China denies Muslim separation campaign in Xinjiang

- Published

Chinese Ambassador Liu Xiaoming dismisses evidence of a separation campaign in Xinjiang

China's ambassador to the UK has denied that Muslim children in western Xinjiang are being systematically separated from their parents.

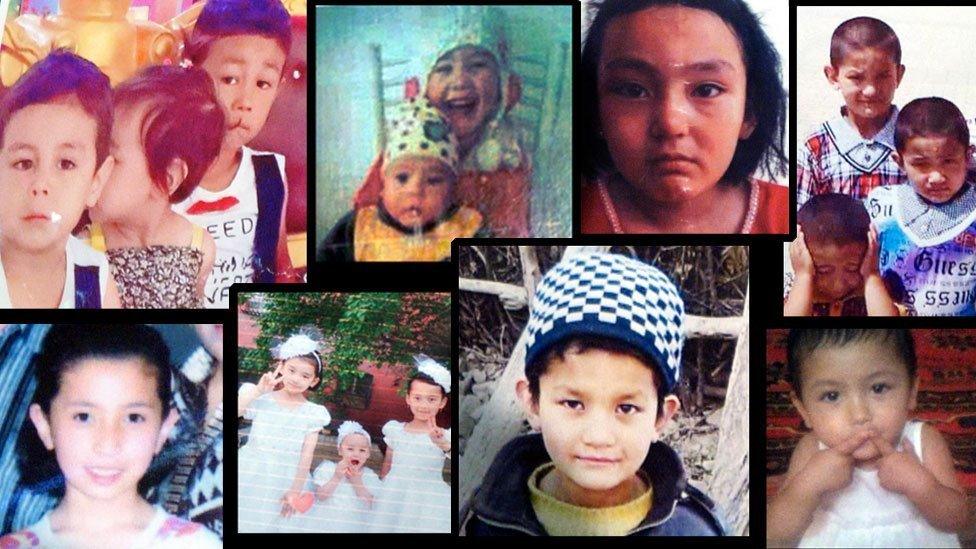

A BBC report found that hundreds of children from the Uighur minority ethnic group had had both parents detained, either in camps or in prison.

At the same time, China has launched a large-scale campaign to build boarding schools for Uighur children.

Critics say it is an effort to isolate children from their Muslim communities.

However, Chinese ambassador Liu Xiaoming dismissed this.

"There's no separation of children from their parents. Not at all," the ambassador told the BBC's Andrew Marr Show on Sunday.

"If you have people who have lost their children, give me names and we'll try to locate them", he added.

Evidence gathered by the BBC showed that in one Xinjiang township alone more than 400 children had lost both of their parents to some form of internment.

Chinese authorities claim the Uighurs are being educated in "vocational training centres" designed to combat extremism.

But evidence suggests that many are being detained for simply expressing their faith - praying or wearing a veil - or for having overseas connections to places like Turkey.

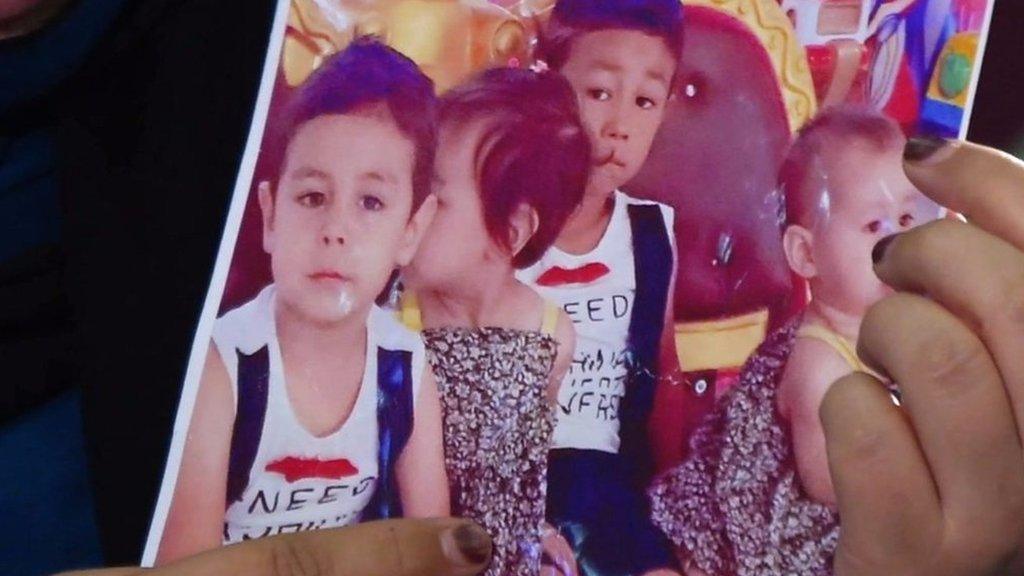

The BBC's John Sudworth meets Uighur parents in Turkey who say their children are missing in China

More than a million people are thought to be held within the system.

After parents are detained, formal assessments are then carried out to determine whether the children need "centralised care".

One local official told the BBC that children whose parents had been detained in camps were sent to boarding schools.

"We provide accommodation, food and clothes… and we've been told by the senior level that we must look after them well," she said.

But Dr Adrian Zenz, who carried out the research commissioned by the BBC, said boarding schools "provide the ideal context for a sustained cultural re-engineering of minority societies."

"I think the evidence for systematically keeping parents and children apart is a clear indication that Xinjiang's government is attempting to raise a new generation cut off from original roots, religious beliefs and their own language," he said.

Dozens of Uighur parents living in Turkey spoke to the BBC about their desire to be united with their missing children.

"I don't know who is looking after them... there is no contact at all," one mother said.

Thousands of Uighurs have moved to Turkey to do business, to visit family, or to escape China's birth control limits and what they call religious repression.

Many stayed after China began detaining hundreds of thousands of Uighurs over the past three years.

Mr Liu, however, described the parents who spoke to the BBC as "anti-government people".

"You cannot expect a good word [from them] about the government," he said. "If they want to be with their children they can come back."

- Published4 July 2019

- Published4 July 2019

- Published8 November 2018