Can UK be China's best partner in the West?

- Published

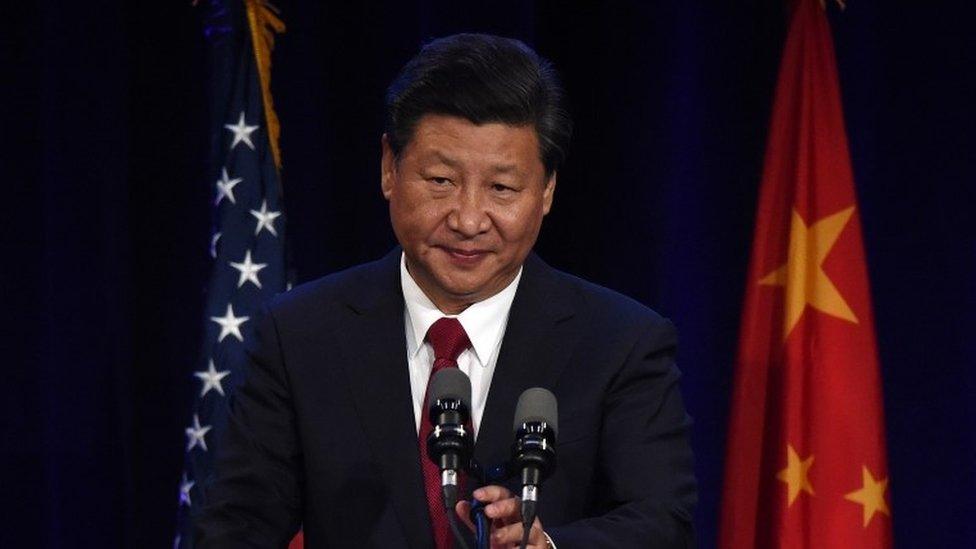

China's Xi Jinping has kick-started his first state visit to the US

Many governments hedge on China. Who, after all, can predict what is going to happen in such a vast and complicated country as it endures the birth pains of modernity and attempts to marry markets with one-party rule and find a fitting place in the international order?

So from Washington to Tokyo, Berlin to Singapore, governments hedge, hoping for the best in China but preparing for outcomes less than the best.

Not the British government. Not any more.

Chancellor George Osborne said he rejects such thinking. Britain wants to be China's "best partner in the west".

"We want a golden relationship with China that will help foster a golden decade for this country."

The tone is particularly striking when set against the blunt language coming from Washington in the lead-up to President Xi Jinping's US state visit this week.

The US wants China to follow common rules in cyberspace

Of China's record on cyber hacking, US President Barack Obama said: "There comes a point at which we consider this a core national security threat. We can choose to make this an area of competition, which I guarantee you we'll win if we have to."

The strategy of engagement with China has lasted through eight presidents since Richard Nixon in 1971.

But it is now under intense scrutiny across the board, with companies complaining that they are being squeezed out of Chinese markets and Republican presidential candidates railing against China for trying to "steal American jobs" and "undermine US interests".

Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump has spoken out publicly against China

'Constant accommodation' of Beijing?

Washington has noticed the difference in tone.

When Mr Osborne rushed to sign the UK up as a founder member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, unnamed American officials complained of London's "constant accommodation" of Beijing.

This month, the Chinese Communist Party Propaganda Department directed all media outlets to "promote the discourse on China's bright economic future and the superiority of China's system".

Mr Osborne has helped by giving Beijing face, at least on the first part.

"The growth in the Chinese economy will be more than the entire British economy at least in the coming five years.

"Even as China's growth slows, it will continue to be a powerhouse for the global economy. There will be many new opportunities for the UK."

Mr Osborne has been in China to promote relations with Britain

All of this is true of course. But it is not a complete picture.

For all its great strengths and magnificent achievements, China's economy remains very complicated with contradictory government impulses to liberate and to control.

As for the spin on the superiority of the Chinese system, until recently, Mr Osborne's hosts needed no reassurance from foreigners on that score.

Having weathered the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 and the global financial crisis a decade later, they prided themselves on a reputation for unshakable confidence and competence.

China, it seemed, had miraculously avoided the cyclical economic and electoral shocks to which more earthbound economies were vulnerable.

China's "Black Monday" triggered a global rout

The fading Chinese dream?

But after this summer's carnage on the stock market and mishandled currency devaluation, that particular China dream is fading.

The painful growth slowdown Beijing has long warned of, is upon it and in some ways worse than it feared.

So China's leaders look mortal and their system less superior.

While the Chinese economy is still upbeat about all the positive things Mr Osborne has talked about on his trip, it is still a middle income country with fragile economic institutions, unaccountable politics and protected markets.

Even some of the long-promised reform agenda is looking vulnerable.

But Mr Osborne's determination not to hedge on any of this has produced some striking outcomes which set the UK apart from its European and American allies.

It is unimaginable, for example, that the United States would consider letting China design, build and operate a nuclear power station on US soil.

The UK will be the first Western government to do so.

A sign marks the site where the Hinkley nuclear power station will be constructed

The £2bn deal will enable greater collaboration on nuclear plants between Britain and China

Quite apart from the safety questions, Washington would have national security objections about involving China in its critical national infrastructure.

Of course, the United States and China are strategic rivals in Asia in a way which Britain and China are not.

'Security concerns'

But until recently, Britain's intelligence agency MI5 was complaining loudly of Chinese attempts "to steal our sensitive technology on civilian and military projects".

Of course, China has its own security concerns.

In the wake of the Snowden revelations of massive American surveillance programmes, China began work to remove its dependence on foreign telecoms technology and new national security legislation is likely to make it even harder for outsiders in sectors with a security dimension.

And on China's definition of national security, that means many of the most profitable and fast growing parts of the economy.

What's more, Beijing would not consider allowing another country to build a nuclear power station or any other key infrastructure on Chinese territory.

And Britain is currently barred from sectors where it is strong, like financial services, IT, media and healthcare.

All of which will make it hard for Mr Osborne to reach his goal is to make China Britain's second largest trading partner by the end of the decade.

We won't be likely to see the Dalai Lama back in Downing Street anytime soon

And meanwhile the process of trying will close down other aspects of UK China policy.

Put simply, there can be no stellar exports and no "golden era" if senior members of the British government do things which irritate Beijing.

So do not expect to see the Dalai Lama in Downing St between now and 2020.

And do not expect to hear a robust defence of the political rights of Hong Kong's citizens from London.

- Published23 September 2015

- Published21 September 2015

- Published21 September 2015

- Published12 September 2015