Prince Philip: The Vanuatu tribes mourning the death of their 'god'

- Published

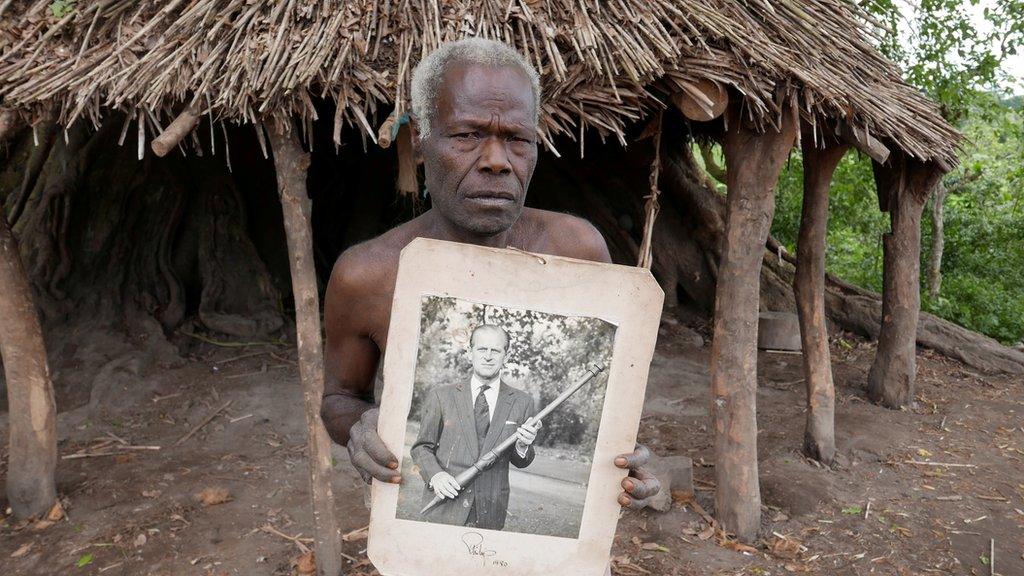

Prince Philip corresponded with the villagers over the years, and sent pictures of himself holding a ceremonial club they gave him

As Britons mourn the death of Prince Philip, they are joined by a tribal community on a Pacific island half a world away.

For decades, two villages on the Vanuatuan island of Tanna have revered the Duke of Edinburgh as a god-like spiritual figure.

A formal period of mourning is now under way.

On Monday, scores of tribespeople gathered in a ceremony to remember Prince Philip.

"The connection between the people on the island of Tanna and the English people is very strong... We are sending condolence messages to the Royal Family and the people of England," said tribal leader Chief Yapa, according to Reuters news agency.

For the next few weeks, villagers will periodically meet to conduct rites for the duke, who is seen as a "recycled descendant of a very powerful spirit or god that lives on one of their mountains", says anthropologist Kirk Huffman who has studied the tribes since the 1970s.

They will likely conduct ritualistic dance, hold a procession, and display memorabilia of Prince Philip, while the men will drink kava, a ceremonial drink made from the roots of the kava plant.

This will culminate with a "significant gathering" as a final act of mourning. "There will be a great deal of wealth on display" which would mean yams and kava plants, says Vanuatu-based journalist Dan McGarry.

"And also pigs, because they are a primary source of protein. I would expect numerous pigs to be killed for the ceremonial event."

Monday's meeting saw a couple of hundred people gather under giant banyan trees, according to Mr McGarry who is on Tanna.

There were speeches remembering Prince Philip, but also discussion about a possible successor. At sunset the men drank kava.

The BBC understands that a private message to Queen Elizabeth has been given to journalists at the scene, who will convey it to British officials.

Over the weekend villagers in Yaohnanen prepared kava roots for a mourning ceremony

'A hero's journey'

For half a century, the Prince Philip Movement thrived in the villages of Yakel and Yaohnanen - at its height, it had several thousand followers, though numbers are thought to have dwindled to a few hundred.

The villagers live in Tanna's jungles and continue to practise their ancestral customs. Wearing traditional dress is still common, and while they maintain strong links with society, money and modern technology such as mobile phones are seldom used within their own community.

Though they live only several kilometres from the nearest airport, "they just made an active choice to disavow the modern world. It's not a physical distance, it's a metaphysical distance. They're just 3,000 years away," says Mr McGarry, who has frequently met the villagers.

The villagers live in traditional houses in the jungle of Tanna

The villagers' centuries-old "kastom", or culture and way of life, sees Tanna as the origin of the world and aims to promote peace - and this is where Prince Philip has played a central role.

Over time, the villagers have come to believe he is one of them - the fulfilment of a prophecy of a tribesman who has "left the island, in his original spiritual form, to find a powerful wife overseas", says Mr Huffman.

"Ruling the UK with the help of the Queen, he was trying to bring peace and respect for tradition to England and other parts of the world. If he was successful, then he could return to Tanna - though one thing preventing him was, as they saw it, white people's stupidity, jealousy, greed and perpetual fighting."

With his "mission to literally plant the seed of Tanna kastom at the heart of the Commonwealth and empire", the duke was thus seen as the living embodiment of their culture, says Mr McGarry.

"It's a hero's journey, a person who sets off on a quest and literally wins the princess and the kingdom."

Prince Philip was seen as the embodiment of Tanna "kastom"

Nobody is sure exactly how or why the movement began, though there are various theories.

One idea, according to Mr Huffman, is that villagers may have seen his picture along with the Queen's on the walls of British colonial outposts when Vanuatu was still known as New Hebrides, a colony administered jointly by Britain and France.

Another interpretation is that it emerged as a "reaction to colonial presence, a way of re-appropriating and taking back colonial power by associating themselves with someone who sits at the right hand of the ruler of the Commonwealth", says Mr McGarry, pointing to the sometimes violent colonial history of Vanuatu.

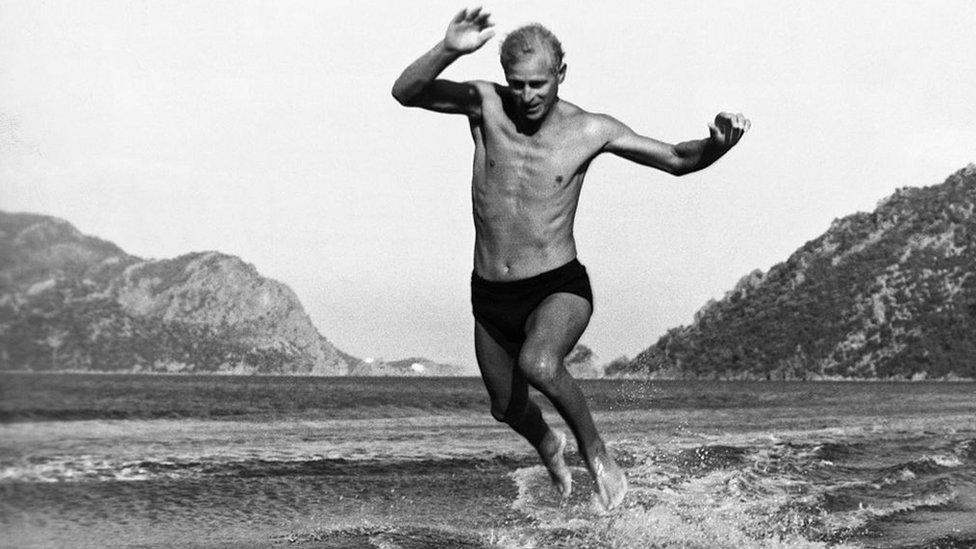

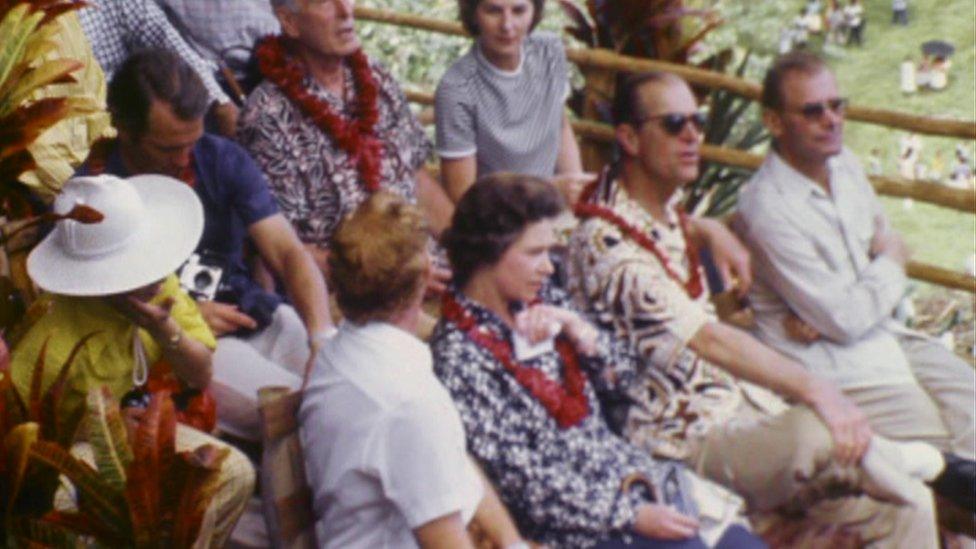

But experts are certain that by the 1970s, the Prince Philip Movement already existed, cemented by the royal couple's visit in 1974 to New Hebrides where the duke reportedly took part in kava-drinking rituals.

Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth, seen in the front row, watched traditional ceremonies on Pentecost Island in New Hebrides

What did Prince Philip make of it all? Publicly, he appeared to accept their reverence, sending several letters and photographs of himself to the tribesmen, who in turn have plied him with traditional gifts over the years.

One of their first presents was a ceremonial club called a nal-nal, given at a 1978 meeting convened by villagers to ask for more information about Prince Philip, which Mr Huffman attended.

"So the British resident commissioner went down, made a presentation of photos of Prince Philip. Hundreds of these people were just waiting around, sitting or standing under the bushes. It was so quiet, we could hear a pin drop," says Mr Huffman.

"One of the chiefs then gave a club to pass to Prince Philip, and wanted proof that he received it."

It was sent all the way to the UK, where pictures of the duke holding the club were taken and sent back to the villagers. Those photos, among other memorabilia, are still treasured by the villagers to this day.

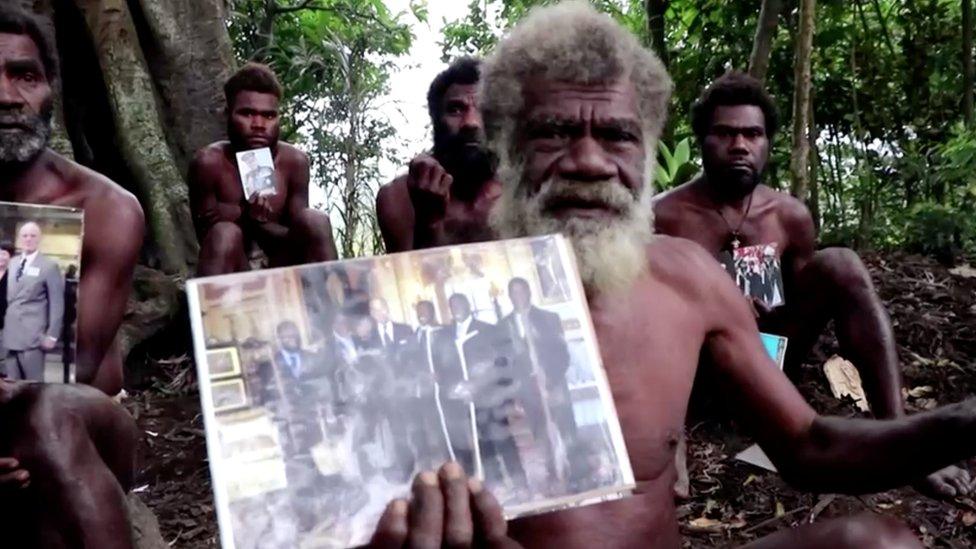

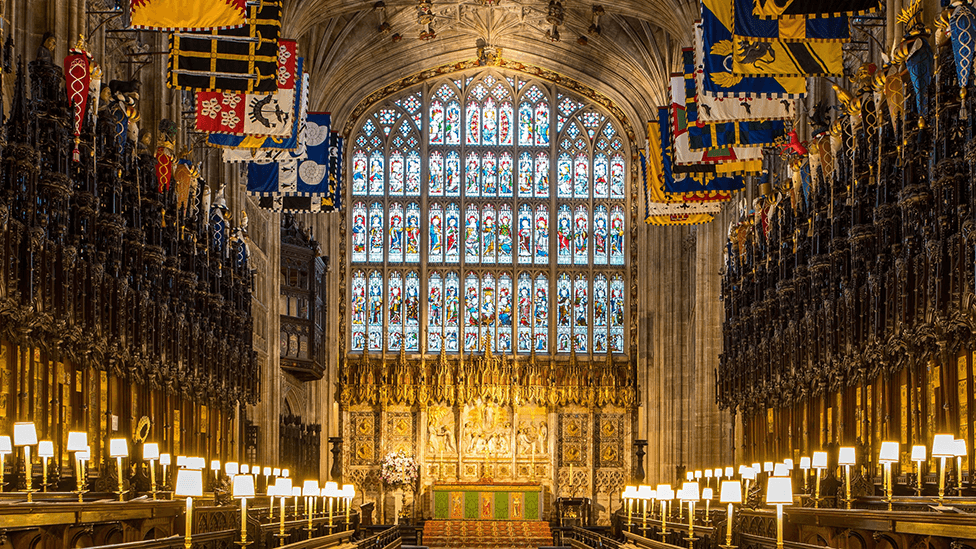

In 2007, several tribesmen met the duke in person. Flown to the UK for the Channel 4 reality television series Meet the Natives, five tribal leaders had an off-screen meeting with the duke at Windsor Castle where they presented gifts and asked when he would return to Tanna.

His reply, as reported by the tribesmen later, was cryptic - "when it turns warm, I will send a message" - but appeared to please them.

Though Prince Philip was known for his frankness and has been criticised in the past for being culturally insensitive, on Tanna "he is seen as very supportive and sensitive", says Mr Huffman.

Chief Yapa was one of several tribesmen who met Prince Philip in Britain in 2007 and took pictures with him

His connection with the tribes has continued through Prince Charles, who visited Vanuatu in 2018 and drank the same kava his father did decades ago. He also received a walking stick on behalf of the duke from a Yaohnanen tribesman.

A son continuing his father's mission?

The duke's death has now inevitably opened up the tricky question of who will take his place in the tribes' spiritual pantheon.

Discussions are already under way, and it may take some time before they decide on his successor.

But for observers familiar with Vanuatu, where tribal custom usually dictates that the title of chief is inherited by male descendants, the answer is obvious. "They might say, he has left it to Charles to continue his mission," says Mr Huffman.

Even if Prince Charles becomes the latest incarnation of their deity, Prince Philip will not be forgotten any time soon. Mr Huffman says the movement are likely to keep its name, and one tribesman has told him they are even considering starting a political party.

But more importantly, "there has always been the idea that Prince Philip would return some day, either in person or in spiritual form", says Mr Huffman, who adds that some may think his death will finally trigger this eventuality.

And so, while the Duke of Edinburgh lies in rest in Windsor Castle, there is the belief that his soul is making its final journey across the waves of the Pacific Ocean to its spiritual home, the island of Tanna - to reside with those who have loved and revered him from afar all these years.

Prince Philip: Officer, husband, father

Related topics

- Published27 October 2023

- Published25 January 2017

- Published9 April 2021

- Published17 April 2021

- Published9 April 2021