China's black market for organ donations

- Published

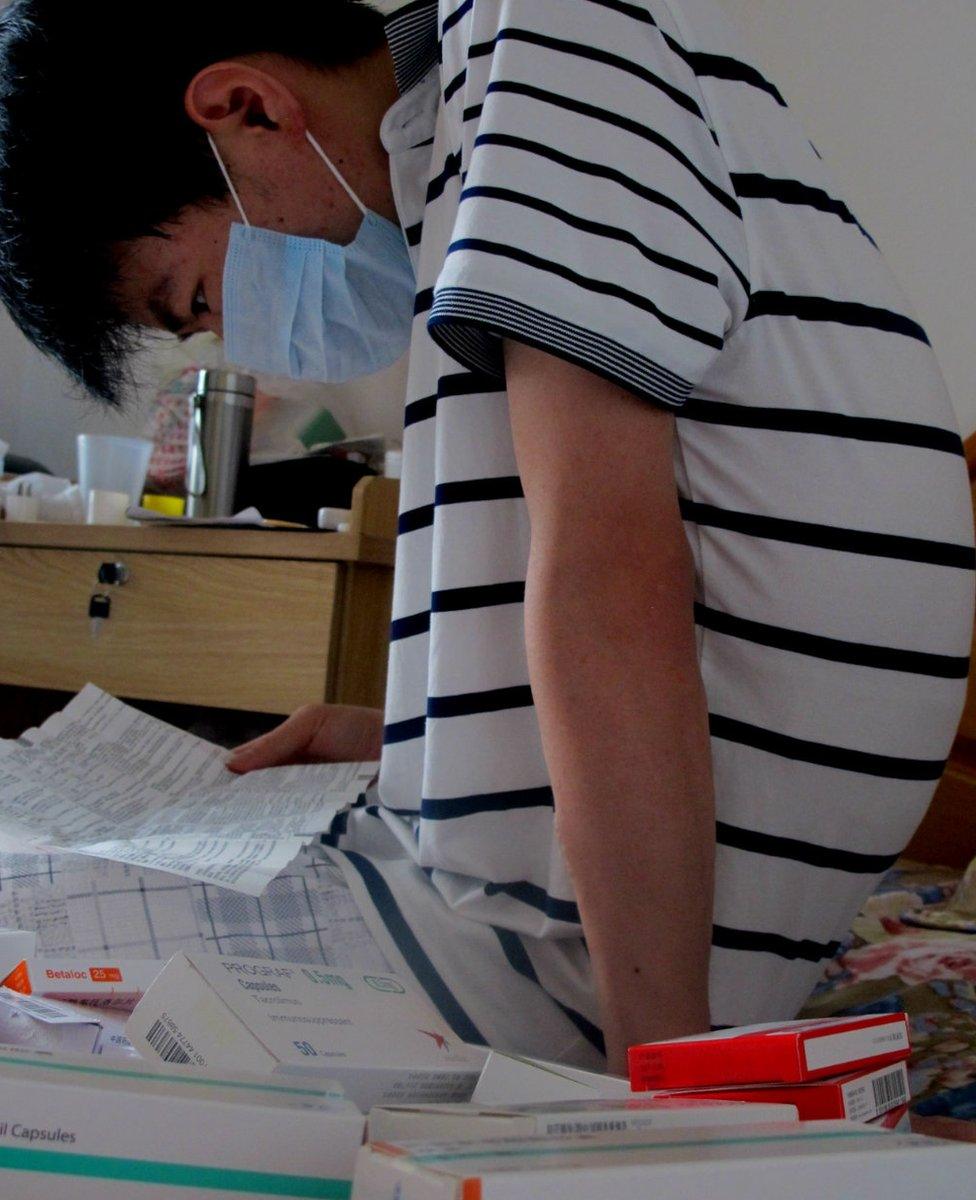

Lian Ronghua says she doesn't known why her sons are ill, but she could not save them both herself

It is the unimaginable decision that no mother should ever have to make: choosing which of her sons might live or die.

That was the choice Lian Ronghua, 51, faced earlier this year.

Both her sons were suffering from uraemia - a condition that leads to kidney failure. But only one of them could receive their mother's organ. Their father suffers from high blood pressure and could not donate.

In the family's small rented apartment, Ms Lian struggles to talk about that time.

"I don't know why both my sons are ill," she told me, tears streaming down her face.

Li Haiqing said he still hoped he would one day receive a kidney

In the end, the decision was taken for her. Her eldest son, Li Haiqing, 26, decided his 24-year-old younger brother, Haisong, should get their mother's transplant.

"I wanted to give my brother the kidney as he's younger and has a better chance of recovery," said Haiqing, who was forced to give up his medical studies because of his illness.

"Of course I hope I get a kidney before it's too late. But if I don't, I'll just need to keep on doing dialysis."

One 21-year-old man sold his kidney for £4,000: "I was blindfolded and driven to a small farmhouse... I woke up and my kidney was gone"

But his chances of getting a transplant are slim - China suffers from a huge organ shortage.

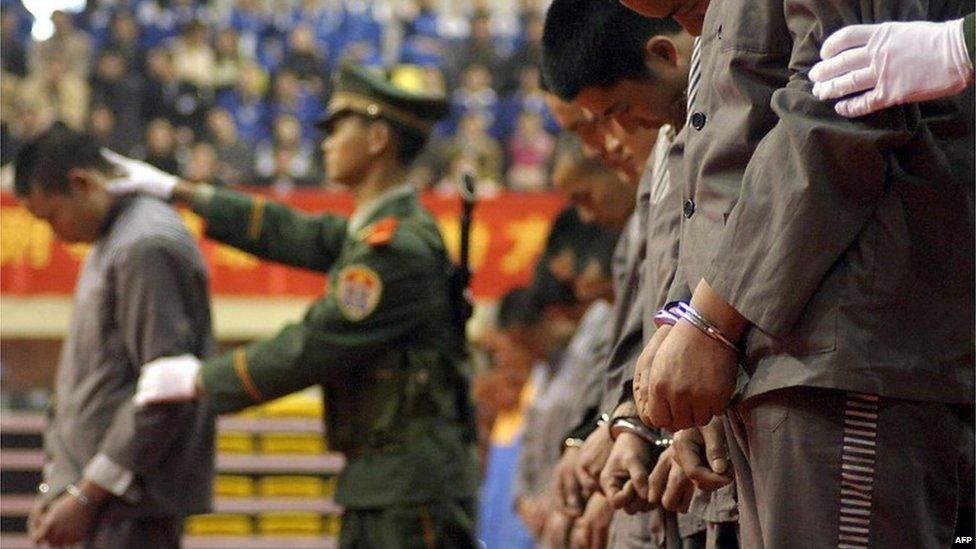

For years it harvested the organs of executed prisoners to help meet demand.

Following international condemnation, Beijing says it ended the practice at the start of this year - although officials admit it will be tough to ensure compliance.

Now the government says it will only rely on public donations.

China used to remove organs from executed prisoners for transplants, a practice which was widely condemned

It set up a national organ bank which in theory is supposed to distribute organs to those who are the best match and most in need.

But critics say that the system is open to abuse and those with connections will be able to jump the queue.

Perhaps the biggest problem confronting the government is persuading the public to donate in the first place.

Many Chinese believe the body is sacred and should be buried intact in a show of respect to their ancestors.

Largely for this reason the country's donor rates are among the lowest in the world - 0.6 donations per million people compared with 37 per million in Spain.

'My kidney was gone'

The government says that more than 12,000 transplants will be carried out this year - an increase on the number of operations carried out when it used prisoners' organs.

But with an estimated 300,000 people requiring organs, the huge demand has created a thriving black market.

One man told the BBC he was operated on at a farmhouse he was driven to blindfolded

After weeks of investigation, a young man who sold his kidney agreed to speak to me as long as we protected his identity.

Lifting up his T-shirt, he showed me the tell-tale surgical scar where his organ was removed.

The 21-year-old says he sold his kidney for $7,000 (£4,500) to pay off his gambling debts.

He describes the dark, secretive world where the traffickers operate after arranging the sale online.

"At first I was taken to a hospital where they collected blood samples and carried out check-ups," he told me.

"I then waited at a hotel for several weeks until the traffickers found a match.

"Then one day a car came to pick me up. The driver told me to put on a blindfold. We drove for around half an hour along a bumpy road.

"When I took my blindfold off I realised I was at a farmhouse. Inside there was a full surgical theatre. There were doctors and nurses in uniforms.

"The woman receiving my kidney was there with her family. We didn't speak.

"I was scared but then the doctors put me to sleep. I woke up in a different farmhouse - my kidney was gone.

"The buyer wanted life and I wanted money."

It's an extraordinary account that we cannot independently verify.

Li Haisong's life is on hold while he waits for an donor who may never arrive

But it lifts the lid on this lucrative illicit trade where the traffickers use military-style tactics to keep it hidden in the shadows.

One of those who will not be buying an illegal organ is Li Haiqing, whose younger brother received their mother's kidney.

He is desperate for a transplant but says he will only accept a legally obtained kidney.

While he waits for a life-saving operation, he needs to go the hospital three times a week for dialysis.

His life is on hold. He hopes to one day build a successful business but that dream may never happen.

Like many others here, he fears he will die before ever getting a transplant.

- Published4 December 2014