The politics behind China's stock market turbulence

- Published

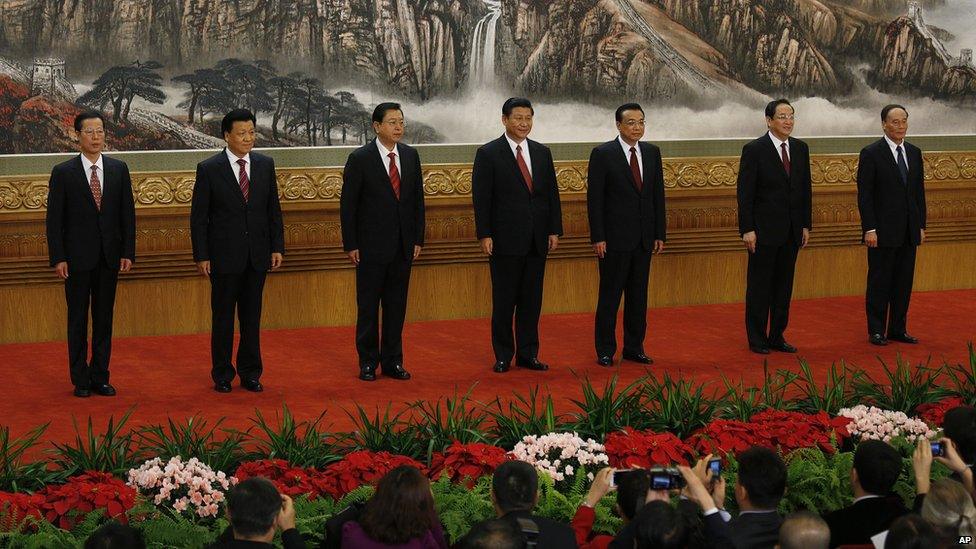

Presenting a public united front is key to the Communist Party

One of the most extraordinary things about the world's number two economy is that when it faces a crisis, the leadership carries on in public as if nothing has happened.

Decisions which affect the fate not just of 1.4 billion people in China but as we now know, the rest of the world as well, are made in secret by a handful of men.

This week, China's top political leaders have made no mention of the crisis, flagship mainstream media avoided touching on it, and government censors constrained discussion on social media within firm boundaries.

'New normal'

Does this matter? It is certainly different from any other major economy where the causes of such a crisis and competing solutions would have been thrashed out day in day out for the past two months.

Stepping back from the stock market turmoil, the central challenge for China's policy makers is whether they can build a prosperous advanced economy with sustainable long term growth before the old-style investment driven economy grinds to a zero growth catastrophe.

Mr Qi has lost £40,000 ($60,000) in shares after investing £100,000 in May

The government has loudly committed itself to a "new normal" which necessitates a range of painful but unavoidable market reforms. But no large authoritarian country has ever managed the move to high income status. So if China did achieve such a feat, it would be setting a precedent and making history.

Not for the first time, Party members and many other Chinese citizens may well retort, adding that China's leadership deserves credit for its management of the economy over the past three decades of reform. But the stock market crisis has demonstrated that the way Chinese politics relates to its economics has very specific consequences and not all of them are beneficial.

First is the need to find scapegoats. Because of leadership paranoia about anything which approaches criticism of China's political system, when things go wrong there has to be a villain and that villain has to be identified quickly and publicly.

So this week has seen a number of high profile investigations of market manipulation as well as the detention of a financial journalist for allegedly "fabricating rumours" which is often shorthand for facts which happen to be politically inconvenient.

Wise and fair?

But it is a matter of public record that government, central bank, regulators and propaganda chiefs all boosted the bull market in the early part of this year, and in any other economy, there would now be a discussion about the performance of each of them.

Was it wise to pour leveraged funds into such an inexperienced market at such an astonishing rate? Was it well-judged to deflate a credit bubble by creating a stocks bubble? Was it fair to make small investors feel paper-rich in an effort to get them to save less and spend more?

China has been keen to boost consumption

Instead of targeting a handful of brokers for insider trading, a different politics would allow questions about the systemic corruption risks on the markets and about how to make the regulator independent and transparent. TV news bulletins might hear from Chinese citizens who've lost their savings and have their own views on who is responsible.

The taboos about touching on anything systemic, anything relating to transparency or vested interests make it hard to have a rational discussion about what caused the problem or how to put it right.

A second feature specific to Chinese politics in a crisis is the determination not to let the facts get in the way of the preordained script and to reinforce unity around that script.

Throughout the stock market plunge, the main evening news programme on national TV has focused on anything but, typically leading with long reports on political leaders appearing together at various work forums and making encouraging speeches with no reference to the elephant in the room. A public united front is an article of faith for the Communist Party.

China's economic slowdown

282%

China's debt to GDP ratio

$28 trillion

Debt has quadrupled since 2007

-

0.25% cut in key lending rate

-

5th interest rate cut since November

-

7% China's growth target for 2015

In the mid-1980s, divisions at the top over how to confront economic problems played a part in events leading to the student democracy protests of 1989. Many in the leadership still blame those divisions for the massacre which followed. "United we stand, divided we fall" is a Chinese Communist Party tenet of faith.

Due to the enormous secrecy of Chinese, it's impossible to know exactly what's going on, but there are signs of serious divisions. The bungled stock market intervention of early July was a clear departure from the market reform agenda that Premier Li Keqiang had set out at the beginning of the year.

A fortnight ago, an important commentary in the flagship People's Daily criticised retired officials "who continue to use their influence to intervene in crucial decisions long after they have retired". And earlier in the year the same Party mouthpiece launched a broadside against factions, pointing out that throughout Chinese history, factional politics had brought down many mighty dynasties.

The finance minister Lou Jiwei issued a blunt warning recently: "We don't have a lot of time left and the only way forward is reform." He was not talking to you or me.

Don't forget the context for decision making here. Even before the economic woes of the summer, the anti-corruption campaign had turned elite politics into a blood sport in which many top politicians, bureaucrats and generals found themselves behind bars.

The harder the Party works at public displays of unity, the harder it is to believe in that unity.

Some of the country's most powerful families have been hurt in the anti-corruption campaign and the market reforms ahead will hurt their business empires further. The stock market crisis and the handling of this month's currency devaluation have damaged the credibility of economic policy makers at a time when the sapping of confidence in China's growth prospects make decisions about how to handle long term reform even more critical.

The absence of public discourse produces a parallel universe with political and business elites awash with rumours about factional vendettas and power plays.

Underlying all else is the knowledge that China has reached an important moment of decision. When the economy was growing fast, there were no hard choices between core economic and political objectives.

China has experienced immense economic growth over the past three decades

But now that growth is slowing, the conflict is stark between the economic imperative of freeing up markets for the sake of China's future and the political imperative of iron control for Party survival.

Yes the Party wants markets because it knows they will allocate resources more efficiently than the state, but when the chips are down it wants total political control more because it fears that anything less will challenge its rule.

Behind the walls of the leaders' compound in Zhongnanhai, there are many views on how to square that circle on any given day for any given policy decision. But the constituency fighting for independent regulators, transparent markets and brave financial journalism is not strong.

Now that the mesmerising stock market bubble has burst, those outside Chinese borders will mull the fundamental question about whether China can build an innovative market economy under a brittle one party state. But that is a question that those inside China are not invited to debate.