Mao Zedong remembered: China's multi-faceted deep-thinking leader

- Published

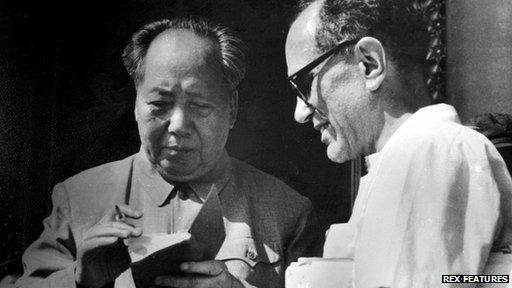

Sidney Rittenberg met Mao Zedong in the early 1970s

US citizen Sidney Rittenberg spent 35 years in China at a time of momentous upheaval, personally befriending Mao Zedong and other veteran Chinese revolutionary leaders as they seized power from the Kuomintang from 1945 onwards. Here he reveals his unique perspective on the civil war, the early days of Communism and Mao's philosophy.

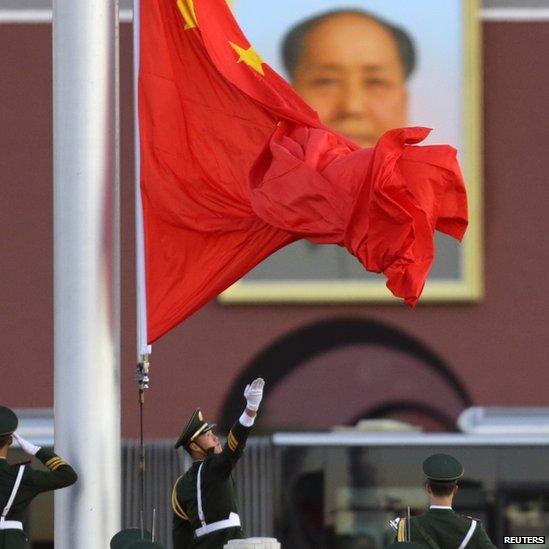

Like everything else in China, Mao's role today is a study in paradox. He is both more and less than the ginormous portrait that dominates the centre of Beijing's Tiananmen Square - and which will not be coming down anytime soon.

More, because Mao is the George Washington figure, the founder of the People's Republic of China, the great unifier of his ancient, far-flung and multifarious people.

Less, because Chinese youth today, including young Party members, typically know nothing about his writings, his doctrine, his great successes and monstrous errors.

Xi Jinping and his new leading team have warned that Soviet-style de-Maoification could lead to great confusion and weakening of the present regime - a regime whose stability they consider essential for leading China down the thorny path of reform.

Sidney Rittenberg tells Michael Bristow why he decided to join the Chinese Communist Party

At the same time, they make no bones about the catastrophic latter-day Maoist adventures like the "Great Leap Forward" of the late 1950s and the (anti-) Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976. Those megalomaniacal social experiments cost tens of millions of innocent lives.

Unlike Stalin, Mao sentenced no-one and certainly did not intend to create a terrible famine.

But he did know full well that he was engaged in huge social experiments, which disrupted the lives of multitudes - and that he himself was not sure what the outcome would be.

He confessed as much to the left-wing American writer Anna Louise Strong in 1958, when she was about to write a book acclaiming Mao's Great Leap Forward.

"Wait another five years before you write it," he told her, explaining that he was not sure yet what the outcome would be.

So is Xi reviving Maoism? Or, was disgraced former party boss in Chongqing, Bo Xilai?

Historians in China and abroad will continue to study Mao's role for centuries

The answer is "No", in both cases.

Bo was simply using demagogic egalitarian slogans to catch the fancy of the poor.

As for Xi, his reform policies run directly counter to Maoist economics, but he makes adroit use of Maoist dialectic logic to analyse China's problems and their putative solutions, and he argues for acknowledging the positive achievements of Mao's leadership.

Which leads us to the really interesting point - almost universally overlooked by Western scholars, with a few honourable exceptions, like Cambridge's Peter Nolan: Mao's analytic/synthetic philosophy is China's genuine secret weapon, although much neglected even in China today.

Take the scene when I arrived in China, September 1945.

Two rival parties, Kuomintang (KMT) Nationalists and Chinese Communists, were drawing up their armed forces, preparing to contend for power in a bloody civil war.

On the Nationalist side were well-fed, well-trained troops with air support, tank divisions, heavy artillery, motorised transportation - and out-numbering the Communists manyfold.

Mao - a multi-talented figure who gave rise to acts of great goodness and great badness - is not likely to be cast aside by the Chinese people

They controlled all major lines of communication, all major cities outside of Manchuria. They enjoyed enormous support in arms and money from the USA. Their superiority seemed absolute.

On the Communist side? In November 1946 I hiked 40km (miles) out from Yanan to meet the Communists' crack 359th Brigade, whose commander, Wang Zhen, was a friend.

The 359th had been on the legendary Long March and had forged a path all the way to southern Guangdong Province to support the building of an American airbase there in World War Two.

Meeting them as they marched towards Yanan, I was appalled by what I saw.

They were a rag-tag and bob-tailed crowd. Most of them looked like teenagers.

A few in each squad wore baste shoes, most tramped along in self-woven grass sandals. Of the 10 men in a squad, five or six would have captured Japanese rifles; the rest carried knotty clubs or red-tasseled spears.

My heart sank at the sight: How could they possibly win?

Mao's analytic/synthetic philosophy is China's genuine secret weapon, although much neglected even in China today

Yet, they did win, and quite handily at that. Why? Because of a superior, more scientific way of thinking, which led to ingenious and highly popular policies (like land reform) and to versatile tactics that clobbered the stodgy KMT officer corps.

Mao always described himself to visitors as a "primary school teacher". He was, in fact, probably the largest-scale teacher of philosophy in human history. Among his main tenets were:

Seek truth from facts. Investigate and study the facts on your specific task or locality, and base your policy and actions on that. Do not start from preconceived "truth" and amass the facts to prove yourself right, neglecting facts that cast doubt on your conclusions. In 1947 I translated a set of 40 Articles on how to carry out the land reform. Article 40 was written personally by Mao, with his big wolf-hair writing brush. It said, if any land reform workers disagree with the 40 Articles, and want to sabotage them, the most effective means of sabotage is to carry them out in your village exactly as they are written here. Do not study your local circumstances, do not adapt the decisions to local needs, do not change a thing - and they will surely fail. "No investigation, no right to speak," said Mao.

"One divides into two." Everything is many-sided, everything is in flux, nothing is pure and simple. Not analysing, not probing, assuming that "what you see is what you get" is a recipe for over-simplification and disaster. A KMT commander may be bitterly anti-Communist, but his co-ed daughter may be in the student movement and able to influence him, he may be seriously disgruntled with Chiang Kai-Shek, his secretary may be a secret Communist, He is a complex, many-sided man. Find his buttons, and push them.

The enemy far out-numbers and out-guns you? Then, only fight him in small increments, in local situations where you out-number and out-advantage him - never fight when victory is not certain. Your overall strategic position at the beginning is defensive, but each individual battle must be offensive, in order to change the balance of forces and win the war.

The Mass Line "From the masses and to the masses". The leading team should be a processing plant, gathering data on the needs and demands of people at the grass roots, formulating policies to meet those needs, returning to the grassroots to monitor the implementation of the decisions, and making the appropriate revisions. This should be a continuous "down-up-down" process of leadership. Restoring attention to this process has been a major effort of the Xi Jinping team.

Historians in China and abroad will continue to study Mao's role for centuries, but this multi-talented figure with the great good and great bad he gave rise to, is not likely to be cast aside by the Chinese people.

- Published1 July 2011