The night time 'McRefugees' of Hong Kong

- Published

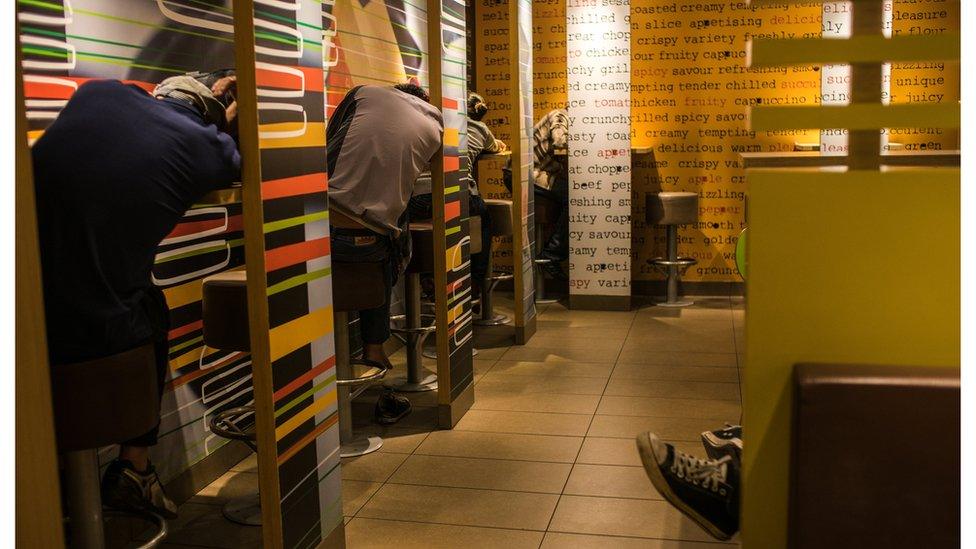

Earlier this month, an elderly homeless woman died in a crowded Hong Kong McDonald's restaurant. No-one noticed her for seven hours. The BBC's Juliana Liu spent a night in one 24-hour restaurant to meet the people the city has dubbed "McRefugees".

On a major road in the working class neighbourhood of Sham Shui Po, a pair of bright yellow arches beckons visitors into a 24-hour McDonald's outlet.

Spread out over two floors, it is spacious by Hong Kong standards.

As night falls, the fast-food restaurant becomes a temporary hostel, attracting dozens of the city's poorest people.

Although similar crowds can be found at McDonald's outlets all over Asia - especially in Japan and mainland China - an aging population, unaffordable property prices and stagnant wages all conspire to make the problem particularly acute in Hong Kong.

Here, it is a vibrant community of regulars, many of them elderly, whose cheerful smiles mask desperately sad stories of personal misfortune.

The unofficial leader of the group is Ah Chan, 54, a well-spoken former police officer.

He says he rents a tiny room nearby, but spends most of his evenings at McDonald's, where he can while away the hours in comfort chatting with friends.

"This is a familiar place, with familiar faces," he tells me in fluent English. "These people are all wanderers. Some come for a short while, others a long time. Most of them don't have a home. They have nowhere else to go."

Like some others there, Mr Chan comes for the company and because the restaurant is nicer than his home

Hong Kong is one of the world's most unequal places in terms of wealth distribution. About one in five of the territory's seven million people live in poverty, according to government figures.

Among the elderly, one in three lives below the poverty line.

At a recent conference on the subject, officials said the best way to tackle poverty was to expand the economy and create jobs.

But this strategy is unlikely to help Mr Chan. Over a paper cup of tap water, he explains his own slide into downward mobility.

After university in the late 1970s, he joined the police department, leaving in 1996 to start a business investing in mainland China.

Over the next seven years, he poured most of his savings, and money from his relatives, into the company. But in 2003, his mainland Chinese partners ran away with the money, he said.

After three years of legal battles, he returned to Hong Kong in 2006, broke and exhausted.

"What happened in China defeated my mind," he says. "I had to take a rest to ease my mind. I'm trying to face what's in front of me. Sometimes, I feel very tough. Other times, the bad memories will influence me."

Mr Chan says he rarely sees his relatives: "I can't face them. They trusted me, and I let them down. I can't say I had no responsibility for what happened."

He does casual jobs to make spending money. He also frequents food banks and wears donated clothing.

The view from the other side of the lens

Indian photographer Suraj Katra began photographing Hong Kong's "McRefugees" in 2013, beginning a project to document what he called a "social phenomenon".

"As a photographer, I found it so ironic that you have such colourful ambience in the background and then these old homeless or poor people in the foreground. I snapped a few photos on my phone.

"I always looked at McDonald's as amazing value in a place like Hong Kong. You get cheap food, good lighting, good air conditioning, good seating and good service. I thought I should document the people who were really making the most of this.

"I come from a much poorer country, India. For me, when I look at these people, I still think they are well-off compared with the homeless in a place like India. It's more organised. At least there is some welfare and a place to sleep."

As we chat, well after midnight, two elderly people snore loudly on the immediate benches near us.

A staff member comes over to explain that someone has locked himself into the bathroom, but otherwise leaves us alone.

In a statement later, McDonalds said it "welcome all walks of life to visit our restaurants any time". It expressed sadness over the recent death, and said it balanced being "more accommodating and caring" to people staying there overnight with ensuring a good experience for all customers.

'You must think I am very lazy'

By this time of night, all the paying patrons have left. Only the "McRefugees" are left.

David Ho has struggled to get work after suffering a stroke

One of them is David Ho, 66, who until last year worked as a security guard on a monthly salary of HK$10,000 ($1,300; £840). But he suffered a stroke, rendering him unable to work.

He survives on a daily cocktail of medicines, which he gets from a public hospital, and a monthly government welfare payment of HK$3,870.

"You must think I am very lazy. But I am not. I want to work. But I can't find a job at my age. That is why I am taking money from the government," he says.

Even with welfare, Mr Ho cannot afford to live in Hong Kong, which has some of the most expensive property in the world.

The city does provide public housing, but there is a shortage of units and the waiting list is years long.

So, he rents a room across the border in Shenzhen for 1,000 yuan (HK$1,222; $157; £103) a month.

Mr Ho misses Hong Kong, so he travels on the train to the Sham Shui Po McDonalds once a week or so, staying for a few days at a time.

As we chat, a steady stream of people continue to arrive, well into the morning hours.

A middle-aged man comes in and sits down just behind us. He listens intently and repeats, parrot-like, everything we say.

By this time, the lights on the second floor, where we have been gathering, are lowered.

Nearly everyone has gone to sleep.

- Published7 January