Hong Kong protests: Were triads involved in the attacks?

- Published

A large group of masked men in white T-shirts stormed Yuen Long station

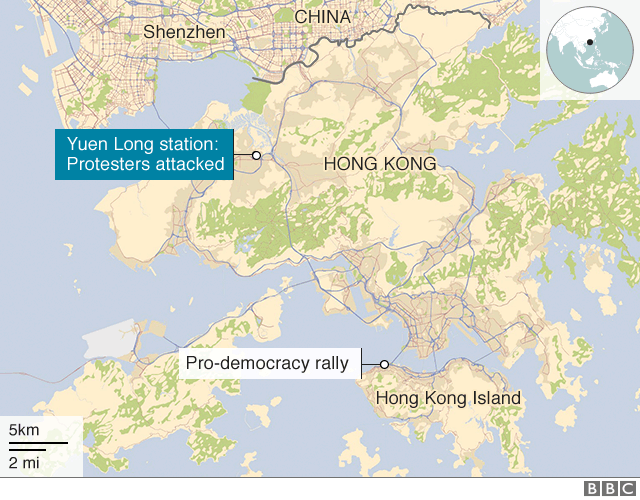

On Sunday, dozens of masked men stormed a train station in Hong Kong - assaulting people returning home after a pro-democracy protest, as well as passers-by, with wooden sticks and metal rods.

The violence left 45 people injured. It shocked the territory, as footage of the brutal attack quickly circulated online.

There has been widespread speculation that the attackers belonged to triads - the name given to organised criminal networks that operate in Hong Kong, and are also known as the Chinese mafia.

But what exactly are triads - and could they have been involved?

What are triads?

Hong Kong's triads are "very localised" mafia groups with their own established rules and rituals, says Federico Varese, a professor of criminology and expert on organised crime at the University of Oxford.

"They usually run protection rackets, prostitution and petty drug dealings - they are not international organisations but are very much present in some local neighbourhoods," he says.

There are several triads in Hong Kong, but particularly notorious groups include the 14K, Sun Yee On and Wo Shing Wo triads.

Triads are hierarchical organisations, with strict codes of conduct and blood brother-like pacts.

While they are mostly active in certain districts in Hong Kong, the phenomenon is well known to locals, and triad activities are often fictionalised - or critics say unfairly glamorised - in local films.

For example Martin Scorcese's film The Departed was a remake of Infernal Affairs, a Hong Kong film about triads.

A victim of Sunday's attacks shows his wounds in hospital

What are triad members like?

Most triad members are working class and have not received higher education, says Prof Varese.

They can be any age - triads not youth gangs - although most members tend to join from a young age, he says.

Young triad members tend to be "recruited from the neighbourhood - you would have people in the local gang keeping an eye on 'promising' youth".

Members undergo a ritual when they are recruited. It traditionally involves chopping the head off a chicken and dripping the blood into a cup which is passed around. The recruits also have the rules of the triad read out to them.

They tend to be naked or half-naked when this happens, because "the idea is you have to forget your previous identity, to join a fictitious family where you are all brothers", says Prof Varese.

"Once you're in, you could be there for all your life," he adds, although some members do move on to run their own businesses, and become "dormant" members.

A South China Morning Post article from 2017, external estimated that there could be as many as 100,000 triad members operating in the city, out of a population of 7.3 million.

In 2018, there were 1,715 triad-related crimes recorded, according to the Hong Kong Police Force.

The majority of cases related to wounding and serious assault, but there were also outbreaks of conflict between rival groups.

Are they thugs-for-hire?

There have been widespread accusations that the groups who attacked protesters on Sunday are paid-for thugs.

It is not the first time such accusations have surfaced.

In 2014, tens of thousands of pro-democracy protesters occupied the streets, in what became known as the Umbrella protests.

A few days into the protest, violence erupted at one of the protest sites in Mong Kok, a working-class district, after attackers punched, kicked and assaulted pro-democracy protesters, while removing tents and barriers they had set up.

Police said 19 of the people arrested had triad backgrounds.

Protesters "feel they are under attack from thuggish elements, potentially triads", reported Carrie Gracie in 2014

Prof Varese and Dr Rebecca Wong from City University of Hong Kong studied the 2014 attacks, interviewing eyewitnesses and two people with triad links - including a senior triad member.

They concluded that the attackers were affiliated with triads outside of Mong Kok, and had been paid to attack the protesters - although some local triads "opposed the attack as they perceived it as an encroachment of their territory".

Informants interviewed by Prof Varesee and Dr Wong suggested that the triads had been paid by "business interests", external that may have wanted to impress the Chinese government.

Triads "might have found a new role as enforcer of unpopular policies and repression of democratic protests in the context of a drift towards authoritarianism in Hong Kong", the report concludes.

Could triads have been involved in Sunday's attacks?

Sundays attackers were mostly dressed in white - and targeted people wearing black, a colour associated with the protesters

There's widespread suspicion that this was the case - and police sources have told the South China Morning Post that they believe the attackers included triad members, external from 14K and Wo Shing Wo.

Prof Varese said Sunday's attack appeared to be a "carbon copy of what happened in 2014", although the attacks appeared to be "more serious" this time since passersby were also attacked.

The objective appeared to be "not to kill but to scare people away" and intimidate protesters, he adds.

"I think it's a deliberate tactic because if they wanted to kill they would kill, although triads are not known to use lethal violence."

It's also notable that in both cases, the attacks took place in working-class neighbourhoods, rather than the central business areas where the protests were focused.

"Triads do not work everywhere. Possibly it is logistically harder to attack areas that are more international, downtown, and diverse."

Are there any connections between triads and the authorities?

Protesters and activists have made such claims before - but the accusations have always been strongly denied by the authorities.

After the 2014 attackers, a top opposition legislator, James To, accused the government, external of using "organised, orchestrated forces and even triad gangs in [an] attempt to disperse citizens" involved in the pro-democracy protests.

The government and police denied colluding with triads, with one police commander calling the claims "ridiculous".

During Sunday's attack, many protesters and pro-democracy legislators accused the police of being slow to act - saying they only arrived at the scene after the attackers had left - and long after the first 999 calls were made.

The police chief has called the suggestions a "smear", saying that the force is stretched from responding to violent anti-government protests elsewhere.

Researchers say thugs-for-hire have been a particularly significant phenomenon in mainland China, external, where local governments rely on criminals "to expedite their projects and extract formal consent from communities".

However, Hong Kong has a separate judicial and legal system from mainland China, and its own local government - and thugs-for-hire are not a common phenomenon there.

Reporting by BBC's Helier Cheung and BBC Reality Check's Christopher Giles.