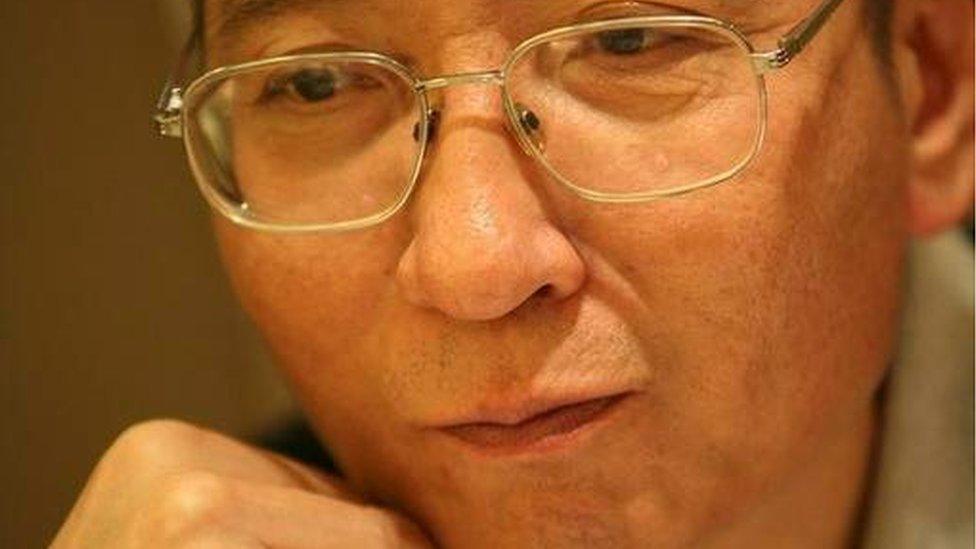

Liu Xiaobo: The man China couldn't erase

- Published

Activist Liu Xiaobo has died after spending eight years in prison

"There is nothing criminal in anything I have done but I have no complaints."

So stated Liu Xiaobo in court in 2009, and in the eight long prison years between then and now, he refused to recant his commitment to democracy. No wonder China's leaders are as afraid of him in death as they were in life.

The Chinese Communist Party was once a party of conviction, with martyrs prepared to die for their cause, but it's had nearly 70 years in power to become an ossified and cynical establishment. It imprisons those who demand their constitutional rights, bans all mention of them at home and uses its economic might abroad to exact silence from foreign governments. Under President Xi, China has pursued this repression with great vigour and success. Liu Xiaobo is a rare defeat.

Beijing's problem began in 2010 when he won a Nobel Peace Prize. That immediately catapulted Liu Xiaobo into an international A-list of those imprisoned for their beliefs, alongside Nelson Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi and Carl von Ossietzky.

The last in that list may be unfamiliar to some, but to Beijing he's a particularly uncomfortable parallel. Carl von Ossietzky was a German pacifist who won the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize while incarcerated in a concentration camp. Hitler would not allow a member of the laureate's family to collect the award on his behalf.

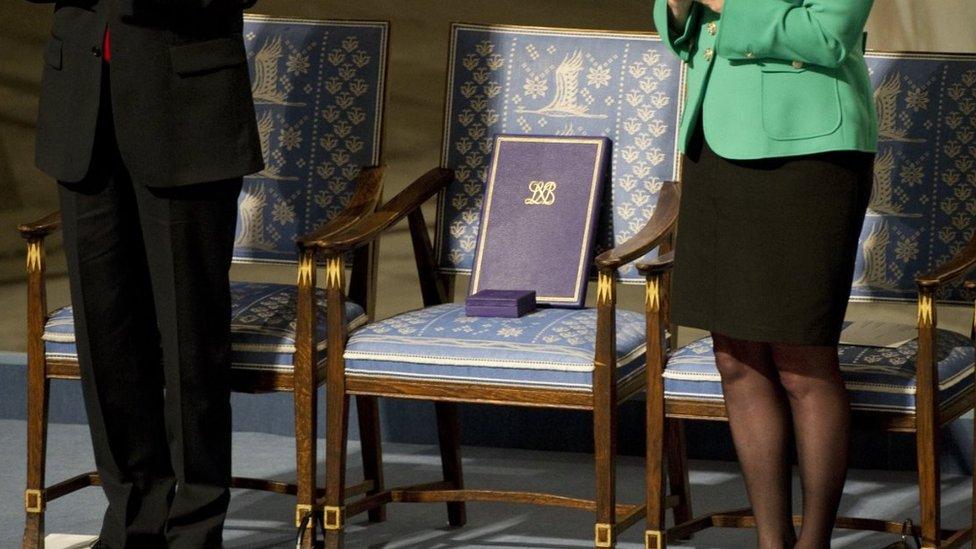

Liu Xiaobo was also serving a prison sentence for subversion when he won the peace prize. Beijing would not let his wife collect the award and instead placed her under house arrest. Liu Xiaobo was represented at the 2010 award ceremony in Oslo by an empty chair and the comparisons began between 21st Century China and 1930s Germany.

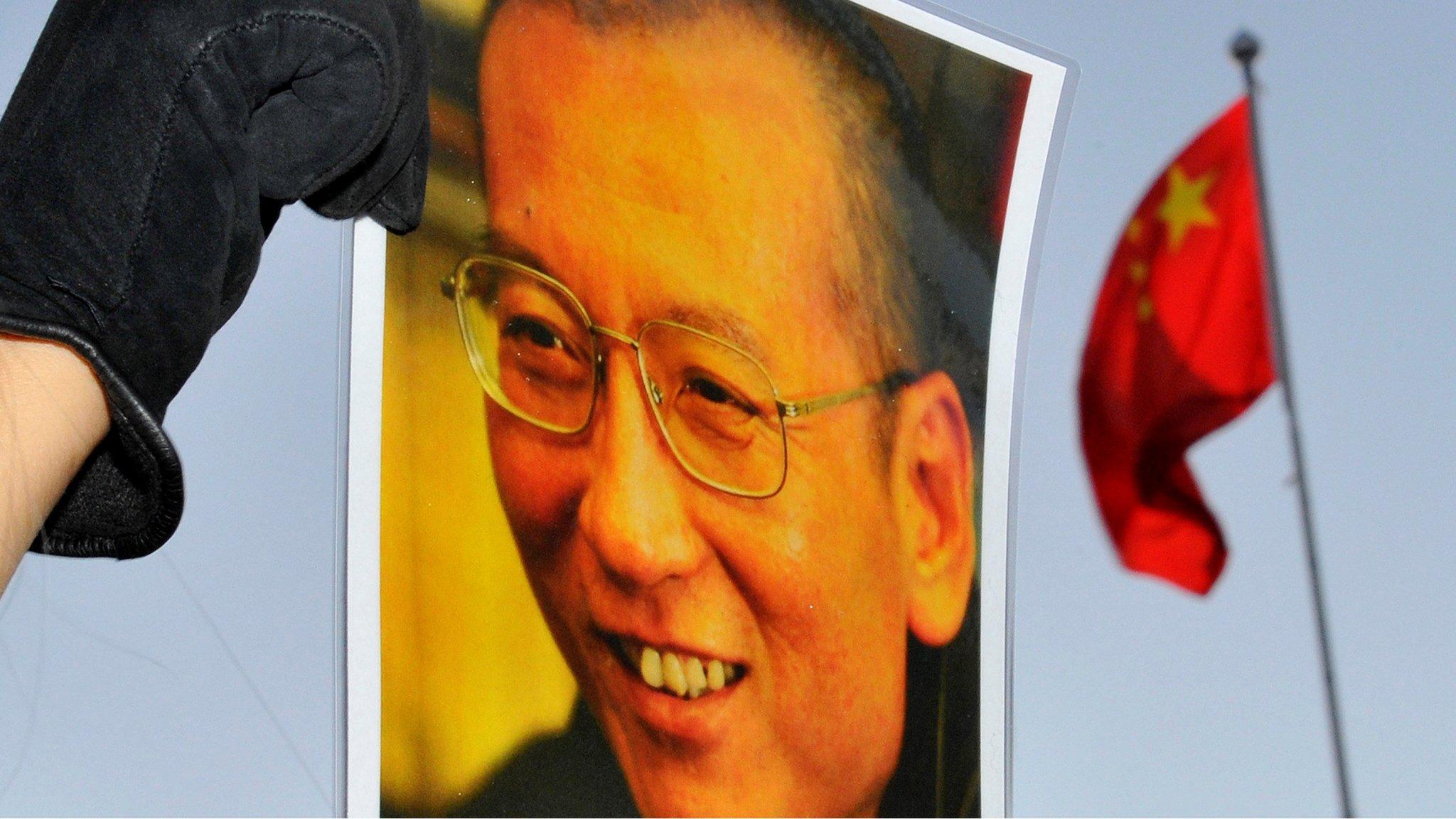

While in jail, Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. An empty chair was left for him at the ceremony

Strict censorship is another shared feature of both cases. Mention of Carl von Ossietzky's 1935 Nobel peace prize was banned in Nazi Germany and the same is true of Liu Xiaobo's award in China today. For a time China even banned the search term "empty chair". So he has been an embarrassment to China internationally, but at home few Chinese are aware of him. Even as foreign doctors contradicted the Chinese hospital on his fitness to travel, and Hong Kong saw vigils demanding his release, blanket censorship in mainland China kept the public largely ignorant of the dying Nobel laureate in their midst.

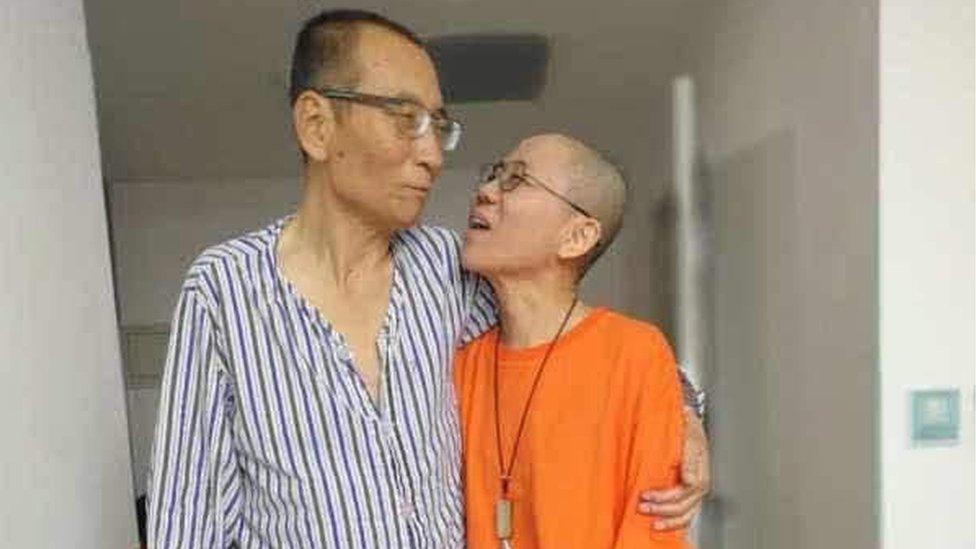

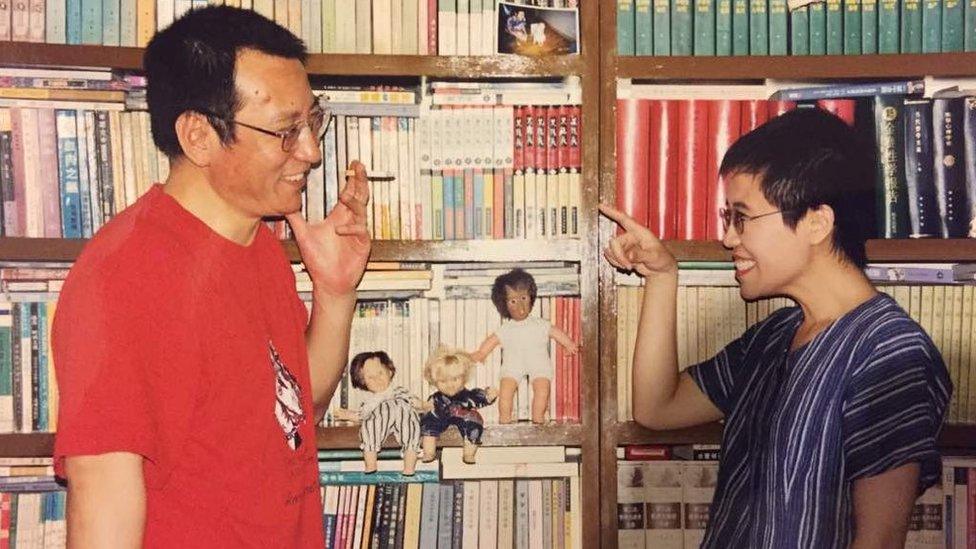

Selective amnesia is state policy in China and from Liu Xiaobo's imprisonment until his death, the government worked hard to erase his memory. To make it hard for family and friends to visit, he was jailed nearly 400 miles from home. His wife Liu Xia was shrouded in surveillance so suffocating that she gradually fell victim to mental and physical ill health. Beijing punished the Norwegian government to the point where Oslo now shrinks from comment on Chinese human rights or Liu Xiaobo's Nobel prize.

Liu Xiaobo (left) is seen here with his wife Liu Xia (right) in this undated photo

But in death as in life, Liu Xiaobo has refused to be erased. The video footage of the dying man which China released outside the country was clearly intended to prove to the world that everything was done to give him a comfortable death. The unintended consequence is to make him a martyr for China's downtrodden democracy movement and to deliver a new parallel with the Nobel Peace Prize of 1930s Germany.

Liu Xiaobo was granted medical parole only in the terminal stage of his illness, and even in hospital he was under close guard with many friends denied access to his bedside. Nearly 80 years ago, Carl von Ossietzky also died in hospital under prison guard after medical treatment came too late to save him.

Comparisons with the human rights record and propaganda efforts of Nazi Germany are particularly dismaying for Beijing after a period in which it feels it has successfully legitimised its one-party state on the world stage. At the G20 summit in Hamburg earlier this month, no world leader publicly challenged President Xi over Liu Xiaobo's treatment. With China increasingly powerful abroad and punitive at home, there are few voices raised on behalf of its political dissidents.

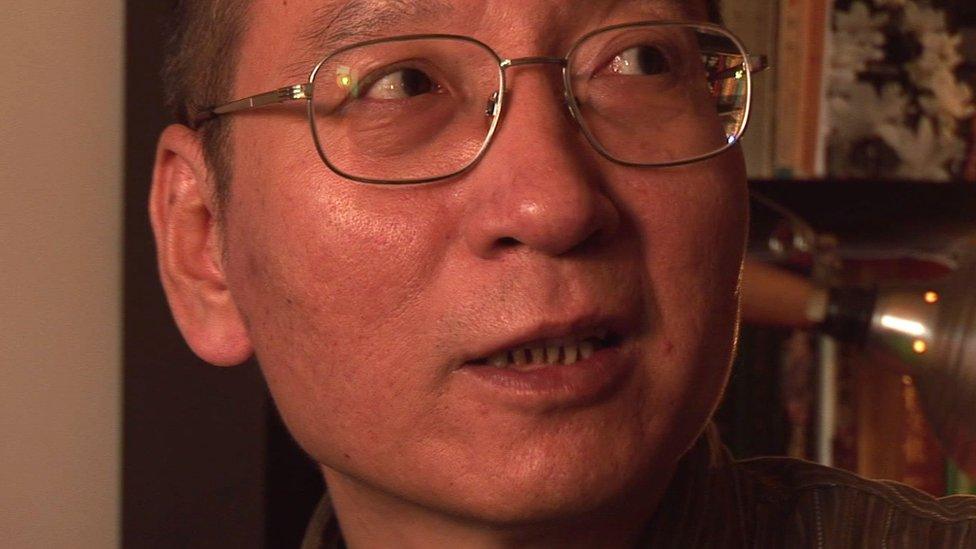

Liu Xiaobo was not always a dissident. An outspoken academic with a promising career and a passport to travel, until 1989 he'd led a charmed life. The Tiananmen Square democracy movement that year was the fork in his path. After the massacre on June 4th, the costs of defying the Party were tragically clear to all.

Most of his contemporaries, and of the generations which followed, judged those costs too high. They chose life, liberty and a stake in the system.

Liu Xiaobo was one of the few who took the other fork. He stayed true to the ideals of 1989 for the rest of his life, renouncing first his opportunities to leave China, and then, repeatedly, his liberty. Even in recent years, his lawyers said he had turned down the offer of freedom in exchange for a confession of guilt.

'If you want to enter hell, don't complain of the dark....'

Liu Xiaobo once wrote. And in the statement from his trial which was read at his Nobel award ceremony alongside his empty chair, Liu Xiaobo said he felt no ill will towards his jailers and hoped to transcend his personal experience.

No wonder such a man seemed dangerous to Beijing. For a jealous ruling party, an outsider with conviction is an affront, and those who cannot be bought or intimidated are mortal enemies.

But for Liu Xiaobo the struggle is over. The image of his empty deathbed will now haunt China like the image of his empty chair. And while Beijing continues to intimidate, persecute and punish those who follow his lead, it will not erase the memory of its Nobel prize winner any more than Nazi Germany erased its shame 81 years ago.

- Published13 July 2017

- Published9 July 2017

- Published9 July 2017

- Published11 July 2017