Documenting China's lost history of famine

- Published

Chinese communists launched the Great Leap Forward campaign under Mao Zedong's leadership

The great famine that devastated China half a century ago killed tens of millions of people - but is barely a footnote in history books.

There are few open public records of an event that is seared into the memories of those who survived this largely man-made disaster.

A documentary maker now hopes to redress that imbalance by collecting the stories of hundreds of people who lived through the famine.

He has sent young film-makers across China to video the survivors' testimonies.

Some of those videos have already been shown to the public in screenings at the 798 arts district on the outskirts of Beijing.

Stories are still being collected and the long-term aim is to bring all these video memories together.

Wu Wenguang, the man behind the project, said: "If we don't know about the past, then there will be no future."

Stealing to survive

Armed with video cameras, Mr Wu's researchers have already travelled to 50 villages in 10 provinces across China.

So far they have collected more than 600 memories from the famine, the result of a disastrous political campaign launched by Mao Zedong.

The Great Leap Forward was supposed to propel China into a new age of communism and plenty - but it failed spectacularly.

Agriculture was disrupted as private property was abolished and people were forced into supposedly self-sufficient communes.

Interviews for this new project reveal that even though the famine happened a long time ago - between late 1958 and 1962 - memories are still sharp.

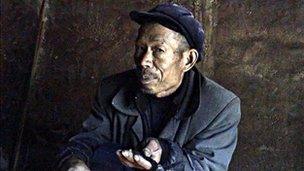

Li Guocheng is just one of those who still have fresh memories on what happened 50 years ago

Those interviewed seem to remember exactly how many grams of rice they were allocated in the period's communal kitchens.

It was sometimes as low as 150g a day, occasionally they got nothing.

Just one of those featured in the public screenings was Li Guocheng, a pensioner from the village of Baiyun in Yunnan province.

He told the story of a relative who was so hungry that he stole a few ears of corn and took them home to cook.

"After he ate them he was caught and tied up with a vine. They bound him to a post at his house," said Mr Li.

But the next day he said the relative did the same again. He was once more caught and once more tied up as punishment.

His 10-year-old daughter was told not to release him.

"The next day he didn't steal again. He stayed home, put a rope over the beam of his house and hanged himself. He was so miserable," said Mr Li.

'Serious mistake'

The researcher who recorded this story is Li Xinmin.

The 23-year-old comes from the same Yunnan village as Mr Li, but it was not until she went back there to video its elderly residents that she realised the full horror of the famine.

"Only occasionally would older people talk about these bitter times - when they had to eat wild vegetables or other stuff that humans wouldn't usually eat," she said.

The 23-year-old is now finding out about a famine she learned little about in school.

Calculating how many people died is difficult. Not every government organisation kept accurate records at the time and there is little official appetite to investigate this dark episode in China's modern history.

798 Arts District was itself a major factory built around the Great Leap Forward period

One Chinese textbook used to teach teenage schoolchildren makes little attempt to explain what happened and why so many people died.

"The party made a serious mistake when it launched the Great Leap Forward and the commune movement as it attempted to build socialism," reads one of the few statements on this period.

Tens of millions of people died, but the book mentions no numbers.

It does not even say people did die - just that the country and its people faced "serious economic hardship".

The only illustration on the page is a poster of an overweight pig.

China is reluctant to talk about this period because those in charge then - the communists - are still in charge now.

To unpick what went on then might encourage people to talk about how the country is ruled today - and that is something the party strongly resists.

'Learn from the past'

Mr Wu, the man in charge of this memory project, thinks Chinese people should know more about the famine.

"We have to know why it happened and what lessons we can learn from it. We have to be warned so it doesn't happen again," he said.

But getting people to talk publicly about it will not be easy.

Mr Wu himself seems aware of just how sensitive this subject still is, decades after it happened.

The title of his project does not mention the word "famine" or the phrase "Great Leap Forward" and he is keen to emphasise that this is an arts project, not a political campaign.

He knows there is little prospect that the current communist-controlled government will suddenly want to look again at this famine.

"Maybe we can change nothing, but at least we can change ourselves," said Mr Wu.

- Published6 July 2011