Tiangong-1: China space lab to plunge to Earth on Monday

- Published

Artwork: Most of Tiangong-1 will go up in flames on re-entry

Debris from a defunct Chinese space station is seen crashing to Earth on Monday, scientists monitoring it say.

China's space agency said the station will re-enter the atmosphere in the next 24 hours - in line with European Space Agency (ESA) predictions.

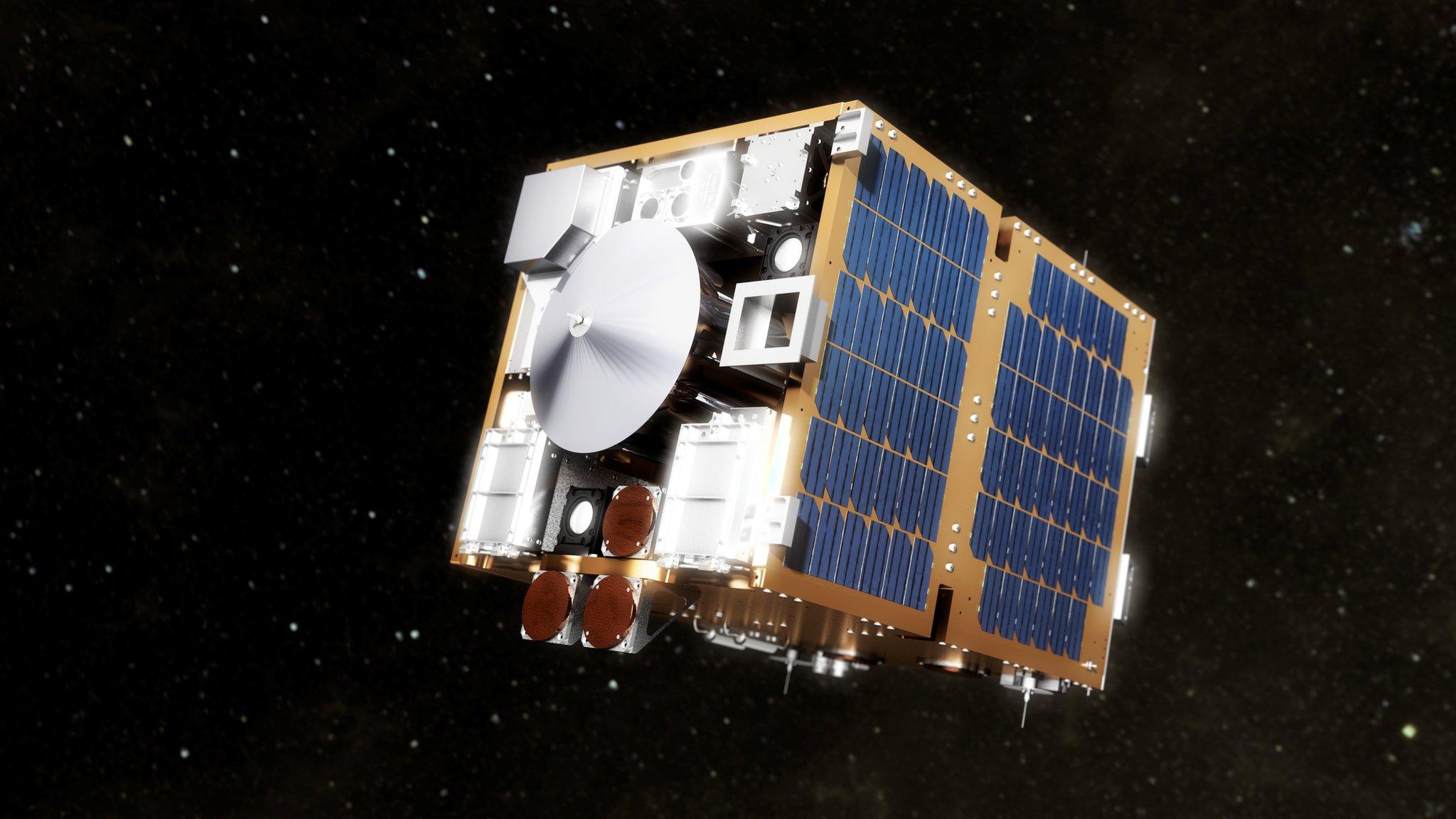

The Tiangong-1 was part of China's ambitious space programme, and the prototype for a manned station in 2022.

It entered orbit in 2011 and five years later ended its mission, after which it was expected to fall back to Earth.

The latest projection from the Esa points to re-entry at 07:25 Beijing time (00:25 GMT) on 2 April, although the window is still "highly variable" - stretching from Sunday afternoon to Monday morning.

Most of the station is likely to burn up in the atmosphere but some debris could survive to hit the surface of the Earth.

The China Manned Space Engineering Office said on social media that falling spacecraft do "not crash into the Earth fiercely like in sci-fi movies, but turn into a splendid (meteor shower)".

Where will it crash?

China confirmed in 2016 that it had lost contact with Tiangong-1 and could no longer control its behaviour, so we don't really know where it will end up.

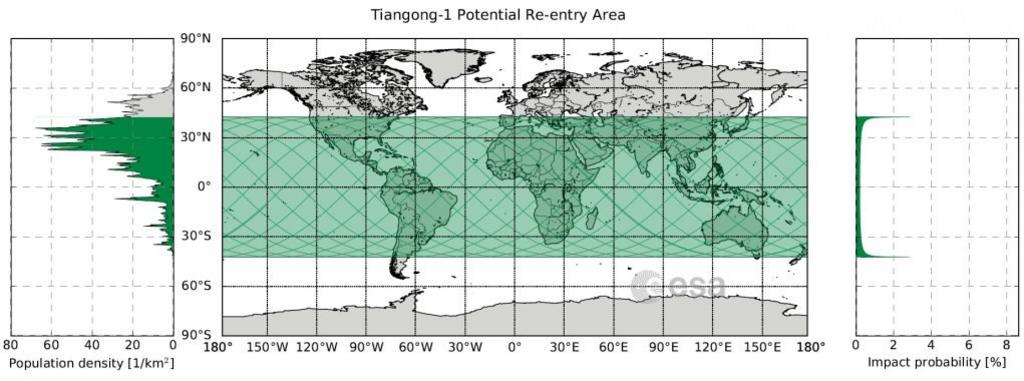

The European Space Agency (ESA) said re-entry "will take place anywhere between 43ºN and 43ºS", external, which covers a vast stretch north and south of the equator.

Esa says this means the station could fall anywhere from New Zealand to the midwestern US.

How will it crash?

The station is gradually coming close to Earth.

Its rate of descent "will continually get faster as the atmosphere that the station is ploughing through gets thicker," Dr Elias Aboutanios, deputy director of the Australian Centre for Space Engineering Research, told the BBC.

China launched Tiangong-1 in 2011

"The station will eventually start to heat up as it gets close to 100km [from Earth]," he says.

This will lead to most of the station burning up and "it is difficult to know exactly what will survive since the makeup of the station has not been disclosed by China".

The station could reach speeds of up to 26,000km/h (16,156mph).

Should I be worried?

No. Most of the 8.5-tonne station will disintegrate as it passes through the atmosphere.

Some very dense parts such as the fuel tanks or rocket engines might not burn up completely. However, even if parts do survive to the Earth's surface, the chances of them hitting a person are incredibly slim.

"Our experience is that for such large objects typically between 20% and 40% of the original mass will survive re-entry and then could be found on the ground, theoretically," the head of Esa's space debris office, Holger Krag, told reporters at a recent briefing.

"However, to be injured by one of these fragments is extremely unlikely. My estimate is that the probability of being injured by one of these fragments is similar to the probability of being hit by lightning twice in the same year."

Does all space debris fall to Earth?

While debris regularly comes back down, most of it "burns up or ends up in the middle of the ocean and away from people," says Mr Aboutanios.

Usually there is still communication with the craft or satellite. That means ground control can still influence its course and steer it to a desired crash site.

The debris is steered to crash near what's called the oceanic pole of inaccessibility - the furthest place from land. It's a spot in the South Pacific, between Australia, New Zealand and South America.

Over an area of approximately 1,500 sq km (580 sq miles) this region is a graveyard of spacecraft and satellites, where the remains of around 260 are thought to be scattered on the ocean floor.

What is Tiangong-1?

China was a late starter when it comes to space exploration.

China's first man in space in 2003 became national hero

In 2001, China launched space vessels carrying test animals and in 2003 sent its first astronaut into orbit, making it the third country to do so, after the Soviet Union and the US.

The programme for a space station kicked off in earnest with the 2011 launch of Tiangong-1, or "Heavenly Palace".

The small prototype station was able to host astronauts but only for short periods of several days. China's first female astronaut Liu Yang visited in 2012.

It ended its service in March 2016, two years later than scheduled.

Currently, Tiangong-2 is in operation and by 2022, Beijing plans to have number 3 in orbit as a fully operational manned outpost in space.

- Published21 October 2017

- Published8 April 2017

- Published28 November 2017

- Published15 June 2017