A woman's murder in Peking and a literary feud

- Published

On a cold January evening in 1937, the 19-year-old adopted daughter of a former British diplomat in China left her friends, got on her bike and rode to her death. Her murder sent shockwaves through Beijing - then known as Peking - but arguments about the gruesome, unsolved crime echo to this day.

WARNING: Readers may find some of the descriptions of violence in this story distressing.

There was every reason for the killing of Pamela Werner to simply fade into history until a book introduced the case to a modern audience in 2011. But Paul French's best-seller Midnight in Peking also dug up old ghosts and animosities which ran much deeper than the writer could have envisaged.

A retired British policeman, Graeme Sheppard, has now written a rival book challenging French's version of events.

The result: a literary stand-off revolving around family pride, bizarre events now lost in the past and a grisly murder still unsolved.

The killing

On the evening of her death, Pamela had been ice-skating with friends in the foreigners-only Legation Quarter of Peking. She was due to leave for London in a few days to pursue further studies.

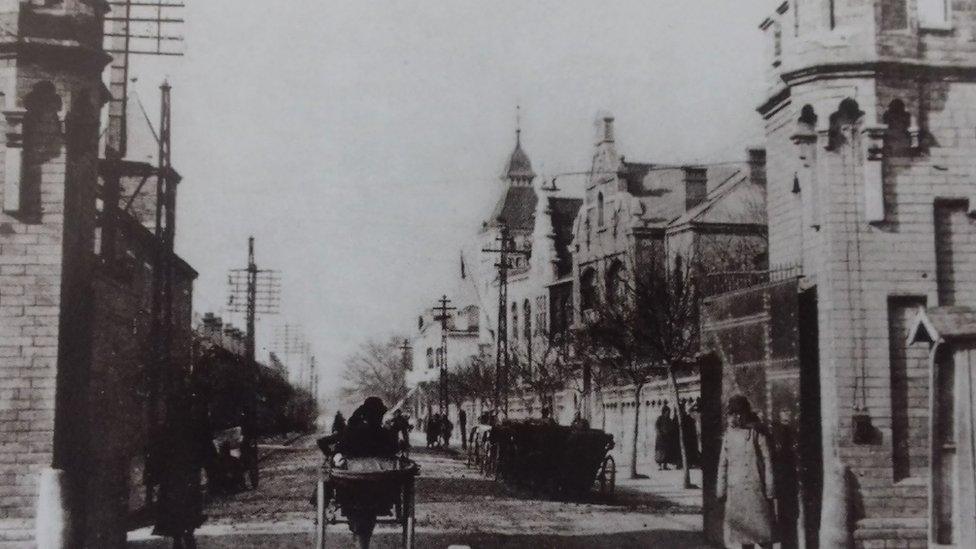

The exclusive Legation Quarter was home to foreign diplomats and off-limits for most Chinese residents of Beijing

She left her friends at about 7pm. They would never see her again.

Her body was found the following morning on frozen ground next to the only surviving section of the city's Ming Dynasty wall.

What investigators then and now have struggled to understand was the motivation for the severe mutilation of her body. Organs had been removed, ribs broken. Her heart, bladder, kidneys and liver were gone.

Her throat was cut in what could have been an unsuccessful attempt to remove her head. Her right arm remained attached but only just.

Whoever did this was either sloppy or had been interrupted and left quickly, because crucial evidence was at the site when police arrived.

They found Pamela's skate rink membership card and an expensive watch which once belonged to her mother. It had reportedly stopped at a couple of minutes past midnight. This meant she could be identified quickly despite the state of her corpse.

Newspapers from the time reveal the distress the news caused as details reverberated across a city already on edge, with the Japanese army closing in.

If at this time of uncertainty and confusion a white woman - the adopted daughter of a noted British Sinologist - could be disposed of in such a fashion then who was safe, especially given that she had grown up in what is now central Beijing, spoke Chinese, knew her way around and that her remains were found just a short walk from her home?

A world of mystery and ill will

Peking's population had been swelling with people fleeing as parts of China fell to the Japanese. There were also Russian refugees escaping turmoil and civil war in their own homeland. Among them had been Pamela's birth parents.

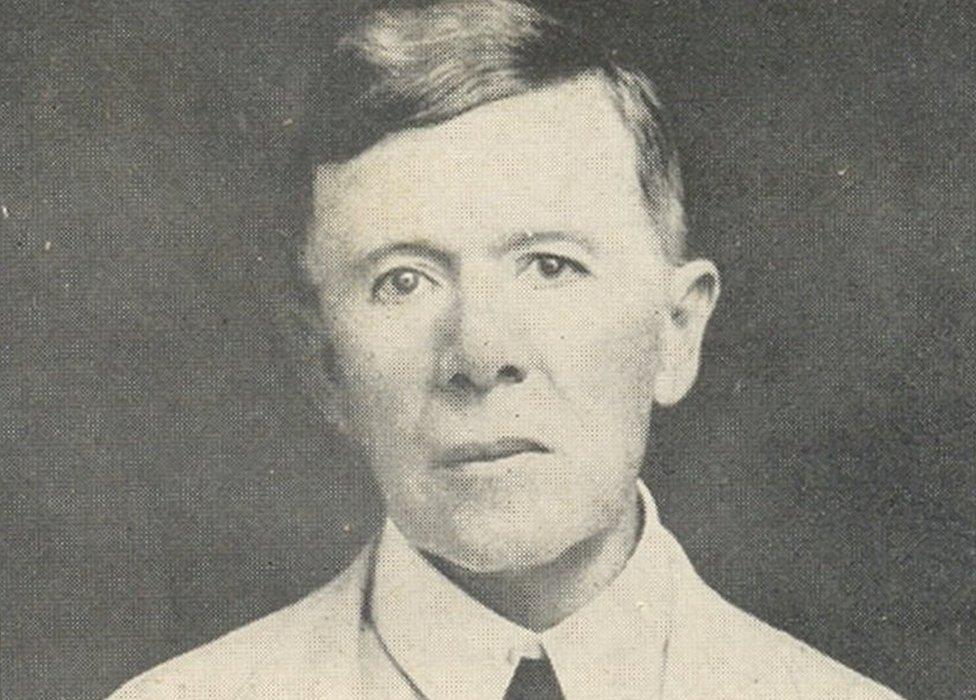

Edward Werner spent his final years searching for clues about his daughter's death

She was adopted by the Werners at the age of two but her adoptive mother had died when Pamela was five.

After Pamela's murder, her father Edward Werner - then in his 70s - was left to solve a grisly crime alone and with a broken heart. He spent the rest of his life searching for the killers and his quest would produce voluminous correspondence to officials in China and also back in London.

When Paul French stumbled across this material in the British national archives he burst open a world of mystery and ill will.

The letters formed the basis of his book, which is really an exploration of what happened through the lens of Pamela's father. The runaway success of Midnight in Peking has also meant that this became, for many, the accepted version of events.

But when Graeme Sheppard read it he had personal reasons for taking issue with this explanation. Following his own dive into the archives, he has now written A Death In Peking, presenting a very different hypothesis.

Both writers agree that the official cause of death, a blow to the skull, was almost certainly correct. But when it comes to the identity of the killer, or killers, the location of the murder, the motivation and crucially how her body came to be found where it was, they diverge quite radically.

The sex party

Pamela's father believed his daughter had been lured to a party that night, in all likelihood with other young women.

"We would probably understand this now as grooming," French told the BBC.

French believes Pamela was killed during a debauched party that went wrong

"They wished to use these women for sex. When Pamela realised what was happening something went wrong. It seems that she might have been hit on the head with something that cracked her skull and these men were left with a dead body they had to deal with."

Given the seedy goings on in 1930s Peking, French says he can imagine how the evening may have unfolded with Pamela unwittingly getting in over her head, fuelled by the excitement of her final days before leaving the city she loved.

After ice skating she is thought to have had dinner first with a student friend who would become crucial in Graeme Sheppard's theory.

However, according to Paul French, the next stop was a party at the home of American dentist Wentworth Prentice.

As foreigners with special privileges, largely unchecked and moving around a chaotic city in the dying throes of an era, Prentice and his cabal of mates are described as leading a debauched, hedonistic lifestyle.

The notorious 'Badlands' lay just north-west of the city's train station

Pamela would not necessarily be expected to fear those at the dentist's flat. She had been a patient of his and probably knew others there as well.

So when it was announced that the party would kick on to a bar in celebration of Russian Orthodox Christmas why not? Even if it was to be in the brothel neighbourhood known then as "the Badlands".

If you walk just west of Beijing station and then go north you can explore this area. The streets are much quieter today, apart from the little family-run hotels in the old courtyard houses, but apart from that they have not changed that much since 1937.

It was here that French says Pamela would have found herself alone with this group of men. There was no party, just a bed in the back of a brothel.

He writes: "Perhaps her resistance, her refusal to submit as other girls had done before her, angered the men… Perhaps they panicked and just wanted to shut her up… to silence her one of the men hit her hard on the head."

Pamela's father would later visit the brothel, called only Number 28, on his hunt for the killers.

He estimated that she died there but was then moved elsewhere for disposal on the orders of the establishment, which wanted nothing to do with this.

He paints a picture of men who drained her blood at the brothel to make her lighter to move, then wrapped her up and took a rickshaw to the old city wall: a place with no streetlights and where passers-by were unlikely to be seen.

There they would carve up the body.

These might sound like extreme measures but, according to French, those involved were hunting comrades. Here he's relying on the view of Pamela's father who saw them as a strange group known for their nudist parties in the western hills of Peking. Apart from the sex, booze and drugs there was deer hunting and butchery too.

"This seemed to Werner at the time, as symptomatic of how hunters would deal with a deer or another animal," French says.

"They all had knives. This seems to me to be a plausible explanation and is backed up by many people, including people at the time."

He writes: "They would dismember [the body] and dump the parts outside the Legation Quarter, shifting suspicion away from themselves and making the body impossible to identify. It would be seen as the work of a fiendish maniac, most probably Chinese."

The rival theory

Graeme Sheppard takes issue with almost all of French's - and by extension Edward Werner's - conclusions. He barely mentions his fellow British writer but his book is essentially an attack on French's central thesis.

Sheppard's book points the finger of blame at a close friend of Pamela's

"It was a popular book, good to read, made for a good story but, from a policing perspective, it didn't make sense," Sheppard told the BBC. "I couldn't see how the British and Chinese police had missed suspects that the father had found.

"In an area as small as the Legation Quarter here in Beijing, it didn't make sense to me."

With his old police hat on, the Sheppard thesis is that there is no evidence to suggest that Pamela would have been the type of young woman to end up in a Badlands brothel, even if she did know some of the men.

His idea is that the killer met Pamela soon after her skating trip, and he points the finger at somebody once close to her heart.

"I think the strong likelihood is that it was a former Chinese school friend of Pamela's by the name of Han Shou-ching," he told the BBC. "And the reason I think that is that the British chief inspector overseeing the case was absolutely convinced of the fact."

Sheppard says there would have been police intelligence at the time informing the chief inspector's beliefs.

But French dismisses the idea of relying on police suspicions, adding that there is no record of them ever interviewing him.

"To assume that a teenage student who was dating her would suddenly decide to murder her, drain all her blood, mutilate her and then disappear, never to be questioned by the police in their investigations, seems to me frankly bizarre," he said.

However Sheppard counters that it is indeed plausible to assume his suspect would have known butchery skills and routinely carried a knife.

More true crime stories from the BBC

He also thinks it is possible that the student could have killed her and then others later came along and removed her body parts to sell for various superstitious Chinese medicine practises in place at the time.

But his source for the chief inspector's convictions regarding this student is also the letters of Pamela's father.

Critics might point to the inconsistency of being dismissive of so much of Edward Werner's analysis and then relying so heavily on the former diplomat's characterisation of the inspector.

One thing is true though, Pamela's father did write about punching Han Shou-ching on the nose for what he suspected was an amorous relationship with his daughter. So maybe there was some tension building there?

The family ties

Either way French's main criticism of Sheppard is that he is not impartial.

Sheppard's wife's grandfather was Nicholas Fitzmaurice who - as British consul general at the time of the murder - ran the inquest which ended in an open finding.

Pamela's father, a former diplomat, already had a testy relationship with Mr Fitzmaurice and the consul's failure to find his daughter's killer would have only intensified the acrimony.

Generations later it is as if this feud is still being fought out. The descendants of Fitzmaurice were angry at how he was portrayed by Paul French as a bit of a "stuffed shirt", useless bureaucrat. Although she never met her grandfather, Sheppard's wife felt the need to defend his reputation and drew her husband's attention to the case.

But Sheppard says this was only the spark leading him to the story and that his work is the result of his own extensive research, also drawing on material French did not use.

Japanese troops with Chinese prisoners in what is now Shandong, China

He has come up with a portrayal of Edward Werner as an isolated, "quarrelsome" figure who was "suspicious of others" and paid informants for evidence.

The ill will between two British diplomats goes back a long way. They had an argument 110 years ago about whether Chinese historical artefacts should be taken back to London. French says Fitzmaurice said he'd take them, but that Werner argued to leave them in China with British government assistance.

Decades later, Werner finds himself presenting evidence in front of a man he - in all likelihood - already despises on philosophical grounds and he ends up writing to London condemning the handling of the inquest.

Under Japanese guard

A sad postscript to all of this is to be found a long way from where these incidents took place.

In 1943, with the Japanese army in control much of China including Peking, foreigners were rounded and sent to detention camps. Edward Werner not only had to leave behind his worldly possessions but also the investigation into his daughter's death.

Then, behind the barbed wire in Shandong Province, he found himself in the company of the very men he suspected of killing his daughter, including the dentist Wentworth Prentice. He was working on the teeth of others in the camp using whatever equipment he could pull together.

Paul French writes: "Some inmates recalled him pointing at Prentice and calling out, 'You killed her. I know you killed Pamela. You did it'. At other times he seemed to point at people at random. Some feared for his sanity but he was forgiven his odd behaviour."

Pamela's final resting place is beneath one of the ring roads circling the capital

He would survive Japanese internment but, by that stage, in his 80s, could not convince the post-war British Foreign Office to retain much interest in the case. Prentice also returned to the Legation Quarter but he died there in 1947.

The student Han Shou-ching was murdered by Japanese military police, according to Edward Werner but Sheppard writes: "Perhaps that [report] was correct and perhaps not… Being purportedly dead may have been a clever ruse to keep the police from further pursuit."

Werner remained in China throughout the civil war and by October 1951 is said to have been one of only 30 British subjects still living in a Beijing now controlled by the Communist Party.

He returned to the Britain he had not visited since 1917 and outlived everyone else involved in the story. By the time he died, at the age of 89, there was apparently nobody left who knew him to attend his short funeral service.

As for his murdered daughter, she is buried deep somewhere beneath what is today Beijing's second ring road.