China to end one-child policy and allow two

- Published

The end of China's one-child policy explained

China has decided to end its decades-long one-child policy, the state-run Xinhua news agency reports.

Couples will now be allowed to have two children, it said, citing a statement from the Communist Party.

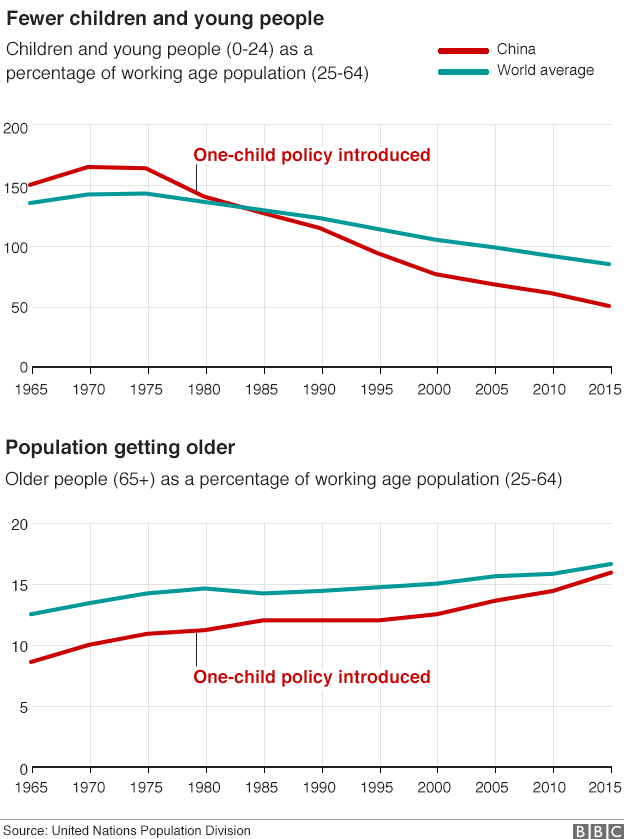

The controversial policy was introduced nationally in 1979, to slow the population growth rate.

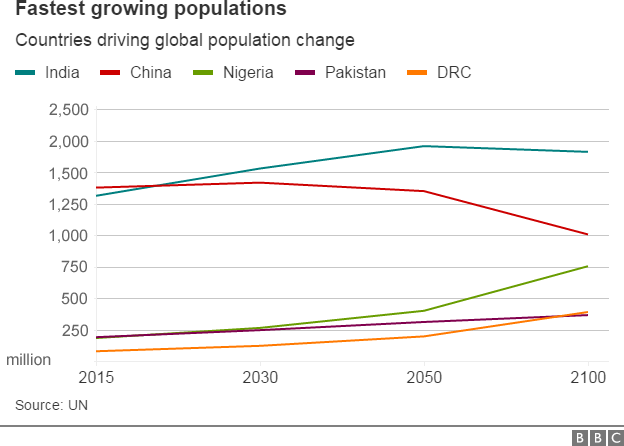

It is estimated to have prevented about 400 million births. However concerns at China's ageing population led to pressure for change.

Couples who violated the one-child policy faced a variety of punishments, from fines and the loss of employment to forced abortions.

Over time, the policy has been relaxed in some provinces, as demographers and sociologists raised concerns about rising social costs and falling worker numbers.

The decision to allow families to have two children was designed "to improve the balanced development of population'' and to deal with an aging population, according to the statement from the Community Party's Central Committee carried by the official Xinhua News Agency, external (in Chinese) on Thursday.

Currently about 30% of China's population is over the age of 50. The total population of the country is around 1.36 billion.

The Communist Party began formally relaxing national rules two years ago, allowing couples in which at least one of the pair is an only child to have a second child.

China's one-child policy

John Sudworth examines the painful legacy of China's one-child policy

Introduced in 1979, the policy meant that many Chinese citizens - around a third, external, China claimed in 2007 - could not have a second child without incurring a fine

In rural areas, families were allowed to have two children if the first was a girl

Other exceptions included ethnic minorities and - since 2013 - couples where at least one was a single child

Campaigners say the policy led to forced abortions, female infanticide, and the under-reporting of female births

It was also implicated as a cause of China's gender imbalance

Correspondents say that despite the relaxation of the rules, many couples may opt to only have one child, as one-child families have become the social norm.

Critics say that even a two-child policy will not boost the birth rate enough, the BBC's John Sudworth reports.

And for those women who want more than two children, nor will it end the state's insistence on the right to control their fertility, he adds.

"As long as the quotas and system of surveillance remains, women still do not enjoy reproductive rights," Maya Wang of Human Rights Watch told AFP.

I lost two siblings - by Juliana Liu, BBC News Hong Kong correspondent

The BBC's Juliana Liu, pictured with her family

I was born in 1979, the year the one-child policy was implemented. And even then, I wasn't supposed to be born.

In my parents' work unit, there were also quotas for babies. By the time my mother announced her pregnancy, the quotas were all used up for the year.

But kind-hearted officials decided to look the other way and allowed my birth. My would-be siblings were less lucky.

As a result of the policy, my mother had to endure two abortions. Even today, she talks about 'Number Two' and 'Number Three' and what they might have been like.

Writing in The Conversation, external, Stuart Gietel-Basten, associate professor of social policy at the University of Oxford, says the reform with do little to change China's population and is instead a "pragmatic response to an unpopular policy that made no sense".

The announcement in China came on the final day of a summit of the Communist Party's policy-making Central Committee, known as the fifth plenum.

The party also announced growth targets and its next five year plan.