'The week that changed the world': How China prepared for Nixon

- Published

The meeting between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un will be one of the most important encounters between former enemies, with echoes of President Nixon's 1972 visit to China.

China at the time was isolated from the outside world amidst the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. And just as Kim Jong-un has been telling the North Korean people that they need to co-exist peacefully with the US, the Chinese government had to convince its people that it was necessary to welcome the Americans.

The BBC's Yuwen Wu was a young student in 1972 and reflects on how China prepared for what Nixon described as "the week that changed the world".

On 15 July 1971 at 19:00 local time, US President Richard Nixon walked into an NBC television studio in California and announced to the world that he had accepted an invitation from Premier Zhou Enlai to visit China, "to seek the normalisation of relations between the two countries".

At exactly the same time, 10:00 on 16 July in Beijing, China's national broadcaster made the same announcement, which made it clear that it was President Nixon who had first expressed his wish to visit the People's Republic of China.

This carefully choreographed broadcast was emblematic of both countries' painstaking preparation for Nixon's icebreaking trip to Beijing that sent shock waves across the world.

Mao's strategic calculation

The decision to invite the Americans came as relations between China and the Soviet Union were worsening, and the realisation for China that it faced a greater threat from its ally to the north than from its "enemy" across the Pacific Ocean. Reaching out to the Americans to leverage the existing tensions to China's advantage took on urgent strategic importance.

That realisation led to a series of events that would culminate in the establishment of formal diplomatic relations in 1979.

First, Mao Zedong spoke to the American journalist Edgar Snow in 1970 about his willingness to improve relations with Washington. In April 1971, China invited the US table tennis team for a visit.

A few months later, Henry Kissinger - Nixon's security adviser - made a secret visit to Beijing, during which China extended its invitation to President Nixon.

'We immediately recognised the significance of this' - the moment when Nixon met Mao

As is the case with China then and now, once the objectives were set, various mechanisms of state power began working to ensure the success of the trip, including the propaganda machine, the security apparatus and efforts to mobilise the masses.

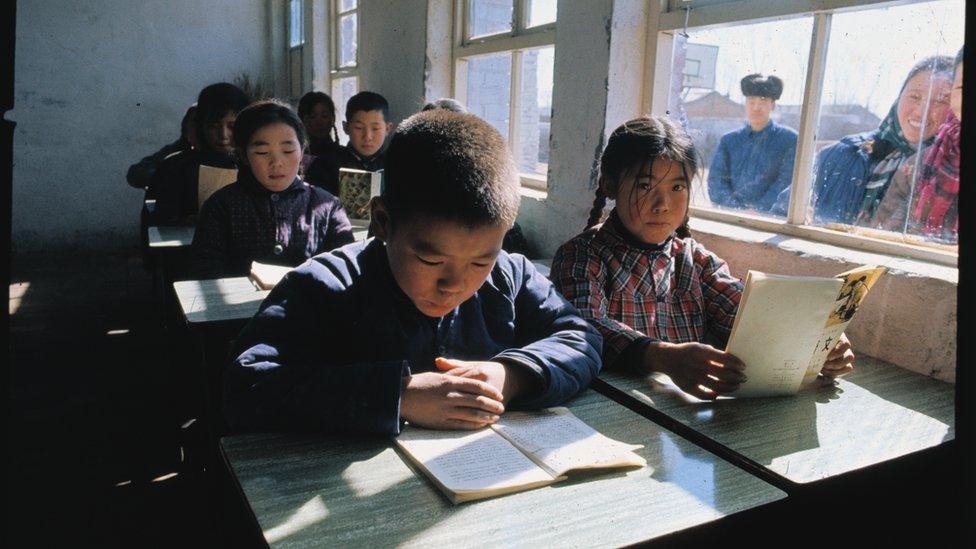

I was 15 at the time, attending secondary school in Beijing. I don't remember much about the actual visit, and all the friends I have talked with also only have very faint memories.

But we all remember one thing, which is the general stance towards the American visitors that the government had stipulated: "Neither humble nor arrogant, neither cold nor hot."

It was years later that I learned about many interesting and sometimes hilarious examples of this general principle in action.

Beijing schoolchildren were told they could just run away if asked difficult questions by the American visitors

No insults 'to their face'

Yang Zhengquan, former chief of the Central Broadcasting Station, recalls the general guidance for media reporting being that there had been "no change regarding China's attitude to the USA".

Meaning, "we are still against them, but President Nixon is our guest, so we can't shout 'Down with Nixon' and 'Down with US Imperialists' to their face".

As a result, the "US imperialists" moniker would be changed to "USA" in radio and TV bulletins for the duration of Nixon's visit. Some anti-American content could still be produced but it should not be excessive.

China also understood how the visit was being seen in the US, and how Nixon would want to use live broadcasting to keep the American people informed of the progress in Beijing. US technicians initially wanted to set up a satellite station, but Beijing wouldn't allow it.

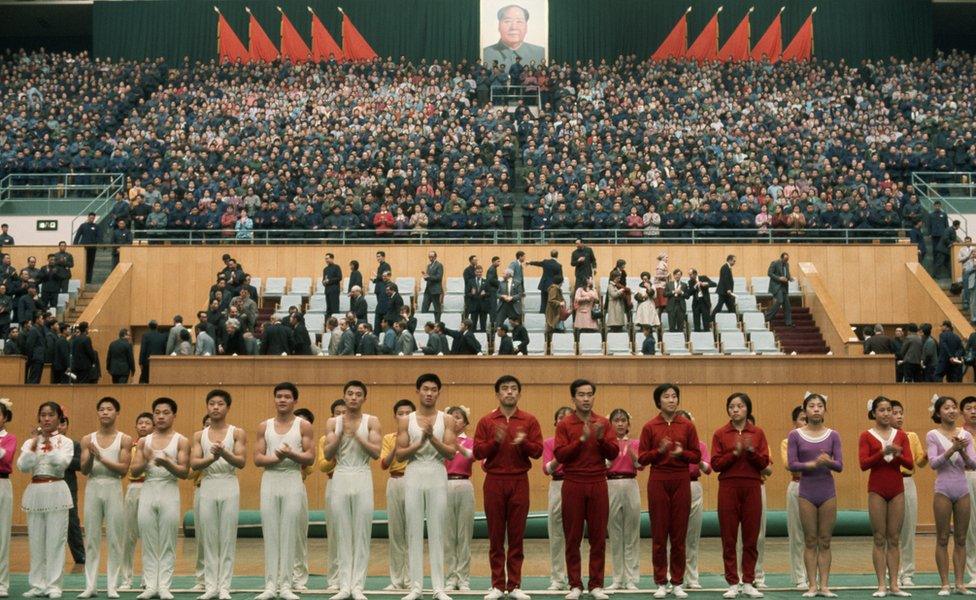

Chinese gymnasts performed for the US delegation

To break the deadlock, with Premier Zhou's permission, the Chinese side bought the US satellite equipment, and then rented it back to the US team so they could broadcast their evening news live from China.

Security, security and more security

Security for the visit was of huge concern. The hosts had to ensure the visit would go smoothly without any unexpected incidents; they also wanted to prevent inquisitive Americans from finding out too much about this mysterious country.

As the visit loomed, a big security operation was staged in the capital, with many people classified as "class enemies" put under house arrest or surveillance.

There were also reports of school and work hours being extended in Beijing to make sure not too many people would be outside before eight in the evening.

Back at my school, my teacher recalls that all the staff were told to look after or control their own classes so there would be no trouble in the streets. She also remembers that a student from another class was arrested simply for carrying a knife.

Some students were also told how to deal with foreign journalists who might ask tricky questions such as, "Where is Marshall Lin Biao?"

The former Communist Party leader and Mao's chosen successor had fled China and died in a plane crash in Mongolia. Students were told this was "still top secret and not to be revealed to foreigners".

Other queries they prepared for included: "Do you have enough to eat and wear?" and "Do you like America?".

Students could pretend they didn't understand the questions, or just run away.

Fake tourists on the wall

In order to create a friendly and orderly atmosphere, neighbourhoods were given a thorough clean-up, with unsuitable slogans and quotations removed and new ones more fit for the occasion put up to replace them.

Truckloads of supplies were ferried to shops to fill the shelves, with a wider variety of goods on offer than usual.

Much of the interaction between the Nixon party and "normal" Chinese people also appeared to be staged by Beijing.

American journalist Max Frankel from New York Times was part of the press corps and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for his reports about Nixon's February 1972 visit.

He observed on Nixon's trip to the Great Wall on 24 February, external that "strategically placed atop of the Great Wall in his path was a group of 'typical' tourists who could just happen to be on hand for a cordial greeting before the cameras and to allow a smartly dressed young woman to extend a special hand of welcome".

Nixon called the Great Wall: "A symbol of what China in the past has been and of what China in the future can become."

It turns out that these "tourists" were especially chosen to perform this political task.

In 2008, a man writing for the Phoenix News website said that he was working in a small factory when he was asked to pick 10 politically reliable people to take part in an event. They were asked to dress well - no work clothing allowed. They would pretend to be tourists on the Great Wall, and they would keep a fair distance from the American dignitaries, while pretending not to understand if they asked any questions.

A breakthrough

It snowed heavily the evening before the Great Wall visit, and thousands of Beijing residents and army personnel worked through the night to clear the streets so the Americans could drive. This deed was greatly appreciated by the visitors, but the wall itself made a bigger impression on President Nixon, who called it a "symbol of what China in the past has been and of what China in the future can become".

He told the journalists and Chinese guests: "As we look at this wall, we do not want walls of any kind between peoples."

Relations between the US and China have gone through many ups and downs since 1972, but it's fair to say the historic Nixon visit made it possible for the relationship to be built and tested in the first place.

Now all eyes will be on the Trump-Kim summit, with the hope that it will mark the beginning of the end of six decades of hostility and the start of peace and stability on the Korean peninsula.

- Published22 March 2017

- Published23 January 2014

- Published7 April 2018

- Published6 June 2018