West Africa's Islamist insurgency: Fight at a critical stage

- Published

French troops are leading the fight against jihadists in West Africa

The multinational effort to stave off an encroaching takeover by extremists in the part of Africa known as the Sahel is facing severe challenges.

Mali, where around 400 British troops are currently deployed, has just experienced its second coup in nine months, widely condemned by regional leaders.

President Emmanuel Macron has threatened to pull out all 5,100 French troops there if the coup leaders carry out their suggestion of making a deal with the same Islamist insurgents the troops are fighting.

Further north, Spain has pulled out of US-led multinational war games dubbed African Lion over a dispute with Morocco.

This matters for West Africa and the region but it could also have a knock-on effect for other parts of the world.

This part of Africa, the Sahel, is the transit route for huge numbers of migrants making their way northward to Europe. It is also a major transit route for illegal drugs, weapons and jihadists.

Some expect an increased flow of migrants making the perilous journey north from places like Niger, pictured here,

Both the Islamic State group and its rivals in al-Qaeda have taken a strategic decision to make Africa their new priority after suffering setbacks in the Middle East.

If chaos, violent extremism and insecurity become the norm in Sahel nations like Mali then we are likely to see two things emerge: firstly, a new geographic base from which jihadists can plot attacks around the world and secondly, an increased flow of migrants and refugees making the perilous journey north to Europe to escape from their own countries.

The current strategy is effectively only one of containment, of trying to limit the reach of the jihadist insurgents and prevent them from seizing and holding significant swathes of territory.

Abuses by security forces

The Sahel's problems - drought, corruption, poverty, unemployment and ethnic friction - go far deeper than that. Julie Coleman, Senior Research Fellow at the International Centre for Counter Terrorism in The Hague, argues that the predominately security-focussed approach has been counter-productive as it has failed to address the underlying problems that have driven so many young Malians to join extremist groups.

"In the last eight years since the international community intervened in Mali," says Ms Coleman, "the situation has got worse. The number of Malians joining insurgent groups has increased and so too has the number of attacks."

Part of this she puts down to "gross violations of human rights" by security forces including extra-judicial killings and arrests based on ethnicity.

Drought is one of the Sahel's many problems

But even containing and restraining the threat from jihadist insurgents presents enormous challenges.

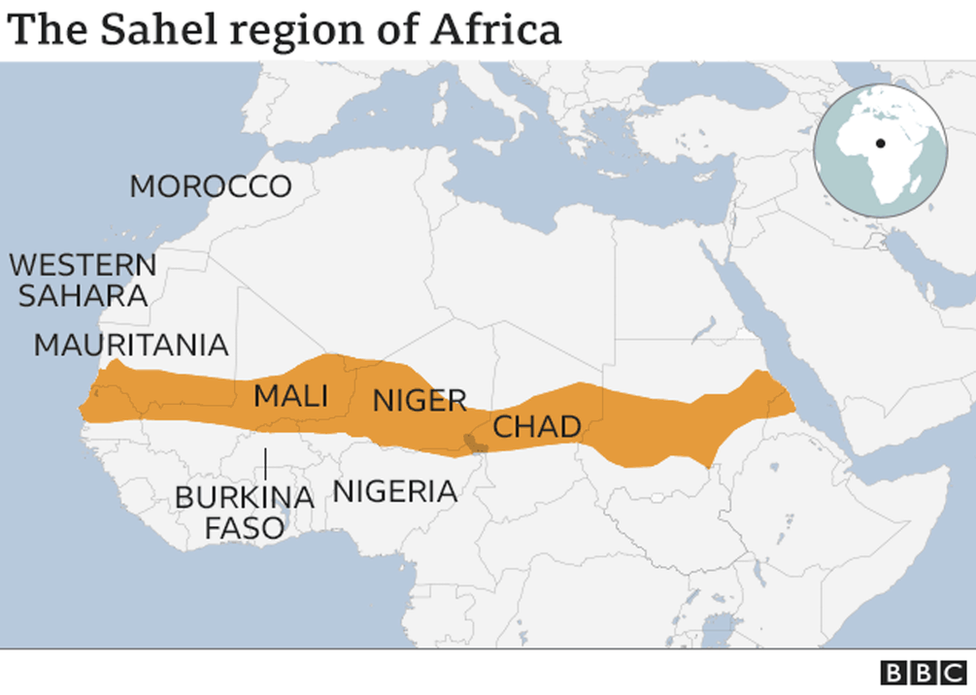

The Sahel, an area that stretches across Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso, is vast - nearly three million sq km [1.16m sq miles] - with jihadistattacks spilling over into neighbouring Nigeria. It is sparsely populated, largely impoverished and poorly policed with porous borders exploited by drug runners, people smugglers and transnational terrorist groups.

No country can tackle this on their own. So even though it was France that intervened with lightning speed in 2013 to prevent an al-Qaeda affiliate from overrunning the Malian capital Bamako, it was subsequently agreed that a collective effort was essential. Two military missions now run concurrently:

There is the UN peacekeeping mission, comprising 56 nations and over 14,000 troops. Some of these are now engaged, alongside Malian forces, in long-range reconnaissance patrols deep into the desert, reaching out to remote communities in an effort to reassure them there is a government-backed security presence.

Then there is the separate, French-led counter-terrorism mission, Operation Barkhane. Using drones, helicopters and a base in Niger, the French, backed by US intelligence, are hunting down jihadist cells that operate across the region's borders.

Mali: The world's 'most dangerous peacekeeping mission'

But as experience in Afghanistan has shown all too clearly, even well-armed and focussed Western intervention can only go so far. For counter-insurgency to succeed in the longer term it needs two things: competent local forces and the support of the local population.

In Mali this is a particularly acute problem. In many parts of the country there is little public confidence in the local forces which are spread impossibly thinly and with two coups in under a year the political situation is extremely fragile.

Several local politicians have called in the past for French and other foreign forces to leave and with more than 50 French service personnel losing their lives there since 2013, this campaign is not popular at home.

France has now stopped working with Mali's army

After the latest coup, President Macron was quoted this week as saying: "France would not stand by a country where there is no democratic legitimacy."

"The trouble with such a vast and hostile terrain," says a Western security expert who asked not to be named, "is that it requires huge investment of resources to make any impact at all. Couple that with a poor quality of local forces and you have a problem."

The US has long recognised the danger of transnational terrorist groups taking root in the Sahel but here politics have made life harder for those engaged in counter-terrorism.

Without better governance in the Sahel, little will change for its people

One of the last acts of President Donald Trump's administration was to recognise Morocco's sovereignty over the disputed former Spanish colony of Western Sahara, which Morocco occupied in 1975.

Spain objects to this, insisting that the territory's Saharawi people have a right to self-determination. In April it allowed the leader of the Saharawi resistance group, the Polisario, to be treated for Covid in a Spanish hospital.

In retaliation, Morocco allowed up to 10,000 migrants to rush the Spanish border at Ceuta before most were returned. Now Spain has pulled out of African Lion, the largest annual military manoeuvres organised by US Africa Command and due to take place this month in Western Sahara and involving 7,000 troops from nine nations.

Coups, corruption and disunity among allies are all gifts to insurgent groups. They take the focus off counter-terrorist operations, allowing the insurgents to regroup, rearm and plot future attacks.

The situation in the Sahel is precarious but there is enough at stake that those countries already engaged are likely to remain so for the near future. But unless military assistance expands into a comprehensive programme for better governance for its people, then this risks being an operation without any discernible end.