China's forbidden babies still an issue

- Published

Why China's two-child policy still doesn't go far enough for some families.

It is not often that people hiding from the authorities agree to give interviews to the media.

Especially in China.

But after a series of phone calls I meet just such a man, anxious and on edge, but still determined to tell his story.

He is not a criminal, or a dissident, or a government whistle-blower.

In fact his particular misdemeanour would, anywhere else in the world, be considered a cause for pride and joy.

He is hiding, along with the rest of his family, for the simple reason that his wife has just given birth to their third child.

"A third baby is not allowed," he tells me, "so we are renting a home away from our village.

All Chinese couples are now allowed to have two children

"The local government carries out pregnancy examinations every three months. If we weren't in hiding, they would have forced us to have an abortion."

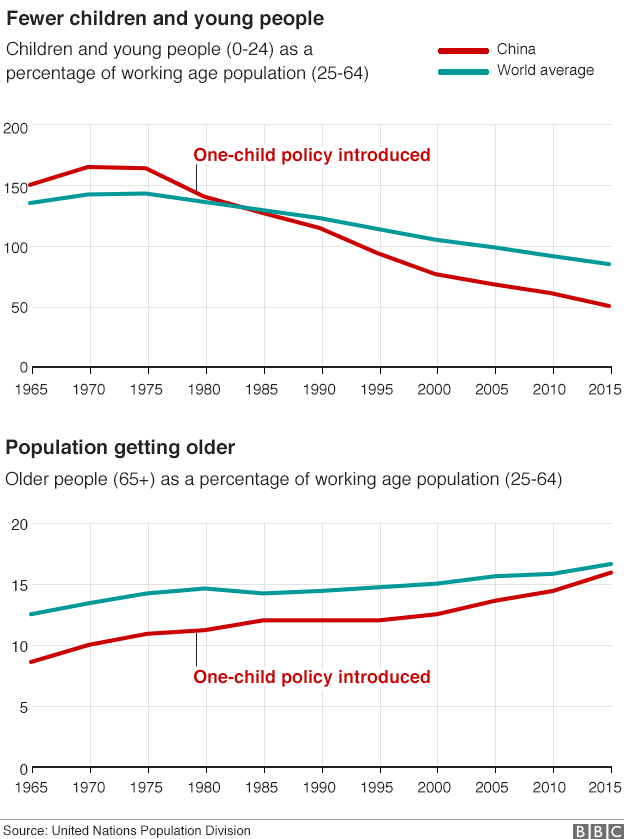

One year ago this week, China announced that what had become perhaps the most widely recognised symbol of Communist Party rule - the one-child policy - was to be scrapped.

It has been replaced instead with a new, universal two-child policy that took effect on 1 January this year.

The old policy - introduced in 1979 to tackle what policymakers saw as the impending crisis of overpopulation - is estimated by the government to have prevented up to 400 million births, in part through the now well-documented use of forced abortions and sterilisations.

So it is little wonder that the mere relaxing of the limit on family size, from one child to two, has done little to assuage the fears of those who fall foul of the new rule.

To mark the first anniversary of the announcement, we set out to investigate what the new policy really means in practice.

And what we have discovered suggests that the brutal machinery of enforcement is still in place along with the Chinese state's insistence on the right of control over women's wombs.

In a grey suburb of a non-descript city in eastern China, I walk, uninvited into one of the notorious family planning centres.

It's a cold, gloomy place the like of which can be found in towns and villages the length and breadth of this vast country.

The floor plan at the entrance adds to the sense of unease.

It shows that this shabby, run-down building contains two ultrasound rooms and three operating theatres.

And when I ask one of the senior officials in charge whether those theatres have ever been used to carry out forced abortions, he pauses.

The age of the one-child family is officially over, but the state is still in charge

"Very few," he finally replies, before going on to insist that none have taken place for "at least 10 years."

Where else in the world would you find a government official admitting that his colleagues have kidnapped, drugged and forcibly operated on women, no matter how long ago?

Where else would the qualifier "very few" be considered an acceptable alternative to an outright denial?

It is an illustration of how the one-child policy has bent and blurred the moral lines and made such state-sponsored violence seem unexceptional.

The official tells me that in his district, under the new two-child policy all women of childbearing age are required to report for two ultrasound examinations every year.

Many families now choose to have just one child

Those found to be pregnant with a third baby "will be advised accordingly", he says.

To get a sense of the wider reality, I ask a female colleague to telephone a number of family planning centres at random.

Pretending to be a mother, pregnant with her third baby but wanting to keep it, she asks the officials what her options are.

According to Chinese law the only legal sanction available to the state for a woman violating the family planning laws is a large fine.

And, as all the officials we speak to on the phone make clear, with the change in policy from one to two children, the fine remains firmly in place.

Levied at up to 10 times annual average income, these fines are often enough in themselves to act as a powerful disincentive to continue with the pregnancy.

But our research shows officials going further, engaging in coercive home visits with the aim of "persuading" women to have abortions.

"If you're reported to us, then we'll find you and we'll persuade you not to give birth to that baby," one said.

"We'll definitely find you and persuade you to do an abortion," said another.

When asked whether our hypothetical mother might actually face physical force, rather than just heavy persuasion, one official said it was still possible "in principle".

Another, in answer to the same question, said: "It's hard to say."

And when asked if a woman could just have the baby and pay the fine yet another official answered: "No. You just can't."

China's one-child policy was scrapped, not out of the recognition that a woman should be free to choose what she does with her own body and her own fertility, but because the Communist Party finally woke up to the economic consequences of the falling birth rate.

The irony is that the two-child policy is too little too late - not enough women are choosing to have even a second baby.

Small families have become the social norm.

That means of course that the pool of people wanting a third child will be even smaller again and some officials we spoke to seemed relatively indifferent, perhaps resigned to their diminishing power in the face of such arithmetic.

"If you want to give birth to your baby, just go ahead," one said, although he was still at pains to stress that the fine would have to be paid.

Our survey is not scientific of course, but it does offer a glimpse into a system that remains rigid and dogmatic.

We found no evidence, no admission, of a forced abortion being carried out since the introduction of the two-child policy, but the threat is clearly still there.

The family in hiding, having escaped that threat, now face a large fine following the birth of their third baby.

"We don't have the money for the fine. We just don't know what to do," the father tells me.

But does he regret it?

"When I look at our new baby, I feel happy," he says.

- Published29 October 2015

- Published29 October 2015

- Published1 January 2016