Obituary: Suman Virk, the mother who forgave her daughter's killer

- Published

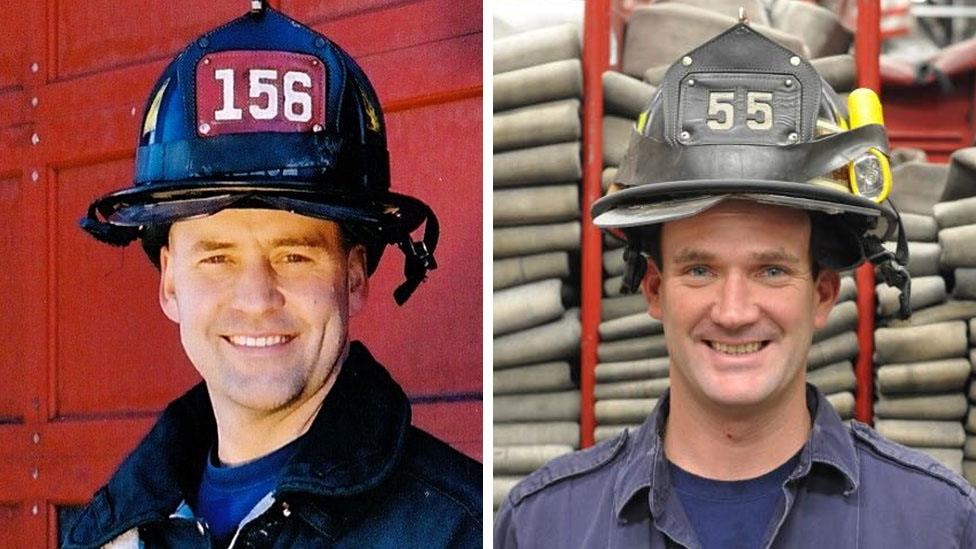

Suman and Manjit Virk campaigned against bullying across Canada

This article contains details some people may find distressing

In June 2007, 10 years after Warren Glowatski murdered her daughter, he turned to Suman Virk and hugged her. Glowatski, who had just learned he would soon be released from prison, then shook the hand of Virk's husband, Manjit.

It wasn't the first time they had met. The Virks had attended his trial and later, in a church basement, they had all taken part a restorative justice session - in which victims' families and the offenders meet face-to-face.

There, Glowatski apologised for killing their daughter, Reena, who was 14.

In November 1997, he was one of a group of 16 teenagers who swarmed around Reena. A number of them started assaulting her, and others stood by. Most of the attackers were girls, and the eldest was only 16.

In the initial assault under a bridge, Reena was burned by cigarettes, beaten and had her hair set on fire.

Afterwards, Glowatski and Kelly Ellard, 15, went after Reena and continued to beat her, inflicting a serious head injury. They then threw her into a river, where she drowned.

When Glowatski was freed in 2007, Suman Virk spoke of the importance of forgiving him.

"He was an angry, scared little kid who was trying to prove something in a negative way," Suman Virk told the gathered media.

"Today I think we see a young man who has taken responsibility for his actions and is trying to amend the wrong that he did."

Suman Virk's message of forgiveness was repeated across Canada this week after her death at the age of 58. Reports said she died after choking in a restaurant.

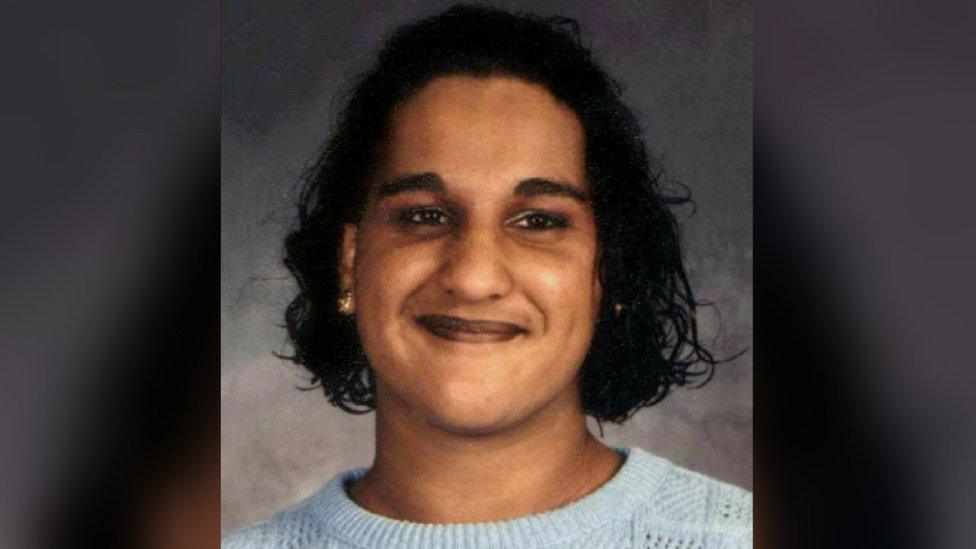

Reena Virk's body was found a week after she disappeared

Several aspects of the murder proved shocking to people across Canada. The unprecedented violence of the attack. The involvement of so many young girls. The fact that everyone involved kept quiet about it for a week while police searched for a body. The fact it took place in a largely middle-class area of Victoria, on the idyllic Vancouver Island.

"It was just completely shocking, partly because, for Canadians, it is considered where we go to retire or on your vacation," Rebecca Godfrey, the author of Under the Bridge, a comprehensive chronicle of Reena Virk's murder, told the BBC.

"There had never really been anything like this - it was before Columbine. The notion of teenage kids killing, particularly teenage girls, was unfathomable."

Suman Pallan had grown up on Vancouver Island after her father Mukand moved there from India's Punjab region in 1947. In 1979, she met Manjit Virk while he was on holiday in Victoria visiting his sister.

They settled in View Royal, a green, waterfront suburb of Victoria, British Columbia's regional capital. On 10 March, 1983, the first of their three children, Reena - whose name meant "mirror" - was born.

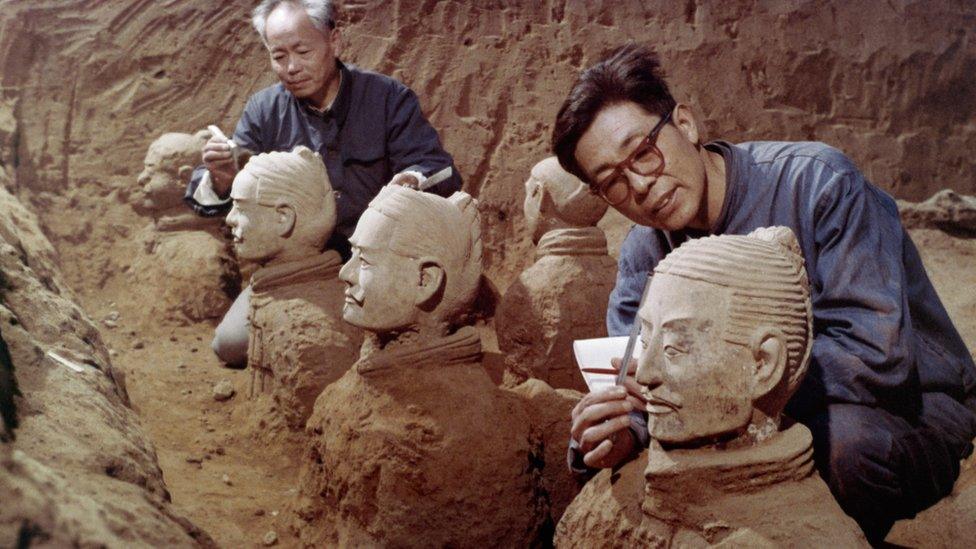

The murder happened in a suburb of British Columbia's provincial capital, Victoria

Reena was raised a Jehovah's Witness, which was unusual among the area's Indian community, and as a result she did not celebrate birthdays or Christmas.

In Under the Bridge, Rebecca Godfrey, who also grew up in Victoria, writes that Reena was increasingly frustrated with life as a Jehovah's Witness. She wanted birthday parties. She wanted to celebrate. And so she had been known to run away.

Reena was a loner desperate to fit in, and had been bullied throughout her life, Manjit Virk said in his book, Reena: A Father's Story. Bullies made fun of her weight and put gum in her hair.

At the age of 14, Reena stumbled across a group of young outsiders smoking at a park and felt immediately at home. She felt closest to Josephine Bell, a pale, blonde 14-year-old who lived in a group home, idolised gangsters and boasted of stealing cars.

It would later emerge that Reena had, for reasons that are unclear, taken an address book from Josephine and had started calling numbers in it to speak to people. She called one boy repeatedly to ask him out. She called others and told tales about Josephine for fun.

It did not take long for Josephine to find out. She lured Reena close to the Craigflower Bridge, saying there was a party going on, before confronting and attacking her.

One of Reena's killers, Kelly Ellard, is now out on parole, and gave birth while in prison

Two of the friends who joined her - Glowatski and Kelly Ellard - went on to continue the attack. Both were found guilty of second-degree murder - Glowatski in 1999, and Ellard, after three trials, in 2005. Six teenage girls were also sentenced for their part in the attack.

A fourth trial for Ellard was averted in 2009 by a Supreme Court decision but the Virks, while expressing forgiveness to Glowatski for admitting his role, were frustrated Ellard did not acknowledge the part she played.

The 12-year legal process took its toll. "For so long, we were consumed with the legalities of dealing with a murdered child, the court prolonging the cases," Suman Virk told Canada's Global News in 2012, external.

"It's kind of like you put your feelings and grief on hold and I'm finding that now I'm feeling more of the impact, the emotions, the feelings."

Read about other notable lives

Soon after Reena's murder, the couple had decided to focus their energy on educating young people in Canada about what happened, and how to respond to bullying.

"As we healed from the grief and got past the pain, it slowly became evident to myself that we have to help the public become aware of the very real problem of teen violence around us," Suman Virk told CBC television in 1998.

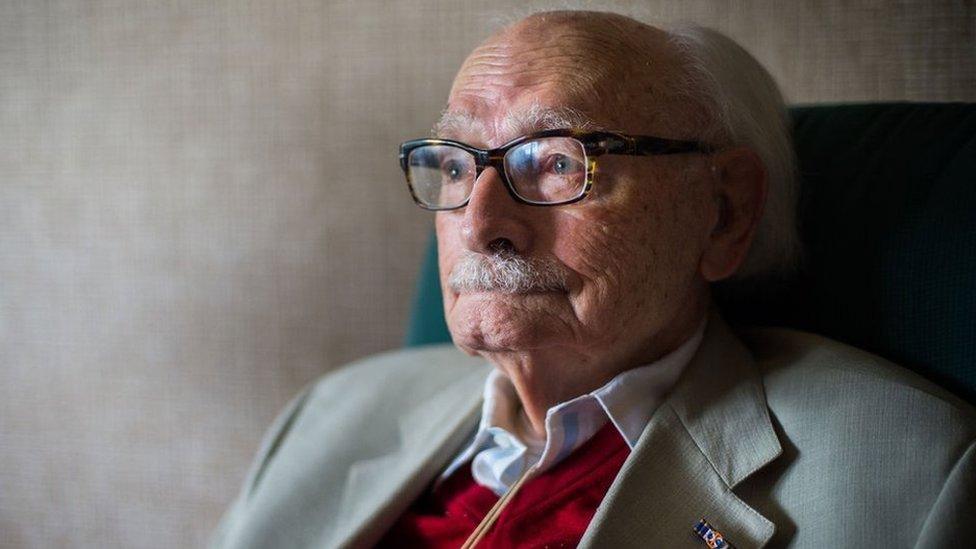

Suman Virk and her son Aman outside court after Kelly Ellard's first trial in 2000

In one video, Suman is seen speaking to students at a school. "Bullies thrive by you keeping quiet," she said in a calm, slow but firm voice. "That's how they get their power, if you don't talk about what's going on. It's too big for you guys to handle on your own."

There were "deep lessons to learn" from Reena's death, said Rachel Calder, the executive director of Artemis Place Society, a Victoria-based support group for vulnerable people. The Virks played a big part in teaching those lessons, she said.

"I am so honoured to have learned from them and the models they have been in the community," Ms Calder said. "They have spoken to thousands of schoolchildren about healthy relationships, friendships, how to treat people, how to treat diverse people from different backgrounds, where to go for help, how to forgive people."

John Horgan, the premier of British Columbia, echoed those comments in his own tribute.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Reena's death led to the creation of drop-in centres across the province for vulnerable youths, as well as the formation of a centre at the University of Victoria focusing on issues affecting young people.

But in 2012, Suman Virk acknowledged that bullying remained a significant problem, even if the methods of identifying it and responding to it had improved.

"I'm sad to say that the severity and the frequency of bullying is increasing and not decreasing," she told Global News. "We are all shocked at the means that young people are using to bully their peers, with cyber-bullying and texting that were not there when Reena was killed."

Suman Virk with her parents outside court in Vancouver in 2005

Problems that the murder highlighted - particularly that of troubled children with absent parents - were not addressed, Rebecca Godfrey said. And in some cases, outreach services were cut, she added.

However, the Virks' support for "a stronger, more compassionate resolution" between victims and criminals lives on, Rachel Calder said.

"It speaks to Suman and Manjit's capacity for love that they could have participated in this process of forgiving Warren and send him on his way in life with their blessing, through their empathy and compassion for him."

If you have been affected by the issues in this article, you can contact organisations that can help here (UK only)

- Published26 May 2018

- Published30 March 2018

- Published18 March 2018

- Published25 March 2018