Enforcing family care by law in Shanghai

- Published

China's one-child policy has created a unique set of circumstances

The stairs are steep, very steep. It's best to walk slightly sideways coming down. And you have to watch your head either way.

Two floors up, you emerge into a small room with a big hospital bed, and in it is Yao Jainguo's mother in law. She's in her early 80s. She's been confined to this space for more than 20 years after a nasty fall.

Mr Yao and his wife care for her 24/7. One does the night shift, the other the day. They have help from a volunteer group who visit, and there is some government assistance too.

But it is them - and the porter they hire - that carry her down the steep stairs a few times a year for a trip somewhere nice in Shanghai.

The Shanghai government fears that level of commitment is fading.

It fears the demise of the proud Chinese tradition of filial piety. It fears that a richer generation of children, whose lives are dominated more by their work, will be less inclined to look after their ageing parents.

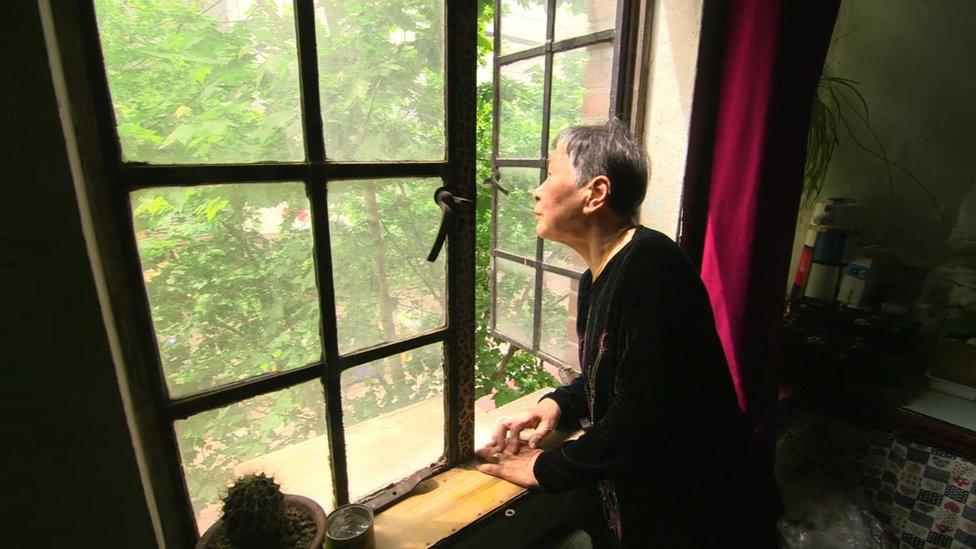

Previous generations had no doubt that they would be cared for by loved ones later in life

Shanghai is a vast metropolis. Among its 24 million people is the highest proportion of pensioners of any city in China.

Officials here think part of the answer is to force people to care.

It's introduced a punishment that strikes at the heart of every Chinese consumer - their credit score.

It's a tool the state uses to deal with a range of wrongdoing: even traffic offences can lead to a worsening credit score.

New rules implemented this month extend a 2013 law which gave elderly parents the right to sue their neglectful children in the courts. Shanghai now has the power to punish the worst offenders by downgrading their credit score.

"If the behaviour is harming old people, if it goes past the legal threshold, and if the old people sue and complain about it, then the behaviour will be punished under the law," said Ying Zhigao from the city's Bureau of Civil Affairs.

He said this wasn't a measure aimed at dealing with the ticking time bomb of social care provision in a country where the population is ageing fast.

"We are building on a very strong Chinese tradition of respecting and caring for old people" he said.

Development has lifted millions of Chinese people out of poverty, but has also weakened social bonds

But there is the issue of who will pay.

An ageing population is an issue that much of the world is trying to grapple with. But China has a unique contributory factor: the one-child policy.

The decades old restriction, which has just been removed, means there are fewer children to do the caring.

Mr Yao sees changing attitudes too.

"I think the young generation has a different kind of thinking" he said. "In the future it's going to be an impossible situation in Shanghai because only one child in the future will be part of a young couple who are looking after four old people."

"That's a lot to ask," he said, adding he was speaking from the bottom of his heart.

In Fujian Province, one temple also acts as a nursing home for older people, many of whose children have moved away

Ju Higun was quick to show us the black and white photograph of his son inside the folder where he keeps all his government documents.

Inside his one room home on the ground floor of an old house which accommodates 70 people, he and his wife insisted on handing out ice cream to us as we spoke.

Mr Ju doesn't have a bath and he shares a grubby kitchen. He walks with his wife to the local government care centre down the road, where he gets food and has a wash every day.

The couple see their son once or twice a month. The expansion of Shanghai's metro network has made it easier he says.

His son also sends money. Mr Ju whips out an envelope and fans out the handful of red 100 yuan ($15; £10) notes inside. It goes under the pillow in an instant.

Does he miss his boy? Yes he does.

He said he wishes they lived together, as three generations of some Chinese families still do, so they could care for each other, like families in this country used to.

- Published21 December 2015

- Published26 October 2015

- Published29 October 2015

- Published29 October 2015