Alibaba IPO: Chairman Ma's China

- Published

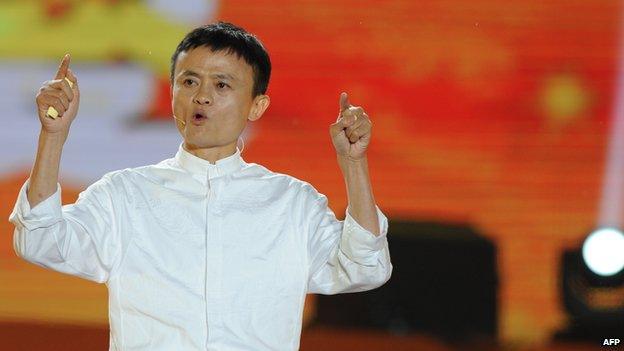

Alibaba was founded by Jack Ma in 1999 and next week will mark its stock market debut

"All of our brains are just as good." So said Alibaba's great helmsman Jack Ma to the 17 friends who made up his embryonic company in an eve of battle call to arms.

Though they might be behind the US in many ways, he told them, on the application of intelligence they could win.

The application of intelligence is where he's chosen to fight and, 15 years on, it's no longer just the original "Alipeople" listening to the thoughts of the chairman.

His is an internet company that makes a profit, bestrides the world's most dynamic e-commerce market and will next week stage one of the biggest stock market debuts in history.

Everything in China is always immense, but this is immense even by China standards. And, bigger than all the above, Chairman Ma is changing China itself.

.jpg)

Cometh the hour, cometh the man

Let's take the hour first, or the 15 years of Alibaba's young life. These years have seen the rise of middle class China and its urge to spend. It is nothing short of a consumer revolution.

China is now the biggest online market in the world. It has 600 million internet users - twice as many as the US - and half of these Chinese users already shop online.

China is also the world's biggest smartphone market at a point where Chinese shoppers are going mobile. Alibaba is therefore merely stating the obvious when its stock exchange listing documents declare: "Our business benefits from the rising spending power of Chinese consumers."

Alibaba is lucky to be surfing a giant wave. But this was not an easy wave to spot or to ride.

Who could know back in the 1990s that the internet would be one of a handful of sectors where China's one-party state would get the conditions right to produce the band of giants we see today?

Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba have all benefited from the way China has blocked international rivals from the market at the same time as encouraging competition among domestic players.

Moreover the internet was virgin territory. There were no vested interests to stifle an upstart.

And, crucially, China's internet pioneers took their cue from Silicon Valley and some of the most dynamic and innovative people in the global economy.

So the original, clever thing Jack Ma did when he gave up teaching to run his own business was to avoid the parts of the Chinese economy which hide behind the political protection racket of the one-party state and instead get involved in the internet.

Self-perpetuating success

But then he did something cleverer. Not content with mimicking the US and building "China's Google" or "China's Amazon", Jack Ma gambled that his fellow citizens would shop online if only they had the tools to do so conveniently, safely and cheaply. He went about building those tools.

For example, in China's low trust economy where sellers don't trust buyers and vice versa, Alibaba provided protection for both parties through its verification service and payments system.

Soon the original bazaar where companies sell to each other was followed by Tmall where businesses sell to the public, and then Taobao where the public sell to each other.

In gross sales, Alibaba is now bigger than eBay and Amazon combined, and its success is self-perpetuating: the bigger the network gets, the more attractive for new users to join.

The third enormously clever trick Jack Ma has pulled off is navigating the minefield of Chinese internet politics. He has convinced prickly Communist Party leaders that his business presents no threat to them.

Alibaba's IPO is expected to be the biggest internet stock offering since Facebook's in 2012

Indeed he once said bluntly: "We create value for the shareholders and the shareholders don't want us to oppose the government and go bankrupt."

But at the same time he has deftly avoided getting trapped in joint ventures with state companies, explaining Alibaba should "be in love with the government but never marry it".

Of course, not everyone admires the political compromises Alibaba has made, but through empowering a nation of shoppers and shopkeepers, Chairman Ma has certainly had an enormous impact on Chinese lives.

And the 49-year-old exam flunker who only just got into teacher training college has shown other would-be Chinese entrepreneurs that it's worth daring to dream.

In fact, Jack Ma defies many Western stereotypes of the way China does business.

He may be submissive when it comes to the politicians, but in business strategy and deal-making he is disruptive, daring, combative and tenacious.

And while some complain of an authoritarian streak and a whiff of personality cult, at least Chairman Ma can't be accused of perpetuating a faceless herd culture which stunts innovation.

Public goods

In the past decade China has gone from no billionaires to more than 300. After next week's IPO (initial public offering), Jack Ma may be worth $15bn (£9bn; 6.5bn euros). He's already promised a new charitable foundation which will be much bigger than anything China's seen before.

Alibaba accounts for 80% of all online retail sales in China

And, as he set out in an essay last year, he intends to invest time and money in tackling pollution: "Our water has become undrinkable, our food inedible, our milk poisonous and worst of all, the air in our cities is so polluted that we often cannot see the sun…People have big dreams for the future, but these dreams will be hollow if we cannot see the sun."

Jack Ma is not the only person talking about dreams.

A fortnight after the Alibaba IPO, the Chinese Communist Party will celebrate 65 years since the founding of the People's Republic, the moment when Chairman Mao declared that the Chinese people had "stood up".

Mao's successor Xi Jinping will no doubt return to his own favourite slogan, heralding the realisation of a "China dream".

Will the real China stand up?

What interests me is the divergence between the China dream that Jack Ma embodies and the authoritarian elements of President Xi's.

Some of them were on display last week, for example, in the row over election rules in Hong Kong.

In Jack Ma's China, economic choices are being liberated through the internet and the smartphone. But in the other China, the mesh of political control is growing thicker.

Alibaba has tapped into the smartphone market in China - the world's biggest

One narrative is global, confident and innovative while the other is inward-looking, defensive and xenophobic.

In its regulatory documents, Alibaba tells potential investors: "From the very beginning our founders have aspired to create a company founded by Chinese people but that belongs to the world."

Hong Kong is just such another miracle of alchemy that the Chinese people and the world wrought together, and yet Beijing insists that foreign hostile forces are trying to undermine Hong Kong's stability and use it as a bridgehead to subvert China.

Chinese people cannot be trusted to make political choices or any choices which might impinge on politics.

The two Chinas seem to exist in parallel universes.

The investors who line up in New York to invest in Alibaba will be betting on the former, the emergent consumer power set for a spending binge which will last at least another decade.

But how this increasingly competitive creative market China works with the other China of closed systems and top-down authority remains a profound and unsettling paradox.

Alibaba's coming out party only highlights China's identity crisis.

- Published6 September 2014

- Published5 September 2014

- Published27 August 2014