'All-out offensive' in Xinjiang risks worsening grievances

- Published

Large rallies by security forces have been held in Xinjiang recently

China is in the midst of what it calls a "people's war on terror" in its far west. What sparked this latest campaign was a knife attack.

After five people were killed on 14 February in Xinjiang, home to China's Muslim Uighur minority, Beijing began an "all out offensive". It flew in thousands of armed troops to hold mass police rallies and deploy columns of armoured vehicles on city streets.

Xinjiang's Communist Party boss Chen Quanguo urged these forces to "bury the corpses of terrorists in the vast sea of a people's war".

Judging from the reaction on Chinese social media, at least some people approve.

"Terrorists will never be stamped out unless we weaken Muslim religious forces," urged one post on China's Twitter-like Weibo.

Then on Monday the so-called Islamic State released a video, which appeared directly to threaten China and which showed Uighur fighters training.

But the ethnic Uighur population of Xinjiang has no discernible voice. In the midst of an "all-out offensive" it is dangerous for them to speak up, unless to echo the government's message.

One contact in Kashgar told the BBC that the situation is "hypersensitive", with all business in the city closed down by night. He said members of his family are summoned to weekly meetings to demonstrate political allegiance.

"We are reliving the Cultural Revolution", he said.

Uighurs and Xinjiang

Uighurs are ethnically Turkic Muslims

They make up about 45% of Xinjiang's population; 40% are Han Chinese

China re-established control in 1949 after crushing the short-lived state of East Turkestan

Since then, there has been large-scale immigration of Han Chinese

Uighurs fear that their traditional culture will be eroded

So what lies behind China's biggest show of force in Xinjiang in nearly a decade?

The incident in Pishan on 14 February is the only deadly attack to be reported this year. Details are still scarce but there is no suggestion of the kind of outside involvement or large scale co-ordination which might explain such an enormous response.

Instead, unofficial reports suggest the trigger for the attack may have been something far more personal: the police punishment of a Uighur family who held a Muslim prayer meeting at home.

This is surely not the kind of scenario which requires the deployment of thousands of paramilitary reinforcements.

But the state controlled Xinjiang Daily newspaper has urged security forces to prepare "for a battle between good and evil, lightness and dark" and the region's Communist Party boss warned of "grim conditions" in the fight against terrorism.

As well as the firm hand of Beijing, Uighurs are involved in the running of their semi-autonomous region

So are conditions really grim?

Notwithstanding the video threat, outside Xinjiang, there has been no significant terrorist attack in China since 2014 and reported attacks in the region have been sporadic and small-scale.

By contrast, France has seen numerous terror attacks in recent years, including several major atrocities. But the French government did not declare a frontline, fly in thousands of troops or mount mass armed rallies on city streets.

It's hard to escape the conclusion that China is wielding a hammer to crack a nut. But Xinjiang's security forces are already well armed with every form of "nutcracker", including highly trained manpower, rapid response units, mobile police stations, surveillance cameras, helicopters, drones, satellite tracking of vehicles, biometrics and grid style management of every community right down to the individual household.

Police control and public surveillance is on the rise across China

So what explains the force?

It's possible that the current security situation in Xinjiang is worse than appears and that there are many attacks going unreported.

Or that China has a very different risk calculus from other countries and feels a hammer is the appropriate response to every nut.

A third possibility is that warning of "grim conditions" in counter-terrorism serves an unrelated purpose and the nut must be redefined as an existential threat to justify the hammer.

My feeling is that all three explanations play a part.

The first is the least significant.

It's hard to verify occasional unofficial reports of small scale attacks in remote parts of Xinjiang because it's extremely difficult and dangerous for local Uighurs to contact foreign reporters. But it's unlikely that the authorities could cover up a major atrocity even if they wished to.

The risk calculus is a much bigger factor. It's a sweeping generalisation unsupported by hard evidence, but in my experience Chinese citizens are risk averse.

They have a higher expectation than, for example, British citizens, that their government must keep them safe.

China's growing authoritarianism means there is no vocal constituency arguing that civil liberties are worth a certain price in national security. Besides which, low trust in official news sources makes Chinese society susceptible to rumour and panic.

So China's leaders have to be risk averse when dealing with a high density population, which is only grudgingly loyal in the first place and unlikely to be resilient to terror or tolerant of failure to prevent it.

In Xinjiang, recent attacks may be small, but Beijing needs to show its public that it is doing something about them, even if that something is ineffectual or worse, counter-productive.

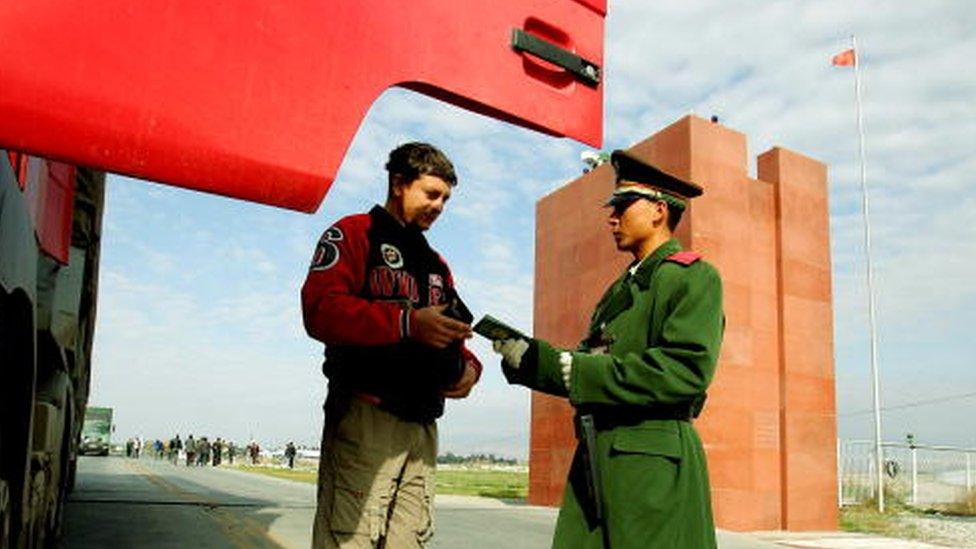

The region's security forces are already well trained and armed

Turning to the third possible motive for an "all-out offensive" against scattered enemies armed only with knives, China has powerful vested interests whose objectives are advanced by talking up the security threat.

The politicians involved want to strengthen their hand before a crucial Communist Party Congress in the autumn, the security services want to expand their bureaucratic empire, and the businesses producing surveillance equipment and software have money to make.

Ethnic riots in 2009 left nearly 200 dead and led to mass arrests, against which these women protested

Despite China's best efforts to cut off the routes of escape via Central and South East Asia, more than 100 Uighur fighters have made their way to Iraq and Syria. And now, IS is using footage from Xinjiang in its propaganda videos.

It's impossible to judge how far this would have happened without policies of religious and cultural repression in Xinjiang.

Banning beards and head scarves in public places, forcing Muslims to break their rules on fasting, demolishing mosques, micromanaging religious education, exacting outward shows of ideological loyalty serves to alienate Uighurs in Xinjiang.

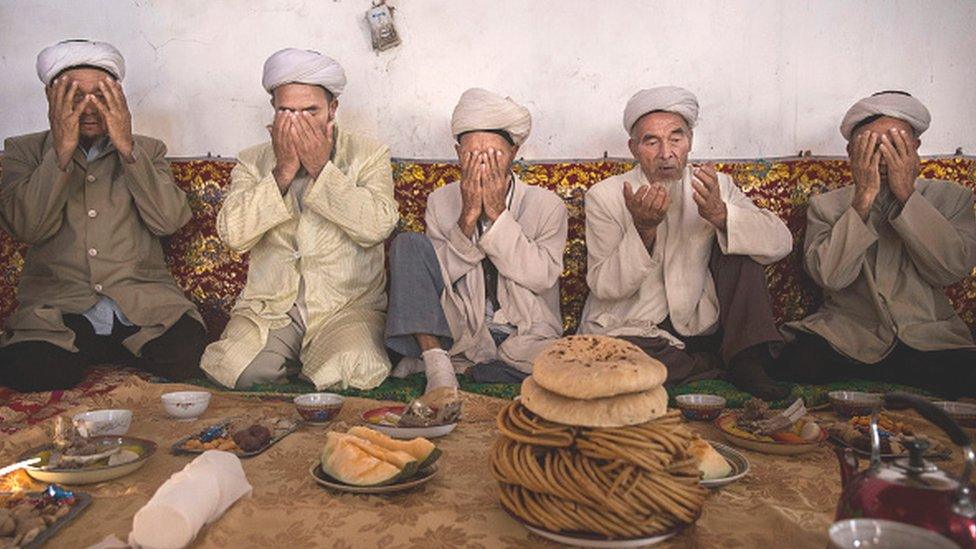

Some Uighurs feel their distinct culture is under threat

In many countries terror triggers the impulse to repress and punish the community which appears to harbour the "terrorist". But other societies debate the dangers of alienation and the risk that those criminalised may become even more vulnerable to exploitation by extremists.

In 2014, making the case for an honest appraisal of the dangers of repression earned the Uighur academic Ilham Tohti a life sentence in prison.

The risk of demonising such mild dissent is to leave China's Uighurs only the voice of the separatist, the "terrorist" or the religious fundamentalist.

Despite relatively moderate activism, Uighur academic Ilham Tohti was jailed for life

At present, the cost of this silence is experienced only by Uighurs and by Han Chinese who live and work in Xinjiang. But this may change.

Already the technologies of an Orwellian police state are advancing across China. Security services have no inhibitions about accessing social media accounts and private financial records to build an increasingly complete picture of the lives of persons of interest.

A vaguely worded new anti-terror law and accompanying narrative of foreign threats justify every constriction of civil liberties and detention of human rights lawyers, labour activists, religious believers and feminists.

Most of the Uighur ethnic minority, which makes up about 45% of Xinjiang's population, practise the Muslim faith

Occasionally the Chinese public pushes back with complaints on social media about aggressive policing or miscarriages of justice.

And China does have traditions of soft power as well as hard - strains of Confucian paternalism in which a benign emperor rules through wisdom and natural authority, not through fear.

But in 2017, these strains are absent in Xinjiang. There's no significant pushback to the Communist Party message that the security of the state trumps the liberty of the citizen.

So China will go on failing to win the battle for hearts and minds in Xinjiang, and failing to convince the outside world that its offensive there is a clear-cut battle between good and evil.

- Published28 February 2017

- Published21 February 2017

- Published24 November 2016

- Published25 August 2023

- Published26 September 2014

- Published24 May 2022

- Published24 February 2017

- Published27 January 2017