Obituary: Shan Tianfang, China's beloved storyteller

- Published

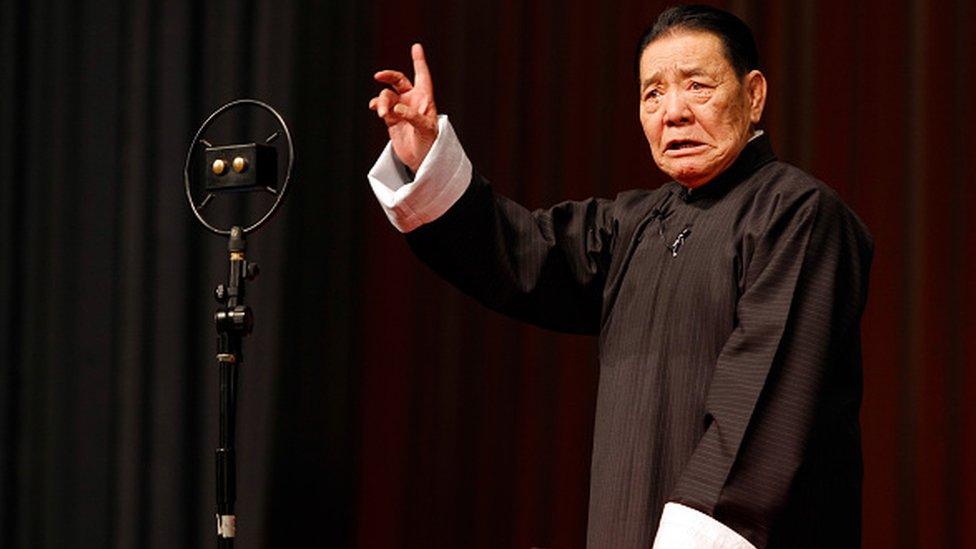

Shan Tianfang

China is fondly remembering one of its most famous radio voices, a man whose vivid storytelling was a comfort to millions of people, from commuters stuck in traffic to restless teens struggling to sleep.

Shan Chuanzhong, better known by his stage name Shan Tianfang, was a leading exponent of the traditional Chinese performance art form pingshu, which translates as "storytelling".

He has died aged 84 following a long illness.Pingshu, also known as "shoushu" and "pinghua", dates from the Song Dynasty (AD960-1279), when performers would entertain villagers by telling stories in a particularly emotive style.

It remains particularly popular in north-eastern China. Performers wear traditional dress and use very basic props - often a folded fan and a gavel. The fan is used to indicate a character's physical movements, like drawing a sword, or hitting something. The gavel is pounded for dramatic effect to indicate a moment of high drama.

Pingshu is sometimes performed in tea houses and small theatres, but many Chinese associate the art form with radio. And in a country where sleeping problems are commonplace, pingshu is still popular as a way of helping people to wind down at bedtime.

Shan's daughter Shan Huili thanked fans for their tributes soon after his death on 11 September, saying: "Although he has passed away, his voice will always accompany everyone, and his works will last forever."

Early years

Shan's voice captivated radio audiences, especially during the 1980s

Shan Tianfang was born in 1934 in Yingkou, in north-eastern Liaoning province. His family introduced him to folk arts from a young age and he began learning pingshu when he was 19.

He became known in Liaoning for his work on stage and in local teahouses during the 1950s and 1960s, and performed in an art troupe around the region.

But because of its associations with imperial China, pingshu was deemed taboo during Mao's Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976, meaning that Shan, along with other pingshu performers like Yuan Kuocheng, was forced to stop work.

Shan was persecuted for his mastery of pingshu, which was seen as a hangover from a feudal era. He was detained for "reformation training" in 1968 and was released in 1970.

Pingshu is often performed in teahouses and small theatres

However, after the Cultural Revolution, pingshu enjoyed a new lease of life, especially during the 1980s.

Shan made the transition to state-run radio, and his captivating storytelling became comfort listening for people across the country.

The popularity of the broadcasts was helped by the growth in consumer spending in the 1980s and the increasing availability of listening devices, including personal stereos.

Move towards television

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

By the 1990s, Shan had become a well-known face on state TV, even performing in the coveted annual Spring Festival Gala show, the single most-watched programme in mainland China.

He was able to use the medium to entrance his audience and in the process he helped to popularise classical Chinese literature.

As film director Zhang Jizhong told the Global Times newspaper: "He could describe a scene and a character extremely vividly. He once had a long talk with me about adapting the heroic stories he told into films or television shows to help promote Chinese classics and traditional culture."

Shan gave countless performances of the "Four Classic Novels" (Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, Dream of the Red Chamber and Water Margin), and also helped to bring lesser-known classical Chinese literature to new audiences.

One of his most acclaimed performances is of the Heroes in the Sui and Tang Dynasties, a historical and romantic saga about rebellious soldiers during the brief AD581-605 Sui Dynasty, and how they overcame the persecution of the emperor.

His stories attracted people of all ages, and grieving fans posted tributes to the late storyteller after his death.

One user on China's Twitter-like Sina Weibo service wrote: "When I was young, I remember hearing on my father's radio a compelling sound and a slightly hoarse voice. In the last two years, I have found myself listening to a lot of audiobooks on my mobile phone. You [Shan] have really been by my side for over 20 years."

But in his later years, the growth of online and digital media exposed the challenges of keeping his art form alive.

More lives in profile

Shan turned his efforts towards writing books and opening performance schools dedicated to teaching pingshu to young people.

They included the Shan Tianfang Culture and Media Academy in Beijing, which he founded in 1995.

A Shan Tianfang teahouse and "storytelling base" in Anshan in Liaoning province are devoted to his teachings. This is where many of his performances took place in the 1950s and 1960s.

Meanwhile, modern productions of pingshu reference contemporary culture to draw in new performers and audiences.

Performers like Guo Heming have emerged, putting a modern spin on pingshu by adapting popular works, including the Harry Potter stories.

Health problems

Shan helped keep his art alive by teaching pingshu to young students at his Beijing academy

Shan performed over 12,000 stories on TV and radio. And although he wasn't particularly active on social media, he amassed more than one million fans on the Sina Weibo platform.

His health began to decline in 2014, when he was diagnosed with a blood clot in the brain, and started to show symptoms of aphasia, a condition commonly associated with a stroke.

In an interview with state-run CCTV-10 in June 2017, he described how he was having increasing trouble with his speech.

"After [the blood clot], learning to say 'one, two, three', I couldn't say anything. I couldn't even say 'one'. How did this feel? It felt like I was finished."

Shan became a wheelchair user, but continued to visit his academy and help students learn the art of pingshu until his death on 11 September. State media said he had died as a result of his long illness. His daughter says he died without pain, with family members at his side.

A memorial was held for him on 15 September but millions of Chinese will miss his voice.

As one fan wrote: "Now that Tianfang has gone, I feel as though something is missing in my life.

"I have spent many nights listening to his stories, and they help me sleep… Tianfang is deeply rooted in our lives."