Covid-19: Singapore schools tackle mental health amid pandemic stress

- Published

A recent spike in Covid cases in Singapore saw a return to online learning for many children

Millions of children across the globe have dealt with months of learning from home as countries struggle with the pandemic. Now, as many begin returning to school, thoughts have turned to not only the lost education, but also the long term impact on their mental health.

In Singapore, which has one of the world's top school systems, they are opting to tackle the issue head on.

Children around the world have suffered from feelings of stress, anxiety and isolation as the pandemic locked down communities and shut schools for months at a time over the past year.

In the UK, where schools were shut for the best part of half a year, a government report said one in six children aged five to 16 had a probable mental health disorder in 2020 - up from one in nine three years earlier. The situation is similar in the US, where hospitals saw a 31% rise in mental health emergency visits by 12- to 17-year-olds in April to October from a year earlier, according to the CDC, external.

In Singapore, in a reminder of last year, a recent spike in cases - including some in schools - has prompted tighter measures across the city-state. As part of efforts to keep people further apart, students went back to online learning for 10 days in late May.

But in its highly academic, competitive environment, even this short break was enough to pile extra worry onto students.

"I think a lot of us put a lot of pressure on ourselves to do well in studies, especially after the lockdown," said 14-year-old Kate Lau. "Things are a lot more under control compared to what it was. But then I am still a little bit worried."

Prior to the pandemic, mental health was rarely discussed in Singapore's academically rigorous schools - but that now appears to be changing.

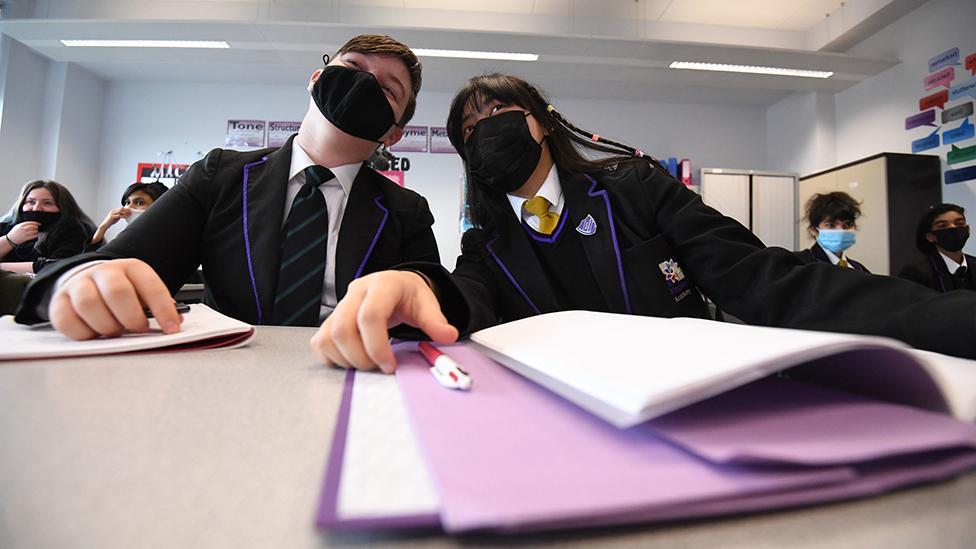

Mask-wearing and social distancing has become the norm for many schoolchildren across the world

The small country - which consistently ranks at or near the top of global exam scores - is paying close attention to the lingering effects of the Covid crisis on children, which left some families struggling to cope.

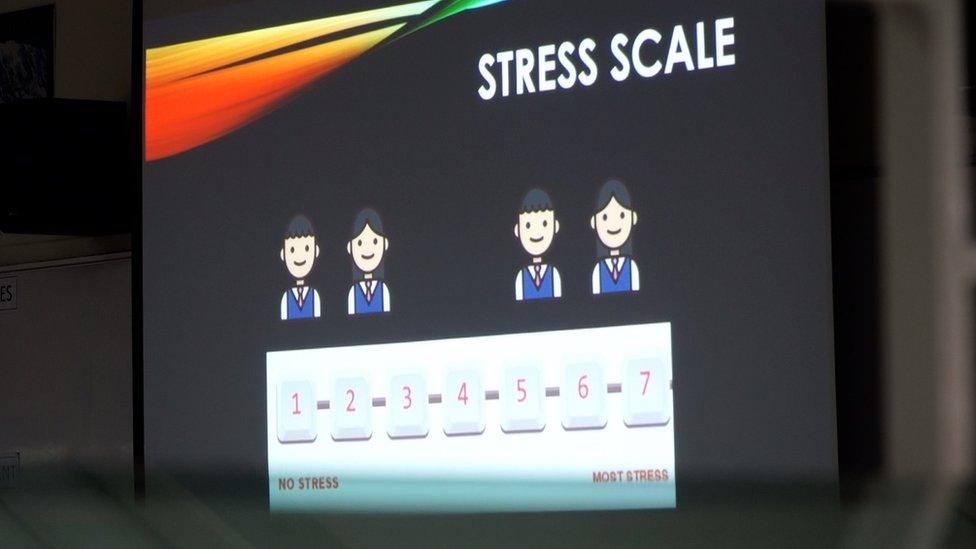

This year, weekly sessions started at primary and secondary schools to encourage students to talk about their feelings and improve how they handle stress and anxiety. Sessions feature animated videos to help students identify and cope with stress, while teachers share their personal experiences to encourage the free flow of ideas and discussions.

"Some of the children felt they were isolated at home throughout the whole lockdown period," said Michael Chow, a teacher at Serangoon Secondary School. "I think these lessons are very important as it helps us to drive the point across that, hey, you're not alone here and, hey, these are real issues that you are facing."

Children are being encouraged to share their concerns and anxieties using animated videos

For the children, nothing is entirely normal. They must always wear a mask and keep their distance while still ensuring they complete hours of homework every day and maintain good grades.

These new realities - combined with existing expectations - pile on the pressure, said Dr Tazeen Jafar, a professor of health services and systems research at Duke NUS Medical School who has been studying the impact of Covid in various parts of the world.

"Children spending a lot of time doing their homework tend to spend less time doing social activities and tend to play less and sleep less," she said.

"Those are risk factors for depression and anxiety so they are already pre-disposed and then any added external pressure like the pandemic makes them more and more susceptible."

These issues are reflected in other parts of Asia that also put heavy emphasis on academic excellence.

In pre-Covid times, mental health was rarely discussed in Singapore's top performing schools

Studies in China on children's psychological distress due to the pandemic showed female adolescents have a higher risk of depression and anxiety, Dr Jafar said. The studies also showed senior high school students nearing college entrance exams are more depressed than younger pupils.

But dealing with the underlying anxiety is further hampered in a region where a stigma around mental health can prevent it being discussed openly.

In a number of Asian countries, having a mental health condition is sometimes viewed as "losing face", a term used to the cultural idea of being shamed and losing dignity. While some people view it as "just a phase".

In 2015, a study at the Singapore Institute of Health found that there is a "considerable" stigma towards people with a mental illness which could prevent individuals from seeking treatment.

Half of people who took part in the survey, external said they saw poor mental health as a sign of personal weakness and nine in 10 felt that people with mental illnesses could get better if they wanted to.

The Singapore mums asking suicidal teens to "please stay"

Singapore's new modules in schools - alongside awareness training for teachers, nurses and counsellors - are a "very nice mechanism" that could help to change attitudes about mental health more broadly, said Dr Jafar.

"If successful, the model will be great to emulate across the region," she said.

Listening to the students, it does seem to be working in Singapore.

"The programme helped me speak out a bit more," Kate Lau tells the BBC. "I'm more open now to sharing my feelings in front of a class or telling my friends or teachers how I feel."

Muhammad Rayyaan Khan, who is 15, agrees. "If I have anxiety I would definitely speak up."

- Published22 March 2021

- Published5 December 2016

- Published5 March 2021

- Published7 March 2021