Five charts about the fortunes of the Chinese family

- Published

In the five years since President Xi Jinping moved to the helm, China has become richer and more powerful. But what has this growth meant for the fate and fortunes of the ordinary Chinese family?

As China's most powerful decision-makers meet to set the course of the nation for the next five years and a new generation of leaders emerges, we look at data from Chinese authorities and major surveys, to get some clues about how China's family life and society is changing.

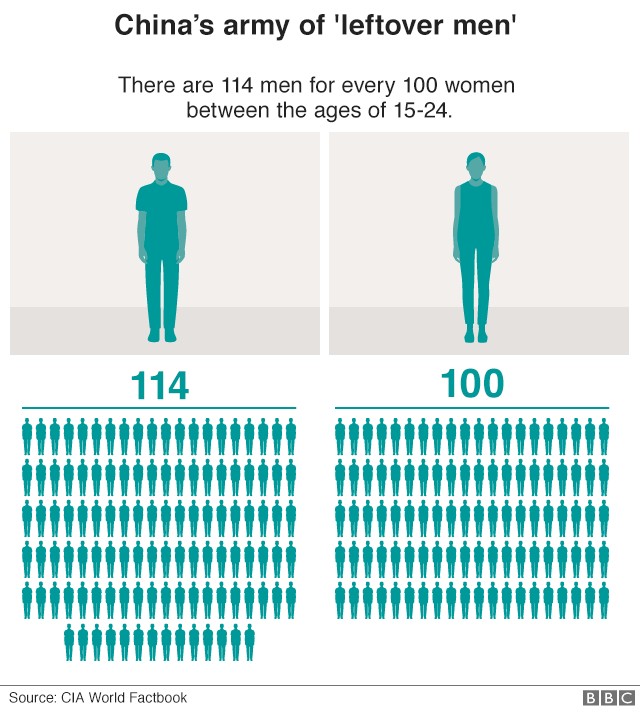

In 2015, the government threw out its notorious one child policy which had been intended to keep population figures low but had led to a crippling gender imbalance.

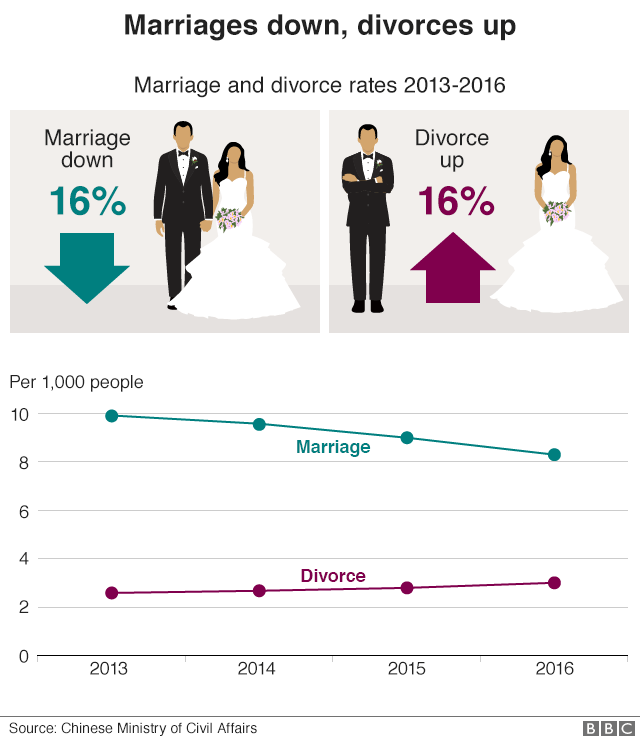

So while now the door is open for more kids and bigger families, a look at marriage and divorce rates increasingly shows the same trend as the rest of the developed world: Marriage rates are falling while more and more people end up divorced.

Yet this first impression might be misleading.

"China has always had and is still having a much lower divorce rate than US and western European countries," Xuan Li, assistant professor of psychology at New York University Shanghai, explains.

"A much higher percentage of mainland Chinese people marry eventually, in comparison to those in neighbouring areas and countries. So the idea that the Chinese families (and ergo, the society and nation) are falling apart is statistically ungrounded."

China might have overturned its one-child policy in 2015 yet its legacy will continue to be a problem for years to come. There is even a term for unmarried men over 30: Shengnan, meaning "leftover men".

In 2015, a Chinese businessman in his 40s reportedly sued a Shanghai-based introductions agency for failing to find him a wife, having paid the company 7m yuan ($1m, £780,000) to conduct an extensive search.

"China's one-child policy advanced and amplified a demographic transition," explains Louis Kuijs of Oxford Economics. "Falling birth rates and an aging population have been exerting downward pressure on the labour force and thus on economic growth."

"Although the one-child policy was changed in January 2016 into a two-child policy, higher birth rates now will only show up in the labour force in around two decades," he estimates.

But higher standards of living are slowly affecting traditional gender perceptions and that in turn will have a positive effect on the gender imbalance.

"The gender imbalance is already changing," Mu Zheng of the Centre for Family and Population Research at National University of Singapore told the BBC.

"That's because of the relaxed fertility policy, changing attitudes, women's advanced profiles in both education and work, and with a more established social security system,"

But for now, the current gender imbalance does make it hard for men to find wives.

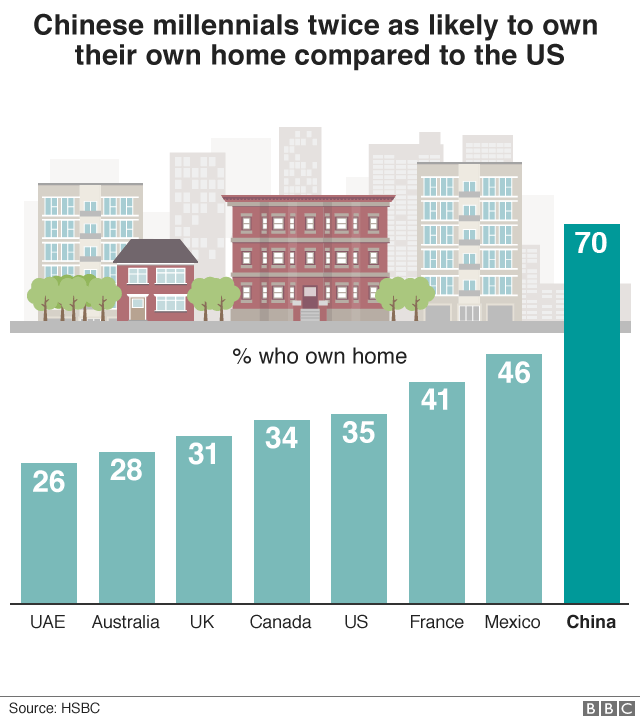

Amid the constant talk about China's housing bubble about to burst, here's a detail that stands out: Among millennials, China has a towering percentage of homeowners, a different league it seems from European countries or the US.

While the above data from HSBC, external largely covers urban China, it still illustrates a crucial point: parents are trying whatever they can to equip their sons with some added extras to woo women into wedlock.

"It is the custom that husbands will provide a home," Dr Jieyu Liu, deputy director of the SOAS China Institute, told the BBC in April when HSBC released the data.

"Many love stories fail to turn to marriage if the men fail to provide a marital house."

So once charm, luck or a property have helped China's singles get hitched - what is life like for families?

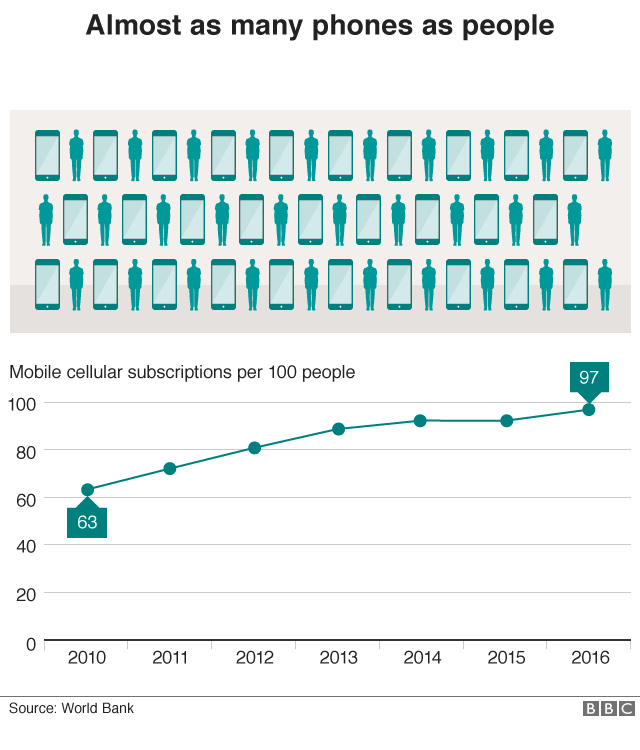

China's average income has seen a steady rise, both in rural and in urban areas. While the relative expenses on food have dropped significantly over the past decade, the money spent on things like health, clothes or transport has gone up. The same goes for communications. The surge in mobile phones illustrates that point.

Smartphones are not just another communications expense - the WeChat app for instance is so woven into everyday routines that life without a phone is virtually unthinkable.

"WeChat is designed as an app that is like a toolkit for life, sort of a digital Swiss Army knife," Beijing-based tech analyst Duncan Clark of ABI Research explains.

He says consumers have been embracing the convenience of it covering everything from paying utility bills, cashless payments in shops, taxis and bike rentals, money transfers and of course - communication.

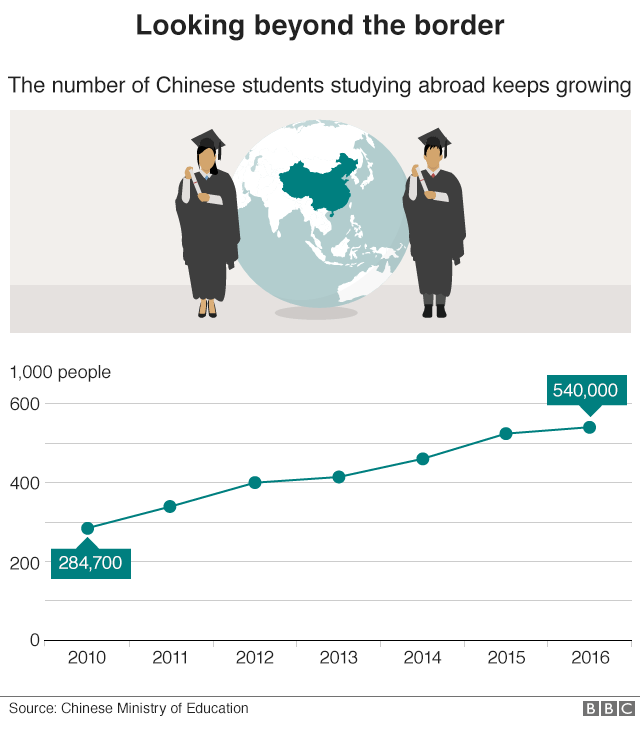

Higher incomes translate into more money spent on children's education and recent years have shown a steady rise in parents sending their children overseas to study. What's more, they are coming back.

"A large proportion of these students are returning to China, with 433,000 having returned in 2016," explains Rajiv Biswas, APAC chief economist at analytics firm IHS Markit.

This rapidly growing pool of Chinese graduates with international degrees and experience of living abroad will make the next generation of Chinese business and government leaders "very international in their thinking and understanding of other cultures, which will be increasingly important as China assumes the mantle of the world's largest economy in about a decade".

And while a degree from a European or US university is likely to boost your chances on the job market - it might also drive up your chances of bagging the right partner.

Reporting by Andreas Illmer.

Graphics produced by Wesley Stephenson, Mark Bryson and Sumi Senthinathan.

- Published8 October 2017

- Published11 October 2017

- Published7 October 2017

- Published23 January 2017

- Published6 April 2017