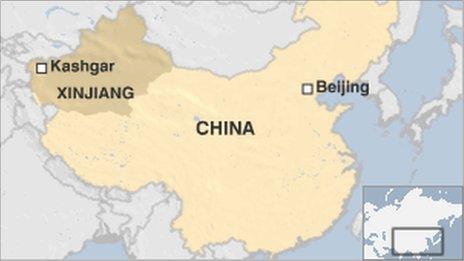

Will development bring stability to restive Xinjiang city of Kashgar?

- Published

The BBC's Martin Patience in the historic city of Kashgar: ''More than half of it has been torn down''

Driving small vans and trucks groaning under the weight of animals, Kashgar's farmers gather at the city's weekly livestock market as they have done for centuries.

Hundreds of sheep, cows and donkeys are corralled or tethered to metal bars where they are inspected by butchers and other prospective buyers.

The sound of bleating and neighing competes against intense haggling over the final price.

Kashgar remains a city where trading is very much in the blood.

It stands on the Silk Road - the trade route of ancient times stretching from the eastern Chinese city of Xian to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

With the advent of major shipping lanes, however, the overland routes fell out of use and Kashgar became something of a backwater.

But now Kashgar is experiencing its biggest economic boom in living memory.

Beijing is pouring billions of dollars into a city which it designated as a special economic zone back in 2010 - one of only half a dozen such zones in the country.

Most people in Kashgar are ethnic Uighurs

The authorities want to transform Kashgar into the transport hub of old - opening up markets in Central Asia and beyond.

"The opportunities here are priceless," says Zhang Yunjian, a spokesman for Gangzhou New City project in Kashgar. "That's why you see so many investors coming to the city to start businesses."

Currently the largest construction project underway in Kashgar, the development is will house 100,000 people and have a shopping complex along with recreational facilities.

"I believe that Kashgar could one day catch up and even surpass the development we see in other Chinese cities," says Zhang Yunjian.

'No benefit'

Beijing believes that economic development will help ease ethnic tensions not only in Kashgar but across the remote western Chinese region of Xinjiang - one of the poorest parts in the country.

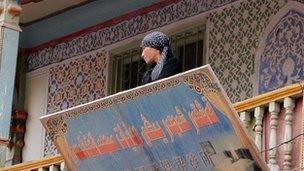

Local Uighurs worry the Chinese-style development will harm their old city

Xinjiang is home to approximately nine million Uighurs, a Turkic ethnic minority.

The Chinese authorities frequently accuse Uighurs of fomenting unrest - and some activists do want their own independent state.

In 2009, the region witnessed an explosion of ethnic violence partly fuelled by economic grievances.

In the capital, Urumqi, Uighurs clashed with Han Chinese - the majority ethnic group in China. Almost 200 people were killed.

All the development is changing the face of Kashgar and not just in terms of construction.

A decade ago the city was almost entirely Uighur but now a third of the population is Han Chinese, according to local officials.

This migration is creating a fresh set of tensions. Many Uighurs complain that they are not sharing in the economic boom. They say that most of the profits are going to Han Chinese entrepreneurs.

"We aren't really seeing any benefit from all the construction," said one Uighur, whose family have made traditional musical instruments for generations.

"Why else would they (Han Chinese) travel thousands of kilometres if they weren't profiting?"

Evidence of the tensions in Kashgar is everywhere. A fire engine sits outside the city's biggest mosque equipped with a water cannon ready to disperse any angry crowd.

In Kashgar's main square, under the watchful gaze of a six-storey-high statue of Chairman Mao, there are dozens of armed police, armoured personnel carriers, along with military trucks and vans.

Check-points ring the city where Uighurs have to get out of their vehicles to show their identity cards and sometimes be frisked.

Han Chinese tourists visiting the city travel with police escorts. Armed guards are posted at their hotels.

One Han Chinese entrepreneur in the city to scout out opportunities said he felt safe "because they are so many police on the streets."

Out with the old

Uighurs have long complained about repression under China's rule.

In July, marking the third anniversary of the riots in Urumqi, the London-based rights group Amnesty International issued a statement saying that Chinese authorities "continue to silence those speaking out on abuses" in the region.

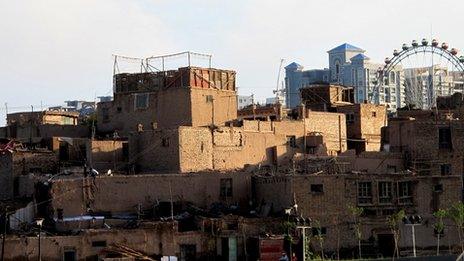

Many mud brick houses can been seen in the old part of Kashgar

Many Uighurs also say that their traditions and culture are under threat.

Nowhere is more apparent than Kashgar's historic old city, which dates back hundreds of years. Built from mud bricks, houses are piled on top of each other along a warren of paved alleyways.

For centuries, the city has stood as a symbol of Uighur identity. But now locals say that more than half of it has already been torn down and thousands of families have already left.

Many Uighurs fear that a huge part of their culture has been lost forever.

The local authorities say that the demolition is necessary because houses may collapse as Xinjiang is an earthquake zone. They are rebuilding chunks of the old city in the traditional style.

But that is of little comfort to Tursun Zunun, 53, a pottery maker in the old city. He says that his house is almost 500 years old.

"Many of my neighbours have already left," he said, sitting out his balcony, which now has a view of the city's new skyline of modern high rise office and apartment blocks.

"By the time my grand-daughter grows up all the old city might be gone."

Kashgar is a city that has long mixed traditions with trade.

But an old way of life is fast disappearing, creating a fresh source of anger among the Uighur community.

The city's economic development may not bring the stability Beijing wants.

- Published2 August 2012

- Published13 June 2012

- Published25 August 2023

- Published27 March 2012

- Published3 August 2011