China birth rate: Mothers, your country needs you!

- Published

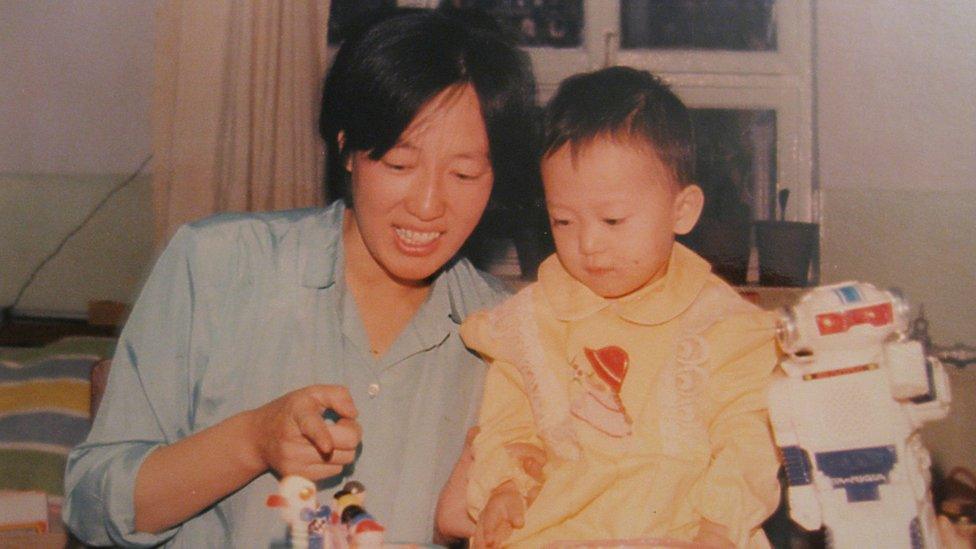

China is now trying hard to encourage women to have more children

When China ended its one-child policy three years ago, there was hope couples would have a second child to help slow the pace of an ageing society. But the move isn't working, reports London-based China analyst Yuwen Wu.

The declining birth rate is now one of the most talked-about topics across China - and there's a real sense of crisis.

After decades spent trying to curb the population, state propaganda slogans now exhort couples to "Have children for the country", prompting criticism on social media that government policy is intrusive and insensitive.

Measures now being discussed range from extending maternity leave to encouraging people to have a second child with straight cash incentives or tax breaks. Some are even calling for limits on the number of children to be abandoned altogether.

Aimed at curbing population growth, China's one-child rule was introduced in 1979, a year after economic reforms. The policy was strictly enforced for most people. Those caught violating the policy could be fined, lose their jobs or face forced abortions and sterilisation.

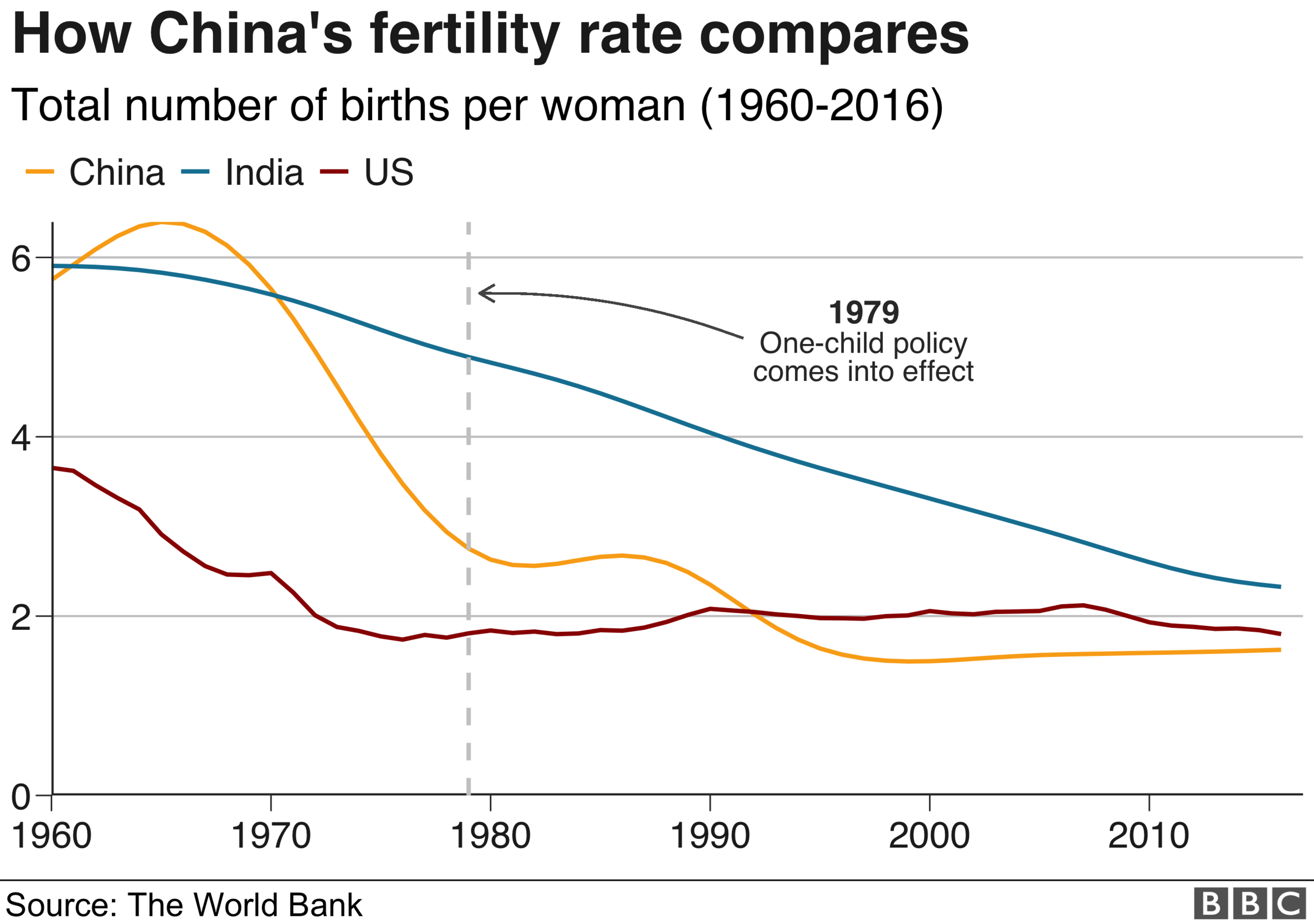

But the fertility rate had already gone into steep decline a decade earlier.

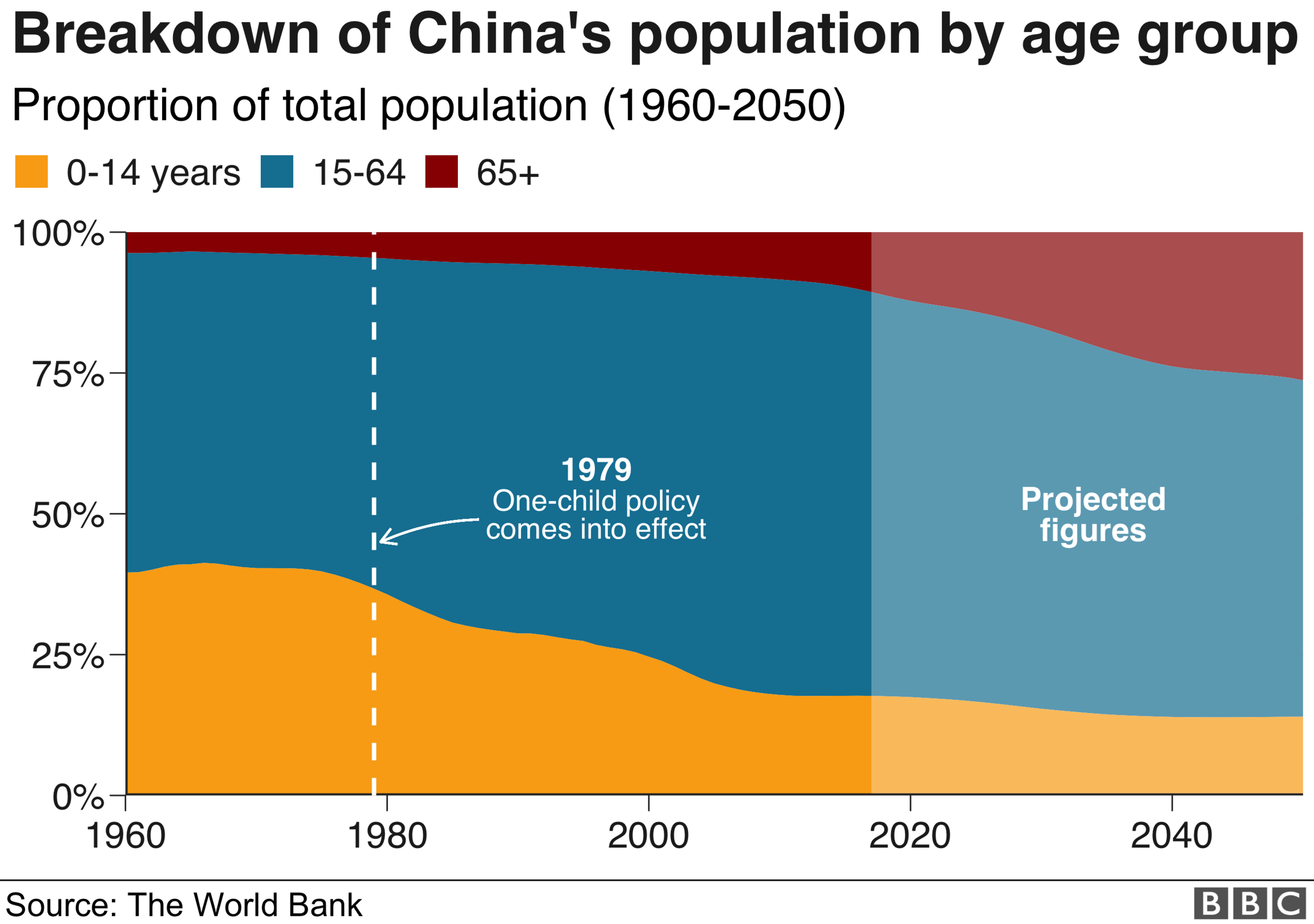

For years China benefited from demographic dividends - its massive population (almost a fifth of the world's) provided plenty of manpower - and manageable numbers of very young and old people - to fuel the country's rapid economic rise.

Now all that is disappearing, fast.

In order for China to continue its economic development and support its aged, the population needs to grow rather than decline.

The ending of the one-child policy in 2015 was meant to boost this, but the data suggests the opposite - despite the freedom to do so now, young people don't seem to want more children.

How big a problem is the low birth rate?

According to China's National Statistics Bureau, there were 17.86m births in 2016, and the Chinese population grew by 1.31 million, with a rate of 12.95 births per 1,000 people, the fastest since 2001.

But in 2017, which should have seen the full effect of the two-child policy, there were 17,230,000 births, a decrease of 630,000 compared with 2016; the birth rate stood at 12.43 per 1,000, down 0.52% from 2016.

This is below even the most pessimistic forecast before the new policy was introduced.

Predictions for the future look even bleaker:

The birth rate will continue to decline from 2018 onwards

In the next 10 years, the number of Chinese women aged 23-30 will decrease by 40%, a huge drop in this child-bearing age group

In 10 years' time, there will only be about 8 million births per year

Not surprisingly, the looming crisis has got everyone talking.

On 6 August, the Communist Party's official newspaper People's Daily devoted a whole page to the issue, including an op-ed entitled "Having children is a family matter but also a national matter", external.

The editorial warned that the state needed new policies to deal with the impact of the low birth rate on the economy. This prompted much coverage and debate in the media.

A Chinese state media outlet called having children a "national matter"

One article in Xinhua Daily - by two scholars from Nanjing University - sparked an outcry. They suggested a birth fund be set up, to which everybody below the age of 40 contribute. If a couple were to have a second child, they could withdraw money from the fund; if not, they would have to wait until retirement.

"Fined whether one has a child or not? - please stop targeting people's wallets," was just one of the articles in response to the idea, which has been labelled inconsiderate, unfair and unnecessary.

Some urged the state to address the root cause of why young people don't want more children and try to lower the cost of raising a child, rather than penalising people financially.

Why so urgent now?

China is fast becoming an ageing society.

As well as the birth rate falling, people now live longer - life expectancy was 66 when the one-child policy was introduced, external, and it is now about 76. This will put great strain on China's economy in the decades to come.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the number of people aged 15-64 topped 1 billion in 2013, but has been declining steadily since and will continue to do so.

At the same time, the number of old people is growing. In 2017, China's total population stood at 1.39 billion - including 158 million people aged 65 and over, constituting 11.4% of the population.

That's more than one and half times the UN's definition of an ageing society (when 7% of the population are 65+). The UN's 2017 Revision of World Population Prospects forecasts that 17.1% of the Chinese population will be over 65 by 2030, external.

This trend entails that old people are supported by fewer and fewer people of working age. According to an article by Ning Yi published on ifengweekly, there were 3.16 young people for each old person in 2011; by 2016, the age dependency ratio was down to 2.8. It is predicted that by 2050, it will be just 1.3.

As in other countries with similar age ratio projections, this has huge implications for the economy, for paying pensions and for meeting elderly care needs.

Why aren't people having more children?

Many young people in China who grew up during the three decades of strict family planning and break-neck economic development have a different mindset from their parents.

They are used to being the centre of attention and enjoying much better material wealth and personal freedom.

They are also marrying late (if at all), having children late (if at all), and focusing more on their own careers and happiness, a trend not confined to China.

More young people in China today no longer consider children to be their main priority

When they contemplate starting a family, one big concern is whether they can afford it.

Surveys show that on average, raising a child in a city can cost more than half of a Chinese family's income. Childcare places are always oversubscribed, so many have to rely on grandparents for help. And then there's the mortgage and other burdens on the family budget.

In other words, to have one child is a struggle; to have another needs even more resources and support.

None of the young people I talked to recently in China wanted a second child.

"Our generation has a tremendous burden on our shoulders," one woman, who did not want to be named for this article, told me. "Our ageing parents, our young children, our own careers. These combined together can easily crush us."

The woman, who is in her 30s, already has a five-year-old son, but she and her husband have decided not to provide him with a sibling. Lack of childcare is a big reason.

"So what often happens is we hire nannies to look after the baby, and ask our parents to keep an eye on the nanny."

How the one-child policy changed

China is finding it hard to encourage population growth

1979: Government proposal encourages all couples to have just one child

1982: Family planning becomes basic state policy

2000: A couple can have a second child, if both of them are only children

2013: Couples allowed to have a second child if one of them is an only child

2015: End of one-child policy and all couples are allowed to have a second child.

On the other hand, some older women, already in their early 60s, were quite firm that had the one-child policy ended earlier, they would have tried for another child, even up to their late 40s.

So, did the one-child policy go on for too long? And was there a robust enough national debate? Many people are now asking these questions.

Were China's leaders slow to act?

All censuses carried out after 1990 point to the rapid decline of the total fertility rate (the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime) in China, which is lower than the 2.1 needed as a replacement fertility rate.

But there has been fierce disagreement over the true figure. For instance, a population survey in 2000 indicated the total fertility rate was an alarmingly low 1.22; family planning officials, however, marked it up to 1.8, arguing many births were unreported. In the end, the authorities went with 1.8.

Might the difference mean that an otherwise urgent situation was downplayed and action delayed?

Some are asking if the one-child policy was allowed to go on for too long

Even today, one struggles to find an authoritative figure for China's current total fertility rate - some put it at 1.2-1.4; others between 1.5 and 1.7 - which is lower than in the US (1.8) or India (2.3).

Some did voice their concerns and call for changes to stem the decline in population growth, but little heed appears to have been paid.

More than a decade ago Ye Tingfang, a member of China's top political advisory body, the CPPCC (Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference) argued that it is against nature to intervene in the reproduction process. He tabled a motion at the 2007 People's Congress session, calling for an end to the one-child policy as soon as possible.

The State Family Planning Committee told him the country would not change the one-child policy. His follow-up petition met with silence.

Other dissenting voices include a book in 2012 entitled "Are there too many Chinese?" written by James Liang and Jianxin Li, two professors from Peking University.

They argued that China's birth rate had become too low, and if the trend continued, the country would age too fast, the economy would suffer and society would become unstable. They urged adjustment to family planning policy as well.

It is difficult to guess what went on behind the scenes with decision makers; the fact is, it was not until 2013 that we saw some relaxation of the one-child policy.

Do two children make you rich?

These days one thing that has changed is there does seem to be more open discussion about population matters in China.

In some places authorities have stopped collecting fines for children borne outside of the quotas.

Some experts propose using 2% to 5% of GDP to encourage births, through tax reductions and cash incentives.

Others say people should be allowed to have as many children as they want.

China's 2019 stamps, showing two parent pigs and three piglets, were interpreted by many as a way of encouraging couples to have more children

And there is a lot of propaganda - which people poke fun at.

"'One child makes you poor, two children make you rich' - it's too soon for such slogans, we need some breathing space!" shouts one netizen.

"'You regret if you don't have children, and you have nobody to look after you when you grow old' - this is so against what we were told growing up (to marry late and have fewer children). The change is too fast!" laments another.

Mock posters are doing the rounds, external too.

And this is really what has changed. Individuals happen to be more free-thinking now and independent - and not easily swayed by propaganda or lukewarm incentives.

They live for themselves, not for the country any more.

It turns out it is much harder to encourage population growth than to curb it - in the end, it's down to individuals to make the decision.

- Published18 December 2018

- Published10 August 2018

- Published30 October 2015