'War on Terror': Are big military deployments over?

- Published

The few thousand remaining western forces are leaving Afghanistan after 20 years

Western forces are racing to leave Afghanistan this month. France has signalled a significant scaling back of its military commitment in Mali. In Iraq, British and other Western forces no longer have any major combat role.

Twenty years after President George W Bush's so-called War on Terror, is the era of big "boots-on-the ground" military deployments to distant warzones coming to an end?

Not yet - there is still a substantial commitment to fighting jihadists in the Sahel - but there is now a radical rethink in how these missions are conducted.

Large-scale, long-term deployments have been hugely costly, in blood, in money and in political capital at home.

The US-led military presence in Afghanistan has cost more than $1tn (£724bn) and thousands of lives on all sides - Afghan forces, Afghan civilians, western forces as well as their insurgent foes.

At their peak in 2010, Western troop numbers topped 100,000. And yet now, after 20 years in the country, the few thousand remaining forces are leaving just as the Taliban looks set to take over more and more territory.

Achilles' heels

The longer and larger a military commitment is in fighting an insurgency, the more vulnerable it becomes to a variety of potential "Achilles' heels".

The most obvious of these is the casualty rate, a trend that can become seriously unpopular back home.

More than 58,000 Americans died in the Vietnam War and nearly 15,000 Soviet soldiers in Afghanistan - factors that hastened the end of those campaigns. France has lost just over 50 soldiers in Mali since 2013 and its mission there has largely lost its support at home.

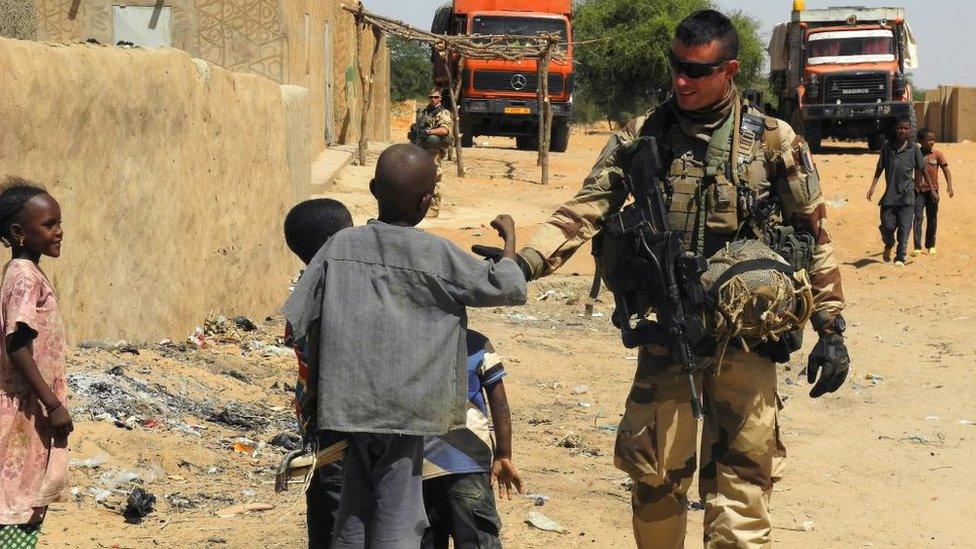

France has had a mission in Mali since 2013

Then there is the financial cost, which almost invariably exceeds expectations.

When Saudi Arabia began its intervention in Yemen's civil war in 2015 it never expected to be still fighting there six years later. Estimates of the running cost to the Saudi treasury to date range as high as $100bn (£72.4bn).

Concerns over human rights can also derail a military campaign when least expected.

US air strikes hitting Afghan wedding parties, Saudi air strikes killing civilians in Yemen and human rights abuses by the UAE's allies there have all carried a reputational cost for those countries.

In the case of the UAE, the stories emerging of prisoners being suffocated to death while locked inside shipping containers had a major influence in prompting it to withdraw from the Yemen war.

Then there is the possibility that the host government could end up sharing power with a hostile entity.

In Mali, reports that the government is engaged in secret talks with the jihadists were enough to cause President Emmanuel Macron to threaten to pull out French forces altogether.

In Iraq, says retired British Army Col James Cunliffe, "there is still a real concern about Iranian influence, especially when it comes to the Shi'a militias".

In Afghanistan, the Taliban, who were driven out of power in 2001, are expected to make a comeback. Western security officials say if they end up being a part of the government then all intelligence co-operation would cease.

Read more from Frank Gardner:

No easy answers

It is clear that there are no easy answers to the problem of failed states and dangerous dictators. Let's take a look at some recent examples:

Iraq, 2003-present day: A massive US-led military invasion, backed by Britain, followed by years of occupation and a bloody insurgency. Despite much recent progress, the whole experience has been so scarring that it has been enough to deter politicians from any large-scale military intervention in the Middle East for a generation, perhaps longer

Libya, 2011-present day: A brief, Nato-imposed no-fly-zone but no significant western boots on the ground. It was enough to enable the anti-Gaddafi rebels to depose his regime in 2011. But the country then imploded into a civil war and jihadist insurgency. Initial Libyan gratitude then turned to anger at being "abandoned" by the West

Syria, 2011-present day: An extreme reluctance by western powers to become involved in the civil war between President Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian rebels. Big power intervention was left to Russia, Iran and Turkey. There has been 10 years of violence that still simmers on

Islamic State group, 2014-2019: The one clear military success story with an 80-nation coalition eventually defeating and dismantling the brutal and sadistic caliphate calling itself Islamic State. But it took five years and relied heavily on destructive air power and some awkward alliances on the ground with Iranian-backed militias in Iraq. IS is now stepping up its operations in Africa

Mali, 2013- present day: The initial French military intervention saved the capital Bamako from almost certainly being overrun by al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadists. But eight years on, despite the presence of thousands of multinational troops, the insurgency continues and France's president has indicated his displeasure with Mali's rulers and his intention to scale back its commitment

The Future

So if big, open-ended military deployments are no longer going to be in vogue, then what replaces them?

One clue can be found in the speech delivered on 2 June at the Royal United Services Institute's Land Warfare Conference by the UK Chief of General Staff, General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith.

Today's Army, he said, will be "more networked, more expeditionary and more rapidly deployed, more digitally connected, linking satellite to soldier and centred on a Special Operations Brigade".

Top US commander General Scott Miller reflects on NATO forces' time in Afghanistan ahead of its departure

Fewer boots on the ground inevitably means a greater reliance on cutting-edge digital technology, including artificial intelligence.

Trends emerging from recent conflicts have prompted a radical rethink in strategic priorities. The brief war in the Caucasus between Azerbaijan and Armenia saw the latter's tanks getting decimated by cheap, unmanned, armed drones supplied by Turkey and directed to their targets at almost no risk to the operators.

Mercenaries, once considered a throwback to a bygone era in Africa, have been making a comeback.

The most obvious example here is Russia's shadowy Wagner Group which has allowed Moscow "plausible deniability" while operating with few restrictions in conflict zones from Libya to West Africa to Mozambique. "A state-centric world order," says Dr Sean McFate, senior fellow at the Washington-based Atlantic Council, "is giving way to a war without states."

None of this means an end to military missions overseas. In Mali and the Sahel the French may be winding up their single-nation Operation Barkhane and sending thousands of troops home. But the UN mission continues and the French are retaining a reduced force committed to a multinational counter-terrorism mission.

In Iraq, the Nato mission will continue to train local counter-insurgency forces and offer them technical support.

In Afghanistan however, the western military presence is disappearing over the horizon at the very time it may be needed most to confront a combined threat from the Taliban, al-Qaeda and Islamic State.