Tibetan immolations: Desperation as world looks away

- Published

BBC's Damian Grammaticas has gained rare access to the region

It's sunrise and 20 degrees below zero. The sound of monks at prayer drifts across the snow-lined valley.

We are high in the jagged mountains that rise towards the Tibetan plateau. Harsh and beautiful, this region outside Tibet itself is home to six million Tibetans.

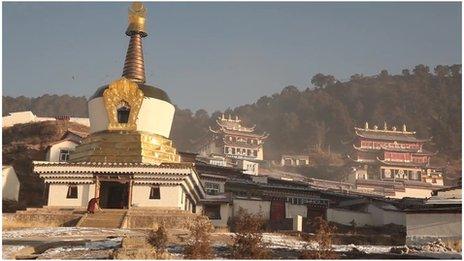

A monk is sweeping snow from the steps that lead to a small stupa. Tibetans, wrapped in blankets to keep out the cold, circle inside it, spinning prayer wheels.

Further up the hillside, a morning mist hangs over the golden roofs of the monastery behind. Scattered through these Alpine valleys, the monasteries preserve Tibet's way of life.

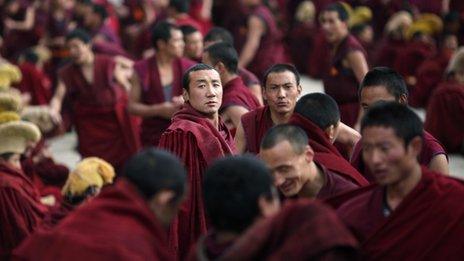

Monks in claret robes emerge from their morning devotions, while women adorned with beads circle the monastery, then prostrate themselves on the ground.

Tibetans in China are nervous of contact with foreign journalists

Since Chinese troops asserted control over Tibet more than half a century ago, and the Dalai Lama fled into exile, the number of monasteries has fallen precipitously.

And for months now, journalists have been kept out of Tibetan areas as tensions have simmered in the region.

We slipped in unnoticed. China does not want foreign interference here.

The monks we approached were nervous, China has been stepping up surveillance.

One young monk shook his head indicating he didn't want to talk; other monks waved us away or retreated into their quarters. They have good reason to be cautious.

China has been tightening its hold, not just on the monasteries, but all aspects of Tibetan life and culture.

Monasteries and stupas preserve Tibetans' way of life

Amongst Tibetans there have been growing frustrations. And there's an impression that, since the financial crisis, the outside world, and the West in particular, are not so keen to tackle China on its human rights record.

What nations want is access to China's markets and its finances.

So Tibetans have been resorting to extreme protests, setting themselves on fire. More than 120 are thought to have done so in the past three years in protest at Chinese rule in their homeland.

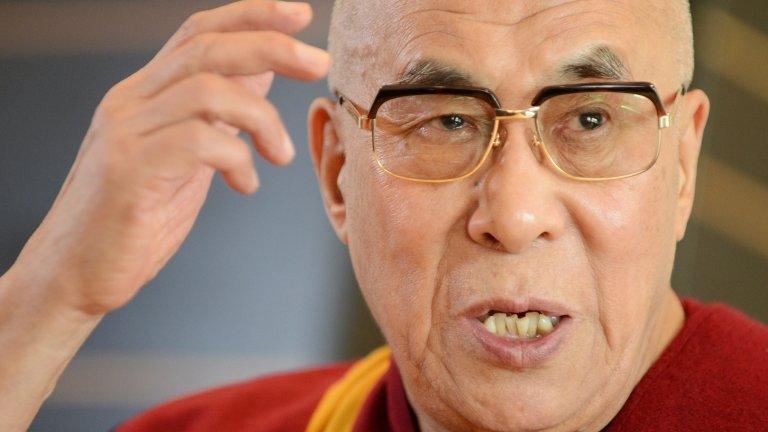

Some are said to have called for the return of the Dalai Lama as they have carried out their immolations.

Acts of desperation they may be, but China says the immolators are incited, even paid by the Dalai Lama.

Tibetans say they are discriminated against in the rest of China

Fearing widespread unrest, it has clamped down even harder, arresting and even jailing Tibetans accused of aiding those who have self-immolated.

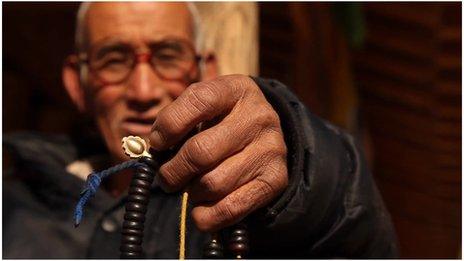

Prayer flags flutter outside the home of home of one man who took his own life. We tracked down his family, but have to keep their identity secret.

His brother told us the father of two had not received money from the Dalai Lama. The mere suggestion, he said, was insulting.

He said the authorities had been many times to question him. They wanted to know why his brother had set fire to himself, but all he could tell them was his brother was a good man acting out of conscience. Tibetans, he added, are frustrated.

"I often feel as a Tibetan I am inferior," he explained. "I feel very bad about this.

"Tibetans who go to the cities to find work are seen as darker and dirtier than other people; we're often discriminated against. I do think I am treated differently."

He insisted there had been no reprisals against his family by the authorities. But the man's father and mother were clearly nervous about talking to foreign reporters.

Many Tibetans fear that their culture is being eroded

In these bleak and windswept mountains, where herders tend the shaggy black yaks that roam the hillsides, there are few jobs for Tibetans. China says it is changing this, building roads, bringing new wealth. But development is another source of conflict.

In mid-August there was a protest in central Tibet by people worried the local environment would be damaged by mining developments. Many Tibetans feel their resources are being exploited for Chinese gain.

China's response to the protest, as to much Tibetan opposition, was harsh. Tibetan exile groups said police moved in, firing tear gas and using electric prods, to clear the demonstration.

In another village we found a woman stacking piles of straw for winter fodder for her animals. She told us there have been five or six immolations at the monastery near her home.

She did not want to give us her name but told us of the crackdowns that followed the immolations.

"We feel under pressure. There have been arrests. Police came and detained people.

"Families don't even know where their relatives have been taken."

Tibetans feel they are not listened to in China

Not far away Tibetans were circling a shrine, spinning the prayer wheels. A group of elderly ladies bowed before the building, clasping their hands. Then they lay face down reciting prayers.

After the clampdown and the media blackout, the immolations are now less frequent.

But what is not being addressed are the grievances here: Tibetans fear that they are being marginalised, their culture eroded, their voices silenced, all while the rest of the world looks away.

- Published7 February 2013

- Published9 December 2012

- Published12 November 2012

- Published6 February 2012

- Published27 January 2012