Confucius institute: The hard side of China's soft power

- Published

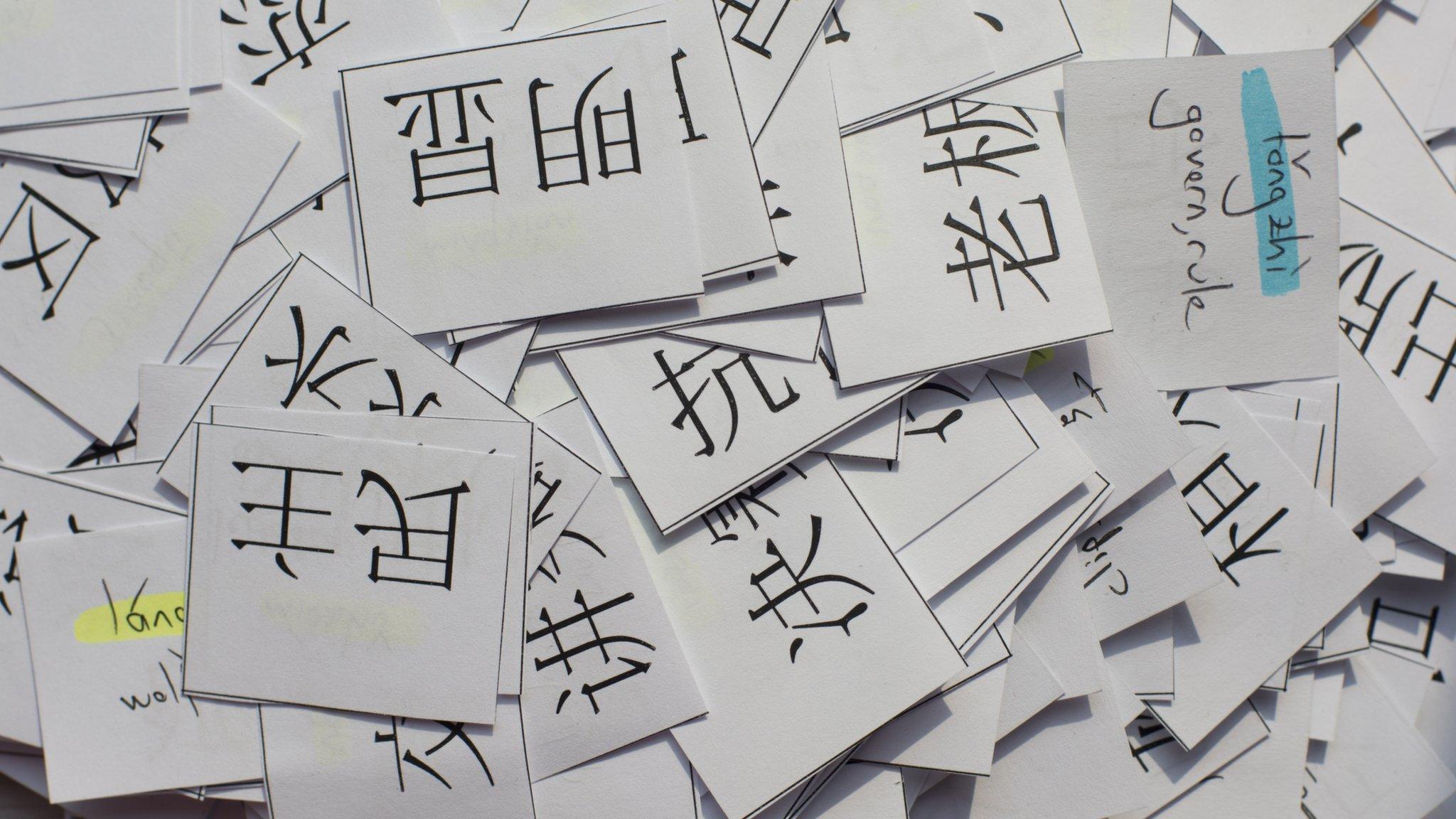

Confucius Institutes organise cultural events and classes in 123 countries

Xu Lin is an unusual kind of Chinese official.

For starters she accepted a request for a BBC interview. Admittedly she came quickly to regret it, demanding that we delete a large section of our recording.

But given that unelected Chinese officials do not need to court their own domestic media, let alone the international press, it is rare to be invited in at all. And it is even rarer to find an official who is prepared to be interviewed in English.

But Ms Xu stands out from Chinese officialdom for yet another reason.

In contrast to the caution and conformity that are hallmarks of the Communist Party system, she has found herself at the centre of a storm of controversy.

Ms Xu heads Hanban, a Chinese government-controlled agency that, on the face of it, would appear to be uncontentious. It is tasked with promoting the learning of the Chinese language overseas.

But during the 10 years that Ms Xu has been in charge, this mission has been coupled with a wider foreign policy goal - the bid to make China a cultural superpower, not just an economic one.

Paymasters

The importance of this goal is underscored by the fact that her position carries vice-minister ranking.

Since 2004, Hanban has been providing foreign universities with generous cash grants to set up language and cultural centres called Confucius Institutes.

As well as the cash, Beijing provides Chinese teachers and, at last count, Confucius Institutes have now been established on 465 university campuses in 123 countries.

The programme also reaches hundreds of secondary schools. It is a remarkable and rapid expansion of "soft power".

John Sudworth talks to Madam Xu Lin

But as the numbers have grown, so too has the concern of Western academics who believe the project presents a serious threat to freedom of thought and speech in education.

Last December the Canadian Association of University Teachers called on all universities currently hosting Confucius Institutes to cease doing so.

And in June this year the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) made the same call to US universities.

Confucius Institutes, the AAUP statement said, "function as an arm of the Chinese state" and "advance a state agenda in the recruitment and control of academic staff, the choice of curriculum, and in the restriction of debate".

The video above is a 10-minute, edited version of our interview with Ms Xu. In it, I ask her about concerns raised by Western academics.

Are the Chinese teachers in Confucius Institutes free from Communist Party control?

Does she agree that the contracts - under which China prohibits its teachers from being members of the banned spiritual organisation Falun Gong - give the party power to decide who can or cannot work on Western campuses on the grounds of religious belief?

You will not hear much about the Falun Gong movement in Chinese Institutes

And what should one of her teachers say if asked a question on a controversial topic - such as Taiwanese independence - by a student in a Confucius Institute?

China has, of course, not been deaf to the mounting criticism of the institutes, and recently state media has been rallying to their defence.

But Ms Xu's interview represents one of the most comprehensive insights to date into official thinking about the programme.

Some of her answers will undoubtedly add to the controversy, particularly the reason she gives for her certainty that her teachers are free from political control.

She has that certainty, she says, because all teachers have to write a report at the end of their postings and are questioned on their return about whether they faced politically sensitive questions from students.

To her critics, this may sound less like a neutral monitoring exercise and more like evidence of exactly the kind of political meddling she tries to disprove.

As for Falun Gong, she dismisses the concern - it is simply a matter of Chinese law, she says.

'Unacceptable' interference

In July this year, Ms Xu herself became the subject of controversy when she and her staff attended an academic conference in Portugal.

Her organisation was among the sponsors of the event but, on arrival, Ms Xu discovered that the programme contained publicity for a Taiwanese educational organisation, another sponsor.

Arguing that such a reference was "political" Ms Xu ordered her staff to remove the programmes and take them to the home of a teacher working at a Confucius Institute.

After frantic negotiations with conference organisers the programmes were eventually returned with four pages removed.

Chinese officials insist Confucius Institutes are free of political interference

The conference president, Roger Greatrex, issued a statement, external calling the "interference" in the activities of an independent academic organisation "totally unacceptable".

Ms Xu objects strongly to my having raised the issue of the Portugal conference, as it was not, she points out, on the list of topics submitted in advance.

After we had finished the recording, along with her deputy and her press officers, she kept us for well over an hour, insisting that she had been misled into agreeing to the interview and demanding that we erase, there and then, the section about Portugal.

It is common practice for media organisations to be asked to provide a list of questions when seeking interviews in China.

But the BBC makes clear, as we did in this case, that while we are happy to give an outline of the general topics to be discussed, we do not give specific questions in advance.

The version of events given by Ms Xu in our interview differs strikingly from Mr Greatrex's and represents an important on-the-record account of an issue of public interest.

We refused to delete our tape.

Welcome cash

The Western defenders of Confucius Institutes argue that they are primarily language training centres, so there is little room for Beijing to use them to brainwash foreign students.

In addition, the benefits are enormous in that they offer access to Chinese language learning that cash-strapped universities simply could not afford on their own.

The generous sponsorship from the Chinese government is no different, they suggest, from the myriad other partnerships - both corporate and government - that are now part of the fabric of the modern academic world.

We now have a first-hand defence of the project from China itself.

China's Confucius Institutes should be judged on how they operate in practice, Ms Xu tells me, not by reference to abstract principles.

And yet what if, in practice, that hypothetical student in the back of the language class ever does put up his hand to ask about Taiwanese independence?

"Every mainland teacher we send," she tells me, "all of them will say Taiwan belongs to China. We should have one China. No hesitation."

- Published6 June 2014

- Published25 May 2012

- Published11 September 2012