China: Xinjiang government to 'clear up' ethnic names

- Published

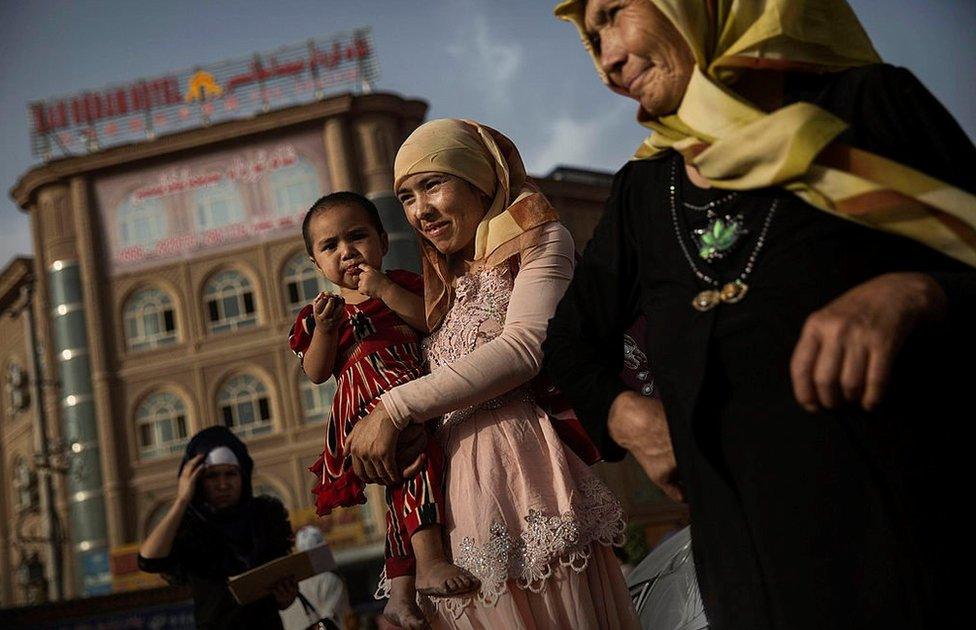

Some groups see the move to formalise names as a way of undermining their ethnic identity

Authorities in China's Xinjiang region have announced their intentions to "clear up" inconsistencies in the names of people from various ethnic groups by the end of the year.

According to recent official media reports, the vice chairman of Xinjiang's regional government, Zhu Changjie, recently told reporters that "the government is trying to develop a standardised system to input minority members' names".

Uighur, Kazakh and Tibetan minorities often have problems inputting their names on to official documents, which are built around accommodating short, Mandarin names - often no longer than three Chinese characters, or ten Latin alphabet characters.

The new regulations seek to erase inconsistencies on identity and social security cards, and in medical insurance and education records, but may antagonise ethnic minority groups that see the move as a form of undermining their ethnic identity.

'National unity'

Popular news website The Paper said that moves, including standardising minority names, were being implemented following an "important speech" by President Xi Jinping in December 2015 on the need for national unity.

Government mouthpiece the People's Daily said on 3 July that 27 initiatives were being introduced at regional level in Xinjiang.

Some 45% of Xinjiang's population are Uighur

The paper said these would help address "outstanding problems over the years in reflecting groups of ethnic minorities".

Over half of Xinjiang's population are Uighur or Kazakh. Another 40% are Han Chinese.

China Daily said that this "problem has only become more significant in recent years as use of the internet and e-commerce took off in China".

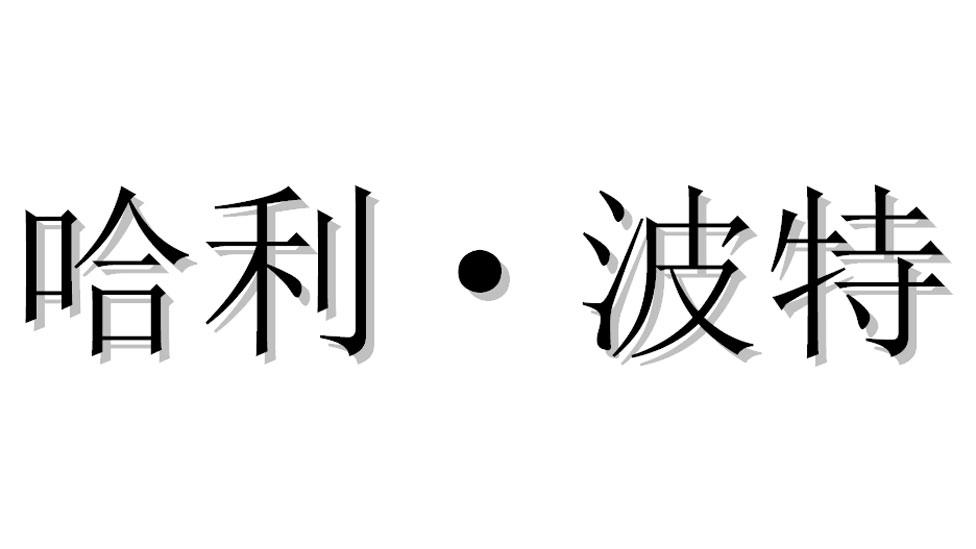

An interpunct separates first and second Latin alphabet names - here spelling "Harry Potter"

In 2011, Bank of China branches introduced a standardised format for users with ethnic names to input what is known as an interpunct or a middle dot, a punctuation mark that distinguishes long surnames and given names.

Most people across China do not require the middle dot, as their names are no longer than three characters.

Other banks and services have been slow to introduce this, leading to calls for a standardised input format for ethnic names earlier this year.

In February, China Daily quoted Xu Taizhi, head of the Xinjiang population management bureau, as saying that across China "many e-commerce developers know little about ethnic names and the format of the dot used in ID card registration."

"Some platforms don't even include the dot in their input system, which has created problems for users who need to verify their ID when trying to use online services," he said.

'Corrected names'

Without being able to rely on e-commerce company mechanisms, the Xinjiang government has already taken steps towards changing ethnic names on official documents.

A Uighur woman holds ID cards at a protest in Xinjiang Uighur autonomous region, China

According to US-funded Radio Free Asia, "the authorities have so far 'corrected' 20 million names that exist on social security accounts where the data is 'non-standardised'."

However, there is expected to be some backlash as this process extends further, particularly from the region's Uighur communities, who fear that their traditional culture is being eroded as a result of strict central government regulations.

Hong Kong newspaper the Oriental Daily quoted US-based human rights activist Liu Qing on 25 June as saying that the move was ultimately to "increase control of local authorities over minorities".

Weeks earlier, reports that Xinjiang residents were being asked to provide DNA samples to apply for travel documents raised the same concerns.

Moves to push Mandarin?

Minority groups in western China are not the only ones with fears for the future of their regional languages.

In the past six months, a number of moves to increase the spread of standardised Mandarin have been met with opposition in areas where language is a mark of regional identity.

This has particularly been the case in Hong Kong.

In December 2015, the same month in which Xi Jinping delivered his national unity speech, Hong Kong's government issued new recommendations for students to learn simplified Chinese "to expand students' scope of reading and strengthen exchanges with the mainland and overseas".

Both Cantonese and Mandarin speakers read Chinese, although people in Hong Kong use the traditional Chinese script, while people on mainland China use simplified Chinese.

The government suggestions were vilified in Hong Kong's independent media, and subsequent moves to increase simplified Chinese script in the territory have been met with backlash.

In May, there were protests over Nintendo changing the Hong Kong spelling of the character Pikachu

In February, Hong Kong's media regulator received more than 10,000 complaints after prominent broadcaster Television Broadcasts Limited (TVB) began subtitling one of its Mandarin news programmes with simplified Chinese.

And in May, Japanese game-maker Nintendo's decision to use simplified, instead of traditional Chinese script in its new Pokemon games sparked a petition and protests outside the Japanese consulate.

BBC Monitoring reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

- Published7 June 2016

- Published25 August 2023

- Published25 August 2023