Coronavirus: Wuhan emerges from the harshest of lockdowns

- Published

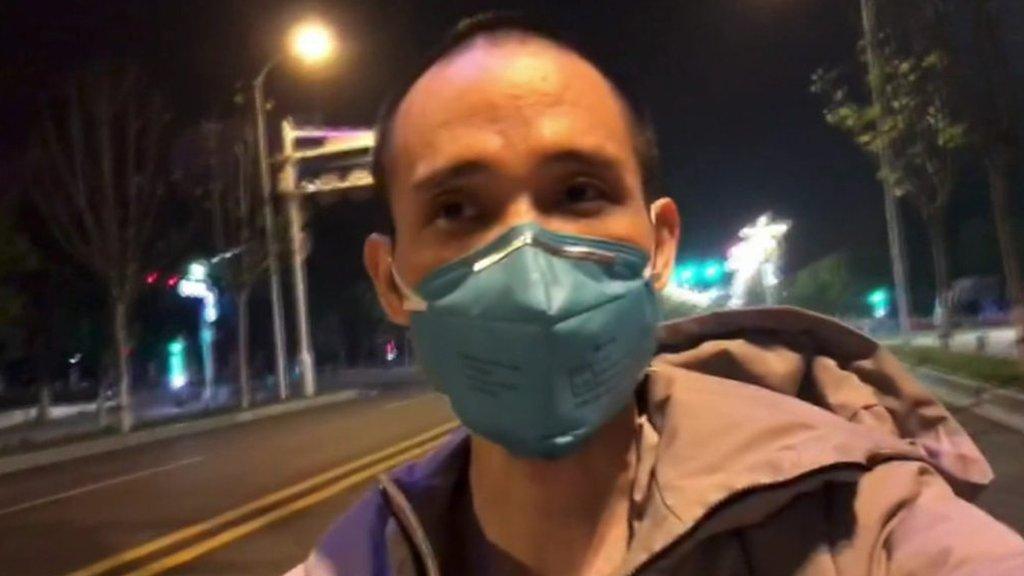

For the first time in months, people have been allowed to leave the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the virus emerged before spreading across the world. The authorities have hailed this moment as a success - but residents had markedly different experiences of what is arguably the largest lockdown in human history.

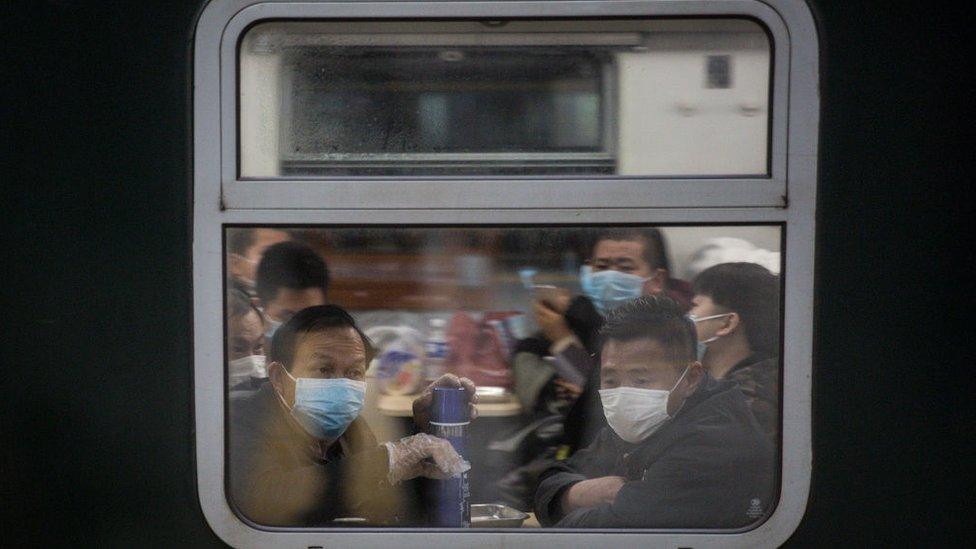

It took 76 days, but Wuhan's lockdown is now at an end. The highway tolls have reopened, and flights and train services are once again leaving the city.

Residents - provided they're deemed virus free - can finally travel to other parts of China.

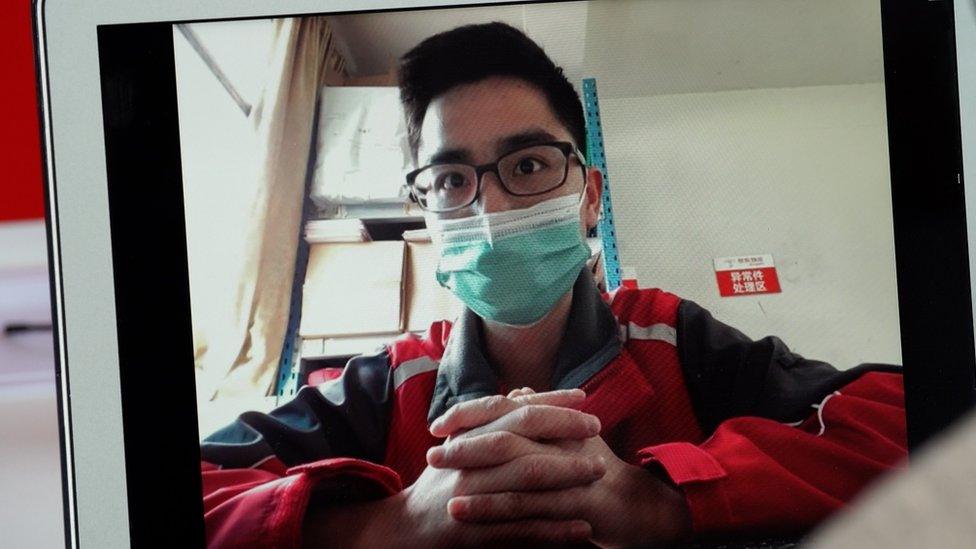

"During the past two months, almost no-one was on the streets," delivery driver Jia Shengzhi tells me.

"It made me feel sad."

Wuhan has endured one of the most extensive and toughest set of quarantine restrictions on the planet. To begin with, people were allowed out to shop for food but by mid-February, nobody was allowed to leave their residential compounds.

Delivery drivers became a vital lifeline.

"We sometimes received phone calls from customers asking for help such as sending medicines to their ageing parents," Mr Jia says.

As the head courier at one of e-commerce company JD.com's Wuhan delivery stations, he worried that such an order wouldn't reach the customer on time if sent via the normal method.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

"So, I rode on scooter, went to the pharmacy, picked up the medicine and took it to his father. "

It's a story of pulling together in a crisis that would be music to the ears of the Chinese authorities.

Anger as criticism muted

But you don't have to look hard in Wuhan to find voices that are not quite so on message.

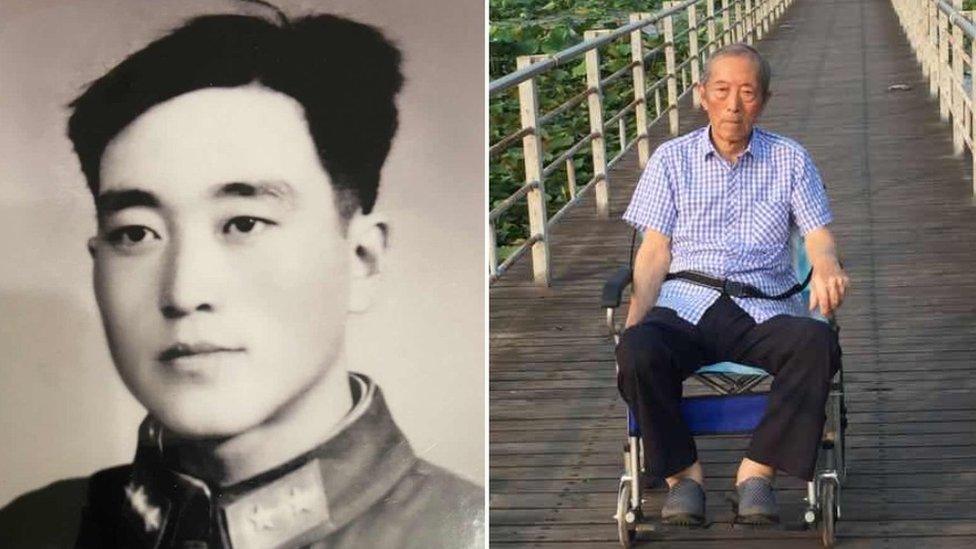

"The cover-up by small group of Wuhan officials led to my father's death. I need an apology," Zhang Hai tells me, before adding: "And I need compensation."

His 76-year-old father, Zhang Lifa, died of Covid-19 on 1 February, having contracted the virus in a Wuhan hospital during routine surgery for a broken leg.

"I feel very angry about it," Mr Zhang says, "and I believe other victims' families are angry too."

In the early days of the outbreak, officials silenced doctors in the city who voiced concerns about the spread of the virus.

But Mr Zhang is particularly angry that, even today, the authorities still appear to be trying to mute criticism of their actions.

Before he could pick up his father's ashes, he says he was told that officials had to accompany him throughout the whole procedure.

"If we were allowed to go unaccompanied then the families would be able meet, discuss it together and ask for an official explanation," he says.

"We also used to have a WeChat group for victims' families, but the police disbanded the group and the organiser was taken to the police station."

Mr Zhang has refused to collect his father's ashes and says he'll do it, alone, at a later date.

"Collecting his ashes is a very private thing, it's a family thing, I don't want other people to be with me," he says.

'Do not blame our government'

Mr Jia, the delivery driver, says none of his family or friends became infected by the virus.

It's a testament to the effectiveness of the lockdown which, despite doubts over the accuracy of the official figures, has undoubtedly slowed the infection rate dramatically.

Over the past few weeks, some of the restrictions inside Wuhan have been slowly relaxed with some people being allowed out of their residential compounds and businesses beginning to reopen.

Now the final step has been taken and Wuhan's transport links to China have been restored.

But although there's evidence that there may be other ways to contain the spread of infection other than harsh lockdowns, both men believe China is on the right path.

"Generally speaking we have won, but we can't become complacent," Mr Jia says.

"All citizens should continue to protect themselves by wearing masks, taking their temperatures, scanning the mobile health code apps, always washing hands and avoiding gatherings."

In the balance between containing the epidemic and restarting the economy, the risk of another spike in infections remains.

Mr Zhang, who blames local officials for his father's death, insists he has no axe to grind with the national government.

Foreign governments though, he insists, are not free from blame.

"Westerners cannot blame our government for their severe death toll," he says.

"They didn't want to wear masks at the beginning dues to their habits... they have a different set of beliefs and a different ideology from us."

- Published11 February 2020

- Published28 February 2020

- Published21 March 2020