He Jiankui defends 'world's first gene-edited babies'

- Published

Prof He's university has denied any knowledge of the research, which has not been peer-reviewed

A Chinese scientist who claims to have created the world's first genetically edited babies has defended his work.

Speaking at a genome summit in Hong Kong, He Jiankui said he was "proud" of altering the genes of twin girls so they could not contract HIV.

His work, which he announced earlier this week, has not been verified.

Many scientists have condemned his announcement. Such gene-editing work is banned in most countries, including China.

Professor He's university - the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen - said it was unaware of the research project and would launch an investigation. It said Mr He had been on unpaid leave since February.

Prof He confirmed the university was not aware, adding he had funded the experiment by himself.

What has the scientist claimed?

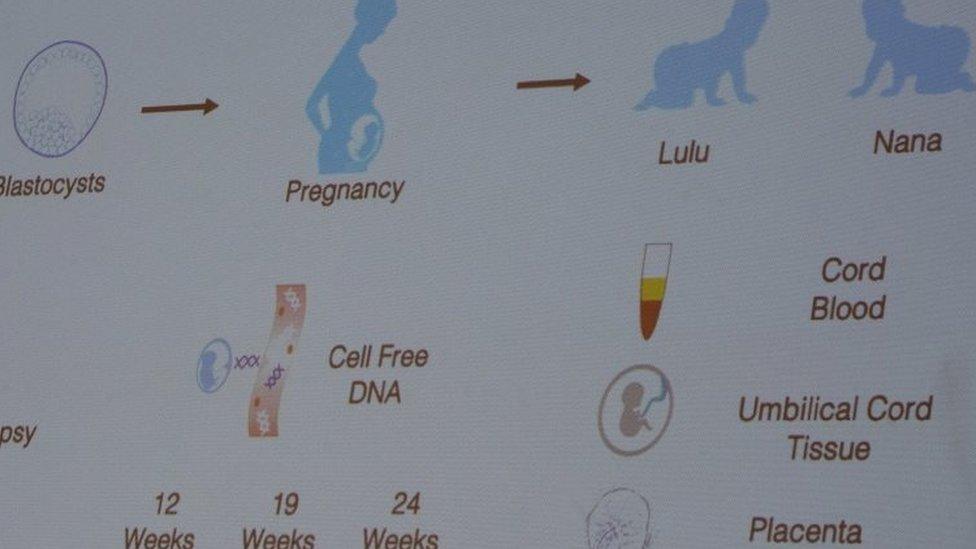

Prof He announced earlier this week that he had altered the DNA of embryos - twin girls - to prevent them from contracting HIV.

On Wednesday, he spoke at the Human Genome Editing Summit at the University of Hong Kong for the first time about his work since the uproar.

He revealed that the twin girls - known as "Lulu" and "Nana" - were "born normal and healthy", adding that there were plans to monitor the twins over the next 18 years.

He explained that eight couples - comprised of HIV-positive fathers and HIV-negative mothers - had signed up voluntarily for the experiment; one couple later dropped out.

Prof He has defended his work after widespread condemnation by the scientific community

Prof He also said that the study had been submitted to a scientific journal for review, though he did not name the journal.

He also said that "another potential pregnancy" of a gene-edited embryo was in its early stages.

But he apologised that his research "was leaked unexpectedly", and added: "The clinical trial was paused due to the current situation."

What do experts make of the claim?

By Robin Brant, BBC News, Hong Kong

No-one really knew if he was going to show. The auditorium was packed by the time He Jiankui walked on stage. This is the man who says he has given China a world first.

The handful of experts I spoke to, after they'd sat and listened to him, said they believed him. They believe this happened. But the big, big problem was that his speech and answers afterwards were scant on detail.

At times he was evasive, failing to give anything like the detail about his work - what he did, how he did it, who knew - that is required of any scientific project wishing to be regarded as credible.

He talked about the stigma attached to HIV/Aids in China and how important the family is to society, but he didn't give the names of "some experts" he claimed had reviewed his work and offered feedback.

Why is it this controversial?

The Crispr gene editing tool he claims to have used is not new to the scientific world, and was first discovered in 2012.

It works by using "molecular scissors" to alter a very specific strand of DNA - either cutting it out, replacing it or tweaking it.

Gene editing could potentially help avoid heritable diseases by deleting or changing troublesome coding in embryos.

But experts worry meddling with the genome of an embryo could cause harm not only to the individual but also future generations that inherit these same changes.

Prof He's recent claims were widely criticised by other scientists.

Hundreds of Chinese scientists also signed a letter on social media condemning the research, external, saying they were "resolutely" opposed to it.

"If true, this experiment is monstrous. Gene editing itself is experimental and is still associated with off-target mutations, capable of causing genetic problems early and later in life, including the development of cancer," Prof Julian Savulescu, an ethics expert at the University of Oxford, told the BBC.

"This experiment exposes healthy normal children to risks of gene editing for no real necessary benefit."

Many countries, including the UK, have laws that prevent the use of genome editing in embryos for assisted reproduction in humans.

Scientists can do gene editing research on discarded IVF embryos, as long as they are destroyed immediately afterwards and not used to make a baby.

Prof He's experiment is prohibited under Chinese laws, Deputy Minister of Science and Technology Xu Nanping told state media.

China allows in-vitro human embryonic stem cell research for a maximum period of 14 days, Mr Xu clarified.

- Published26 November 2018

- Published6 June 2016

- Published30 August 2018