Why Everest base camp won't be moving anytime soon

- Published

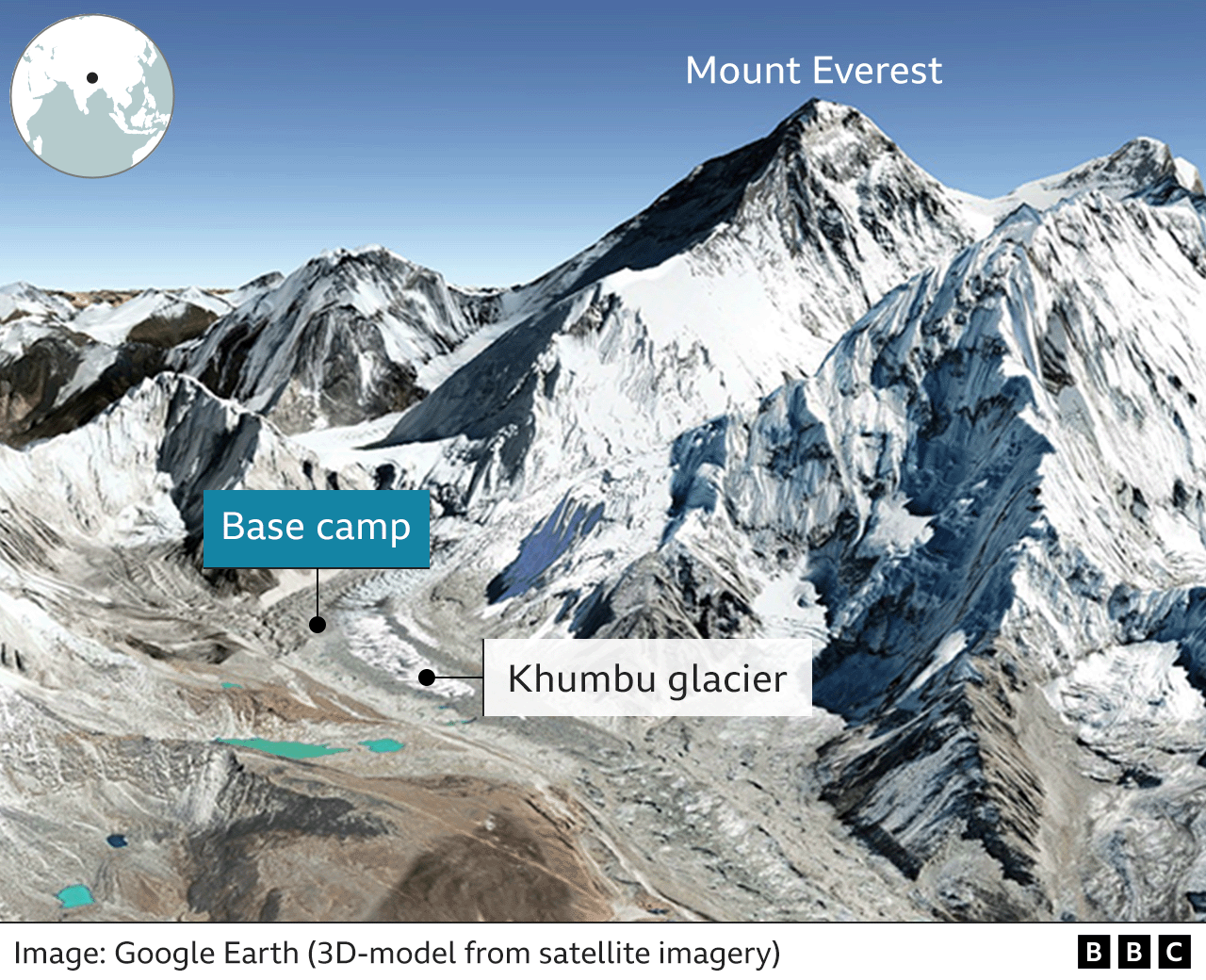

Scientists say the Khumbu glacier on which Everest base camp sits is melting and becoming unstable because of global warming

Last June, Nepal's tourism ministry announced plans to move Everest base camp lower down the famous mountain because global warming and human activity were making it unsafe.

The camp sits on the Khumbu glacier which is thinning rapidly, creating risks for the hundreds of climbers who pass through every year.

But following opposition from the Sherpa community and other mountaineering operators, the idea has been shelved.

Sherpa leaders told the BBC the move was impractical and that there was no viable alternative location.

As the backbone of the mountaineering industry, the Sherpa's voice is crucial. Opposition to the move is widespread - more than 95% of attendees rejected the idea at a recent consultation with the mountaineering industry, say tourism ministry officials and the Nepal Mountaineering Association.

Officials told the BBC it means the move has to be shelved, although they maintain a study is still going on.

'Not a single Sherpa supportive'

"I have come across not even a single person in our community who supports the idea of moving the Everest base camp," said Mingma Sherpa, chair of Khumbu Pasanglhamu, a rural municipality which covers most of the Everest region, including base camp.

"We see no reason for the base camp to be moved in the near future."

Ang Norbu Sherpa, president of Nepal National Mountain Guides Association, echoed that sentiment to the BBC.

"It has been there for the past 70 years, why should they move it now? And even if they wanted to, where is the study on a viable alternative?"

Nepal's recently appointed tourism minister, Sudan Kirati, said the issue was not an urgent one.

"I have seen no interest or concern from any quarter on the issue of moving the base camp," he said.

Thinning glacier, growing risk

When government officials last year spoke of the plan, they said the new base camp would be 200m to 400m (656ft to 1312ft) lower than the present one, which sits at an altitude of 5,364m (17,598ft).

The idea was to move it to a place where there would be no glacier, to avoid risks associated with accelerating glacial meltdown due to rising temperatures.

The Khumbu glacier, like many others in the Himalayas, is rapidly melting in the wake of global warming, scientists have found.

A 2018 study by researchers from Leeds University showed that the segment close to base camp was thinning at a rate of 1m per year.

Field studies have also shown that ponds and lakes on the world's highest glacier were joining up and expanding, increasing challenges for mountaineers.

"As the ice melts, beneath the rocky debris the surface becomes more variable, encouraging the formation of surface ponds that gradually coalesce to form large lakes," said Prof Bryn Hubbard of Aberystwyth University, who led a three-year project to check ice conditions in the glacier.

Mountaineers and officials say streams have now begun to flow right from the middle of the base camp and crevasses are widening dangerously and very quickly.

Scientists say the lakes and ponds on the mountain are growing and joining up due to climate change

Adrian Ballinger, founder of mountain guide company Alpenglow Expeditions, said the plan to move base camp made sense, because it would see more avalanches, ice, and rock falls in the future.

The president of Nepal Mountaineering Association, Nima Nuru Sherpa said he was aware of the dangers in the wake of global warming.

"But there is no clarity on where we move the base camp to, and this is why we hardly hear any supportive voices," he said.

The Khumbu Icefall factor

Many climbers of the Sherpa community have argued that the present location of the base camp is the best one to start their climb early in the morning as it adjoins the Khumbu Icefall, which is one of the most challenging sections of the climb.

The icefall, on the South Col route to the summit of Everest, rapidly falls down the mountain opening large crevasses with little warning and dislodging huge towers of ice, known as seracs. It is also regularly hit by avalanches and rockfalls from the mountain slopes overlooking it on both sides.

Sherpa climbers say they need to cross the Khumbu Icefall early in the morning because it becomes more dangerous later in the day when the sun warms the mountain, resulting in increased avalanches, rockfalls and seracs collapsing.

"If we moved the camp to lower heights, it would mean nearly three hours of extra walk for climbers and that will delay their journey to the dangerous Khumbu Icefall," said Mr Mingma.

Three Sherpa climbers died on Khumbu Icefall on 12 April when they were hit by an avalanche while ferrying climbing gear for their clients.

Mr Mingma said even if the base camp was moved to a lower location, most expedition teams would end up using the previous location as an advanced camp to begin their early morning climb through the Khumbu Icefall.

Lukas Furtenbach, an international expedition operator from Austria who brings his clients to Everest almost every year, says moving base camp would make the first stage of the climb too long.

"Teams would make an intermediate camp right at the current base camp location," he said.

Crowded base camp

But almost everyone in the mountaineering industry agrees that base camp is getting too crowded.

Expedition operators and government officials say the base camp is getting crowded and it needs to be better managed

This season, Nepal issued a record 478 Everest climbing permits, which means there will be over 1,500 people on the mountain, including support staff.

The last record number of permits was 403 in 2021, according to tourism department officials. The government charges $11,000 (£8,900) per climber for Everest and expeditions are a major source of income for the Sherpa community and others dependent on mountain tourism.

"The size of the base camp has doubled over the years, it's a massive operation," said Dambar Parajuli, president of Expedition Operators' Association Nepal.

He added that the growth of the camp is unregulated and poses a threat to the already fragile environment.

"You see deluxe type services like massage parlours or other entertainment services that need massive tents and other structures.

"This is not where you indulge in luxury, and we have strongly suggested the government make strict guidelines on what is allowed and what is not at the base camp."

Minister Kirati said he was aware of the issues.

"The base camp has become like a tourist market that we see here in Kathmandu.

"This is not acceptable - we are soon going there on an inspection and will stop all that. That is our priority now."

Related topics

- Published17 June 2022

- Published27 November 2015