The Philippines' food worries amid Ukraine war and typhoons

- Published

Farmer Felix Pangibitan posted a video about his rice crops

Felix Pangibitan runs his hands through what is left of his precious rice crop.

The stalks in nearly two-thirds of the field are bent double; most are flattened, others have been snapped at the neck by strong typhoon winds which reached more than 150mph (241km/h).

"It looks so pitiful," he says in a video which has now gone viral across the Philippines.

"It's a waste. It's so hard to be a farmer."

It's a loss both Felix and the country can ill afford - especially this year, as food costs have soared to alarming levels.

His farm in Nueva Ecija on the main island of Luzon was one of thousands in the path of a powerful storm which hit the country's so-called "Rice Bowl". More than $22m (£18.2m) worth of crops were destroyed in 24 hours.

"I can't remember all the typhoons and their names but this has been the most heartbreaking one yet," he told us.

His simple heartfelt videos struck a chord across the Philippines, especially among the poorest communities which have been hit by multiple crises.

As in much of the world, the price of food, fuel and fertiliser have all increased here since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February.

But the Philippines is particularly vulnerable. It has to import food - including rice and all cereals such as wheat - to feed its growing population, making it one of the most food-insecure countries in Asia.

Filipino farmers grow rice but some has to be imported

And as Felix can testify, even the food the Philippines does grow is far from guaranteed in a country which is the most disaster-prone in the world.

Typhoons batter the islands with growing frequency and severity. There have been a total of 16 severe storms this year which have destroyed or partially damaged more than $225m (£186m) worth of agricultural land, according to the latest figures from the Department of Agriculture.

This country may need more farmers to feed them, but farmers are already struggling to feed themselves. More than two million people who rely on farming are living below the poverty line.

"Our situation right now is the hardest so far," said Felix, who's been farming for 30 years.

"The price of goods has increased, along with fertilisers and fuel. Meanwhile, the price of our crops has stayed the same for decades. It means what we harvest is worthless."

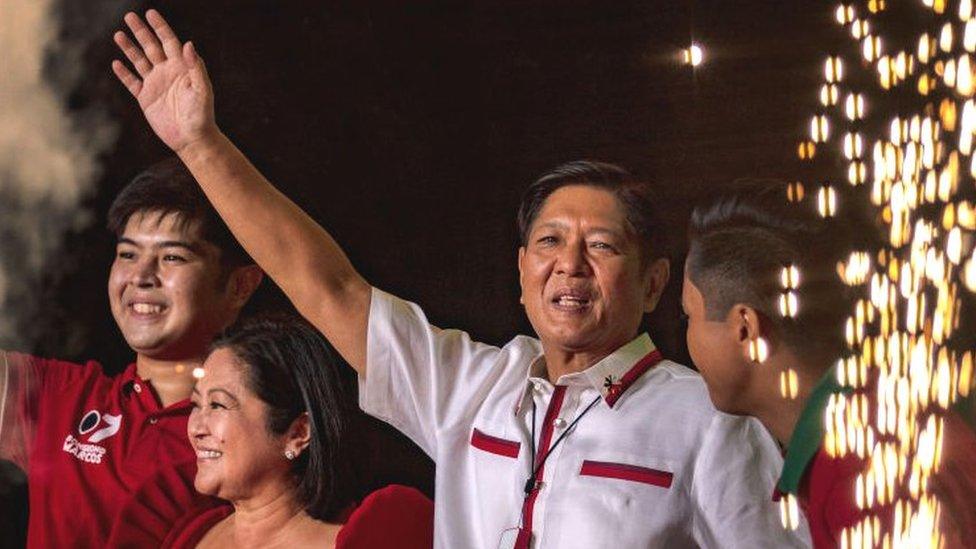

Philippines President Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr has appointed himself as minister for agriculture and promised to get the country growing again. But even he has admitted that inflation is running "rampant and out of control" mostly due to rising food costs.

Last month's 8% inflation rate is the highest recorded since November 2008, when it soared to 9.1% - and it's hitting ordinary Filipino families hard.

Forty-one-year-old Mary Ann Escarda pushes her squeaky cart through a maze of dark back alleys in the capital Manila every morning before dawn. She sells bread rolls known as pandesal to commuters, which earns her around $4 a day - just under the minimum wage in the Philippines. Her husband also brings home a salary. But even their combined income is not enough to feed their four children.

"To save food, I have put the children on a diet. We used to eat three times a day but now we only eat lunch and dinner," she told us as she gave one of her children the last of the powdered milk.

She lives in a small house with 17 members of her family to keep costs low.

She's also facing a dilemma. The prices of ingredients for her rolls have gone up.

"I can't increase the price to sell them because my loyal customers can't afford that change. They won't buy from me any more if I do.

"I don't know what will happen later - maybe next month when the prices increase, we won't be able to eat. No matter how hard you work, if the prices are just going up, then it's basically nothing."

Mary's family is by no means an exception.

Malnutrition is widespread as the number of Filipinos who cannot afford a healthy diet is rising, according to the Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 report, external. More than a quarter of children under five in the Philippines suffer from stunted growth, the World Food Programme says, external.

This is a resilient country - people do what they can to survive.

But experts believe millions more will face hunger and malnutrition if prices continue to rise.

Many children in the Philippines suffer from stunted growth due to poor nutrition

"We are a very patient people," says Fermin Adriano, a former policy adviser at the Department of Agriculture.

"We will always find a way to cope. But that will change if rice becomes unaffordable. In the minds of the ordinary people - if there's no rice, there is already hunger.

"We can do without sugar, or pork, or white onions. But if there are rice shortages or it becomes hugely unaffordable, then that is the beginning of a real disaster.

"And for the poor, the food crisis is like a plague that hits all their family members, particularly the young ones."

A crisis is hard to detect as dazzling Christmas lights twinkle across Metro Manila. It is one of the biggest holidays of the year and celebrations start as early as September.

The effects of spending now may be felt in the leaner months in early 2023.

President Marcos has approved the extension of reduced tariffs for vital food imports to the end of next year. He also talks of his "dream" that rice will one day sell for 20 pesos (around $0.36) per kilo.

Subsidies may help in the short term, but it's clear that if the Philippines is to one day grow enough food to feed its own people, it will need more farmers.

And persuading the next generation to grow crops when they've watched the losses experienced by the current one could be difficult.

"Do you think we want our children to work in the fields when we experience earning nothing?" said Felix.

"There needs to be a huge change. All politicians say they love the agriculture industry, but we can't feel it."

- Published29 November 2022

- Published29 September 2022

- Published10 May 2022