campaigns, have caused resentment in Dhaka. Ms Hasina's government, which is seen as pro-India by the opposition, is facing domestic pressure.

In 2019, Mr Modi's government passed a contentious citizenship law that would give asylum to religious minorities fleeing persecution from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. By definition, that does not include Muslims.

The Citizenship Amendment Act was seen as anti-Muslim and it drew widespread criticism from India's opposition parties and rights groups.

The controversial law took Dhaka by surprise as well.

Ms Hasina went on the defensive and denied that minorities were fleeing Bangladesh due to religious persecution. Hindus constitute around 8% of Bangladesh's population of more than 160 million.

At one point Bangladesh even cancelled a few high-profile ministerial visits to India, external following domestic criticism of the citizenship law and a proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Trains, buses and a Hindu temple were damaged in the clashes

The final NRC in Assam has left out nearly two million, including Hindus and Muslims, who ostensibly lacked sufficient documentation to prove that they were not unauthorised immigrants from Bangladesh. Hindu hardliners want the Muslims who have not made it to the list to be deported to Bangladesh.

Another thorn in the bilateral relationship is the killing of Bangladeshi civilians along the border by Indian security forces. Rights groups allege that more than 300 people have been killed since 2011, external and the shootings have triggered widespread anger in Bangladesh.

Indian officials say most of those killed are smugglers from criminal gangs. But Bangladesh maintains that many of the victims were civilians. Activists point out that despite repeated assurances from Delhi, the killings have not stopped.

"India-Bangladesh relations has been one-way traffic. Bangladesh has given lots of concessions to India without getting much in return. Still, we have many unresolved issues like the sharing of river water," Ms Huq said.

The two countries share 54 rivers and except for one, they all flow from upstream India to Bangladesh before reaching the Bay of Bengal. So India has the ability to regulate the water flow. But except for the Ganges, the two countries have not yet signed an agreement on any other river, much to the displeasure of Bangladeshis.

Maintaining a good relationship with Bangladesh is key to India's security in its north-eastern region where several indigenous separatist groups operate. Many of them have been subdued over the years with Dhaka's help.

India often boasts of its "excellent" relationship with Bangladesh. It's seen as a silver lining in its diplomacy in its backyard given Delhi's troubled ties with other neighbours such as Pakistan and China.

The anger over Mr Modi's visit is therefore a clear warning to Delhi - if the sensitivities of its neighbour are not addressed, India may end up being friends only with the government in Dhaka and not with the people of Bangladesh.

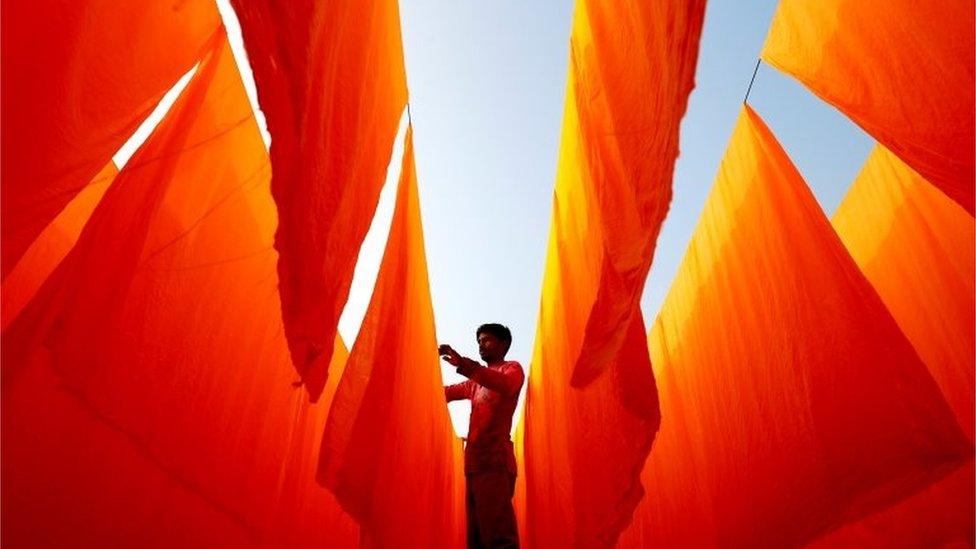

Bangladesh: Losing my job as a garment factory worker

Related topics

- Published24 March 2021

- Published26 March 2021

- Published21 February 2020