The Chinese burger designed by Asia's 'best female chef'

- Published

May Chow secretly interned at restaurants to pursue her dream of becoming a chef

The humble steamed bun is taking Hong Kong's culinary scene by storm - and scooping up awards along the way.

May Chow, the owner of restaurant Little Bao, has just been voted Asia's best female chef by a panel of over 300 experts.

The 32-year-old's restaurant serves what she calls Chinese burgers: steamed white buns filled with braised pork belly, fried chicken or fish.

And there are even burgers for dessert, in the form of fried buns sandwiched with ice cream.

Winning the award is no mean feat, considering Asia's competitive food scene, but the restaurant might not have started at all if Ms Chow hadn't sneaked behind her parents' back.

A Chinese burger with braised pork belly

She developed a love of cooking from watching her mother cook in Canada - where a typical meal involved serving more than 20 people in the extended family.

"Growing up I told my parents I wanted to be a chef," Ms Chow tells the BBC.

"But back then, cooking was considered low-class work, and my parents felt it would be a waste of my education."

The buns are assembled with leek and red onions

As a result, Ms Chow studied hotel management at university in the US instead, but says her love for cooking kept calling out to her. By her third year at university, she was ready to take the plunge.

"I didn't tell my parents, but I started interning with restaurants."

That paved her way to becoming a full-time chef at high-end restaurants in Hong Kong.

Her ambition didn't stop at being a chef, either. She says: "The first day I started working at a restaurant, I decided that I wanted to open my own restaurant."

Just a few years later, and after road-testing her dishes at local food markets, Ms Chow opened Little Bao.

A novel take on the humble bao

'Am I really Chinese?'

Bao means bun in Chinese, and Ms Chow says she drew on her own identity, as a Chinese person who had grown up in North America, when designing her signature dish.

"If you define me, my food is exactly me," she says. "Am I really Chinese? Why do I sound so American?"

"That bao is me - Chinese but understands American culture - putting [the two sides] together in an honest way."

She says she is happiest with the authenticity of her buns when her mother and grandmother enjoy them.

Their approval "comes from 30 years of eating bao - you have to stand up to that quality check".

Ms Chow's kitchen is full of mouth-watering smells, including fresh meat being grilled and seafood being fried

Little Bao sells over a hundred buns each day

The buns are cooked in a giant steamer

The dish has also proved a hit with Hong Kong diners and she has just opened a Bangkok branch of Little Bao, as well as a beer bar, Second Draught.

But there were plenty of challenges in the move to becoming a business owner, including the high rents and high build-out costs in Hong Kong.

"It's almost been like taking a real-life business masters degree," she says. "I've grown a lot over the past three years. At first you get emotional, now you just look at things and try to fix problems."

What does she think of being named Asia's best female chef 2017?

It was "stressful", and she jokes that her first reaction, when she learnt of the award, was: "Oh, I don't want it."

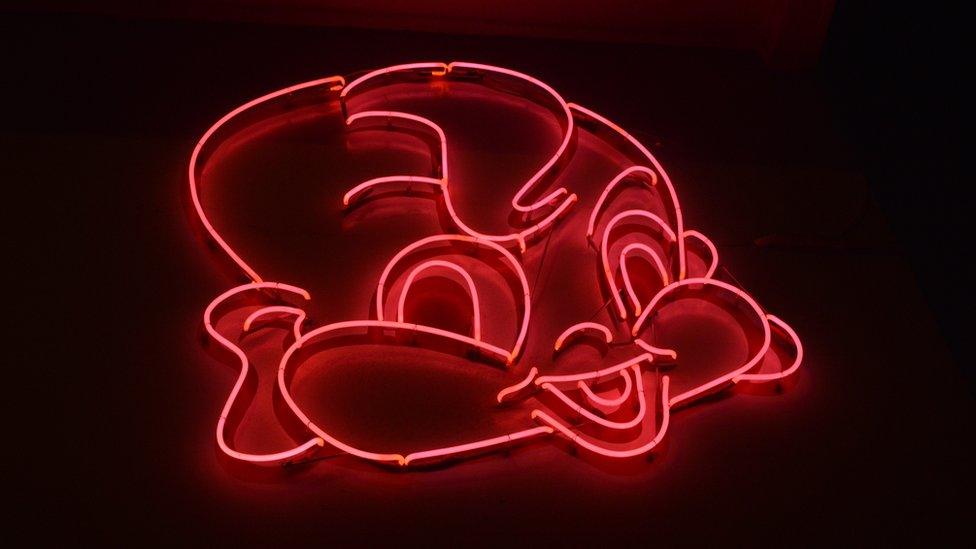

The logo for Little Bao is a smiling baby

There is some pressure that comes with the title, because "there really are not that many female chefs [and] local chefs in that field to be talked about".

She's aware that some will find it strange there is an award specifically for female chefs, but also appreciates how the award has given her a platform to raise awareness about the industry.

She's vocal about what she thinks needs to change to encourage more women, and local Hong Kongers, to join the trade.

Being a chef "is a very labour intensive job. The environment is hot, sticky, typically not a favourable environment."

"Do we really need to work 70 hours a week? Are women allowed to have babies when they're [working] in the kitchen? It's so intense - it's not like a desk job. There are things that need to be improved."

"Shanghai women are fierce and loud"

There isn't always "the freedom to dream" in Hong Kong's competitive education system, she adds.

In the past, vocational jobs were seen as jobs for people who couldn't be doctors or lawyers, so there was "no recognition" for jobs in the food and beverage industry.

Still, she argues that the internet, Michelin guides and growing awareness about fine dining has helped, while local chefs are increasingly learning from restaurants abroad.

On a more personal level, she credits her mother with part of her determination to do well in a male-centric field.

"Stereotypical Shanghai women are fierce and loud," she says with a grin.

Her mother's influence, she adds, "let me be bold. I never grew up thinking I had to limit myself".

- Published10 January 2016

- Published22 November 2015

- Published2 November 2012