Yanxi Palace: Why China turned against its most popular show

- Published

Yanxi Palace - a danger to Chinese society?

It was one of China's most popular shows of 2018 - but it's now being pulled from TV screens across the country.

The story of Yanxi Palace, a drama about life in imperial China, broke records when it was released last year.

It was streamed more than 15 billion times on China Netflix-like iQiyi and became the most watched online drama in China for 39 consecutive days.

All that changed in late January when a state media article criticised the "negative impact" of imperial dramas, and it wasn't long before Yanxi Palace was taken off air.

So why has this blockbuster show fallen from grace?

'Bad for Chinese society'

It all started when Theory Weekly - a title linked to state newspaper the Beijing Daily - posted an article criticising period dramas and singling out Yanxi Palace in particular.

It listed several "negative impacts" these shows had on Chinese society, like propagating a luxurious and hedonistic lifestyle, encouraging admiration for imperial life and a glorification of emperors overshadowing the heroes of today.

The magazine named several other popular imperial period dramas, like Ruyi's Royal Love in the Palace, Scarlet Heart and The Legend of Mi Yue.

China wants entertainment to always also promote socialist values

Shortly after the piece was published, Yanxi Palace and Ruyi's Royal Love in the Palace were pulled from state-run TV channels.

The shows are, however, still available on iQiyi, the place that Yanxi Palace was initially produced for and was first shown.

Rival versions of history

"It's not the first time something like this has happened," Prof Stanley Rosen, a China specialist at the University of Southern California, told the BBC.

"But I would say the censorship is certainly getting worse.

"Yanxi Palace was seen as promoting incorrect values, commercialism and consumerism; not the socialist core values that Beijing wants to see promoted."

"For those who are overseeing those productions there should always some educational value or some promotion of Chinese cultural values or some sort of historical narrative that matter," explains Manya Koetse, editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo,, external a website tracking Chinese social media.

Prof Zhu Ying of the Film Academy at Hong Kong's Baptist University told the BBC. "Censors tend to turn a blind eye to entertainment programs of frivolous nature.

"But that's only until they become too popular and threaten social norms, morally and ideologically. Yanxi is a perfect example of such a show."

Given the popularity of Yanxi Palace, the Theory Weekly article unsurprisingly became a widely debated topic on the internet - and with most comments condemning the critique, authorities were as little pleased with the online debate as with the series itself.

One post, by online news website Phoenix, was shared more than 10,000 times and had more than 32,000 comments, Ms Koetse explains. All of those comments have since been blocked and the entire comment section is turned off.

"The fact that most comment sections have been locked/shut down for now is quite telling," she says.

Too successful abroad?

Another problem might have been the attention Yanxi Palace received from international audiences.

"It could be that the show became too popular outside China," says Mr Rosen. "It's a contradiction of wanting to succeed overseas but also wanting to control the message."

Beijing wants Chinese culture to be promoted outside of China but showing the values that the authorities want to see portrayed.

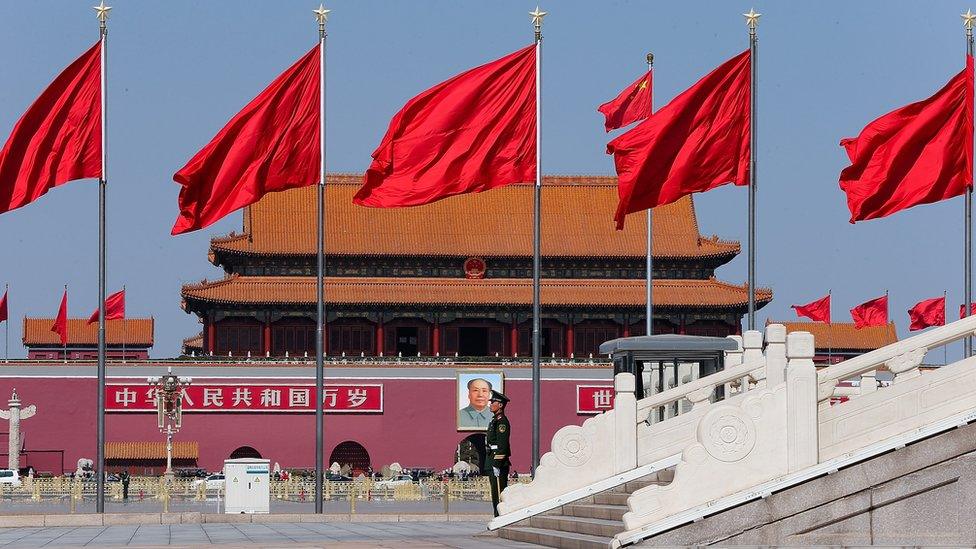

Beijing hopes to control the narrative of how China used to be

So if a show is popular outside China but carries the wrong values, authorities might think it's better to not have it at all.

Beijing is keen to control the narrative of China's past and present.

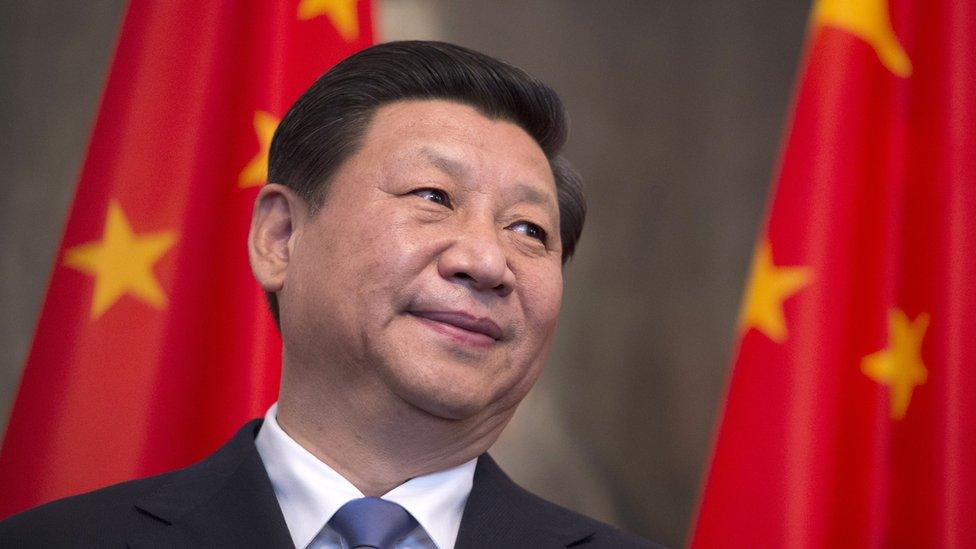

President Xi Jinping is promoting the idea of the rise of China as peaceful, and that China believes in harmony.

Yanxi Palace, though, paints an image of a China of intrigue and backstabbing.

"It flies in the face of the message that China wants to send about its peaceful rise," Mr Rosen says.

Eager self-censorship

With Yanxi Palace still available online, it's unlikely Beijing will be able to undo whatever perceived damage the series might have done.

But the very public criticism sends a signal to future programmes.

Often, it only takes one person from the political leadership to see the show, dislike it and contact the propaganda department to arrange for a critical article to be written.

Once published, everybody knows the criticism has high level backing; then TV channels will very quickly self-censor and drop whatever show has fallen from grace.

"Historical dramas have been popular in China since the 1990s," says Ms Koetse. "And one of the reasons why is that official censors used to have somewhat different standards for them than for the more contemporary dramas."

"But if the focus of one of those programmes is too much on conspiracy, power struggles and conflict, then I can imagine that this is not the message about Chinese history they want to see."

President Xi Jinping wants the rise of China seen as peaceful

For future projects this means that producers will likely be more careful.

Already, anything done for TV or streaming has to be vetted and approved. And producers will be less likely to plan an elaborate historical drama if there's a chance it will get shot down by the censors.

"And censorship is getting tighter, I would say," Mr Rosen says. "It's not just series or movies, it's also targeting music like rap for instance."

Struggling for soft power

China often stands in its own way when it comes to building up its soft power.

A point in case are the movies it enters into the Oscars foreign movie category.

There've been plenty of strong candidates in recent years but those didn't get picked, says Mr Rosen, likely because they tell a story that Beijing thinks reflects negatively on China.

The 2017 movie Angels Wear White dealt with child molestation while 2018's Dying to Survive told the story of a cancer patient illegally importing medicine from India.

Both movies were successful in China and have received international praise - but they don't depict the version of China that Beijing wants to world to hear.

"If they tolerated a little bit more criticism, they could be much more successful when it comes to soft power," Mr Rosen sums up.

"But they worry that once they open the floodgates, they won't be able to retain their control anymore."

- Published23 December 2018

- Published6 February 2019

- Published24 January 2018

- Published11 January 2019

- Published21 June 2018

- Published22 January 2019

- Published24 January 2019