Gene editing technique could transform future

- Published

Fergus Walsh: "CRISPR gene editing .... uses molecular scissors to cut both strands of DNA"

CRISPR - get to know this acronym. It's good to know the name of something that could change your future.

Pronounced "crisper", it is a biological system for altering DNA. Known as gene editing, this technology has the potential to change the lives of everyone and everything on the planet.

A bold statement but that is the considered view of many of the world's leading geneticists and biochemists I've spoken to in recent months when working on my latest Panorama - Medicine's Big Breakthrough: Editing Your Genes.

CRISPR was co-discovered in 2012 by molecular biologist Professor Jennifer Doudna whose team at Berkeley, University of California was studying how bacteria defend themselves against viral infection.

Prof Doudna and her collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier are now among the world's most influential scientists. The natural system they discovered can be used by biologists to make precise changes to any DNA.

She told me: "Since we published our work four years ago laboratories around the world have adopted this technology for applications in animals, plants, humans, fungi, other bacteria: essentially any kind of organism they are studying."

When a bacterium comes under attack it produces a piece of genetic material that matches the genetic sequence of the invading virus.

This piece of material in tandem with a key protein called Cas9 can then lock on to the DNA of the virus, break it and disable it.

Scientists are now able to deploy the same process to insert, delete or repair DNA.

It is so sensitive that they can use it to explore the billions of chemical combinations that make up code of the DNA in a cell, and to make a single key change.

Crucially, it is fast and cheap, and so is accelerating all kinds of research, from the creation of genetically-modified animal models of human disease to the search for the DNA mutations that trigger illness or confer protection.

Professor Jennifer Doudna: "Once one understands the sequence of DNA in a cell it's possible to rewrite it."

So how and when might we begin to see treatments from CRISPR? Given that the technology is just a few years old it is not surprising that trials have yet to begin in patients, but several are in the planning stage.

The Boston biotech firm Editas Medicine, external is hoping to have a gene-editing treatment ready for clinical testing in 2017 to treat Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA10), a rare retinal disease that causes blindness. The gene mutation causes the gradual loss of photoreceptor cells in the eye.

Cancer target

There are several recently-formed biotech firms which are hoping to take CRISPR technology into the clinic.

They are working on the theory that CRISPR might be used to boost the function of the body's T cells so that the immune system is better at recognising and killing cancer. Disorders of the blood and immune system are other potential targets.

One cloud hanging over all this effort is a big patent fight over CRISPR. On one side are Prof Doudna's team, on the other a group based in Boston, Massachusetts.

The patent row is unlikely to prevent academic researchers from using CRISPR, but it could have a profound impact on who reaps the financial returns of this emerging technology.

Two earlier forms of gene editing have already made it into the clinic.

Last year a technique known as TALENs was used to help reverse cancer in a patient at London's Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Layla's mother, Lisa: "There's always got to be a first... we begged them to try something"

Layla Richards had an aggressive form of leukaemia, and all previous treatments had failed. She remains the first person to date whose life has been saved by gene editing.

The world's first gene-editing trials took place in California, involving a different technique, ZFNs, external. Around 80 patients with HIV had immune cells in their blood removed.

Scientists then deleted a gene called CCR5 which HIV uses to gain entry to cells. The treatment is based on a rare, gene mutation which gives some people a natural immunity to the disease.

Matt Chappell had his immune cells gene edited

One of the volunteers was Matt Chappell, 52, who has lived with HIV most of his adult life and witnessed the devastating impact that HIV/Aids has had on the gay community in San Francisco.

Matt has been off all antiretroviral medication for two years since having his immune cells gene edited.

These were small trials so caution is needed before reading too much into the results, but they are nonetheless extremely promising.

The HIV treatment was created by Sangamo Biosciences of Richmond, California, which has the exclusive licence for ZFN technology.

The company is about to begin patient trials in the serious blood-clotting disorder haemophilia and is also working on a treatment for beta thalassemia.

The most controversial aspect of gene editing concerns the potential to introduce changes to the germline - DNA alterations that would pass down the generations.

In theory it might be possible to correct the DNA of embryos carrying the gene for Huntington's disease or cystic fibrosis.

But it might also be used to add in genetic enhancements, leading to designer babies.

Human embryos

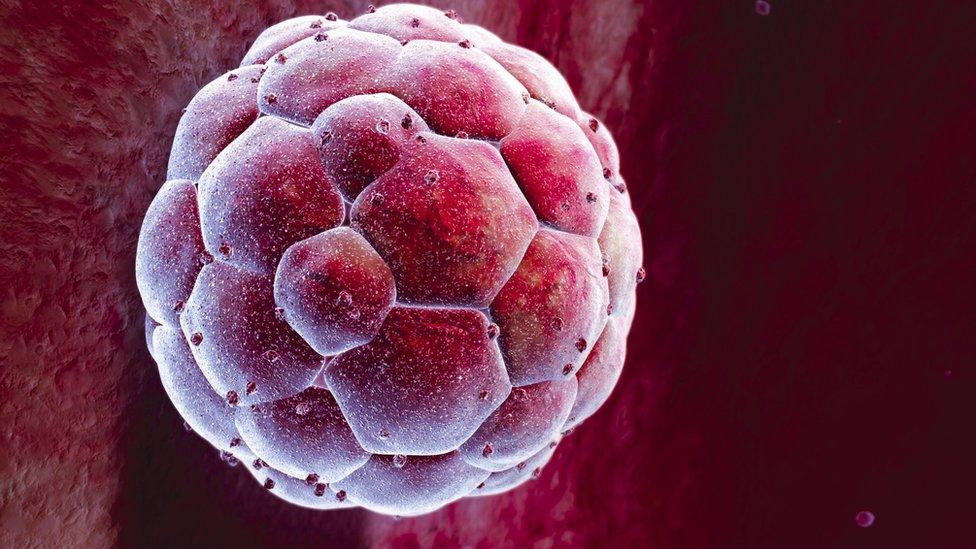

No scientist is suggesting - yet - that gene-edited human embryos should be born. But several teams in China have done some basic research and the UK is the first country to formally approve gene editing in human embryos, for research only.

The HEFA is the first body in the world to sanction embryo gene editing, as Fergus Walsh reports

This will be done at the Francis Crick Institute in London. When it opens in a few months it will be the biggest biomedical laboratory in Europe and will be a centre for gene editing.

A team led by Kathy Niakan - recently named by Time magazine as one of the world's 100 most influential people - will use CRISPR to edit out key genes from the embryo, to try to identify the genetic faults which lead many women to repeatedly miscarry. The embryos will be allowed to develop for just a few days.

She told me: "What I'm hoping is that it provides us with a really crucial insight into early human development.

"I think it could help in identifying ways in which we could improve IVF to identify those embryos that are likely to continue to develop and thrive and, and give rise to healthy babies."

Ethical concerns

But this research rings ethical alarms bells for Marcy Darnovsky of San Francisco's Center for Genetics and Society.

She believes human embryo editing research may not be adequately controlled, leaving it open to a lab somewhere to create the first gene-edited babies.

"You could find wealthy parents buying the latest offspring upgrades for their children. We could see the emergence of genetic haves and have nots, leading to even greater inequality than we already live with."

Some of the key scientists in this field have concerns about the potential misuse of a technology that could be used for eugenics, to create genetic discrimination.

Prof Doudna told me of a nightmare she had where she was led into a dark room where a man was seated with his back to her.

She said: "When he turned I realised with horror that it was Hitler and I was being expected to discuss this technology with him and he eagerly wanting to use it."

She says that that while it is very hard to regulate the use of CRISPR technology, it is important to find a consensus about how people should proceed.

"I never want to over-promise but I feel diseases will be cured and we want to enable clinicians and scientists to bring that to a reality."

Panorama - Medicine's Big Breakthrough: Editing Your Genes will be shown on BBC World News at these times. It was first broadcast in the UK on 6 June 2016 and is available to watch in the UK on BBC iPlayer.

- Published1 February 2016

- Published3 December 2015

- Published1 December 2015

- Published5 November 2015