China bubonic plague: WHO 'monitoring' case but says it is 'not high risk'

- Published

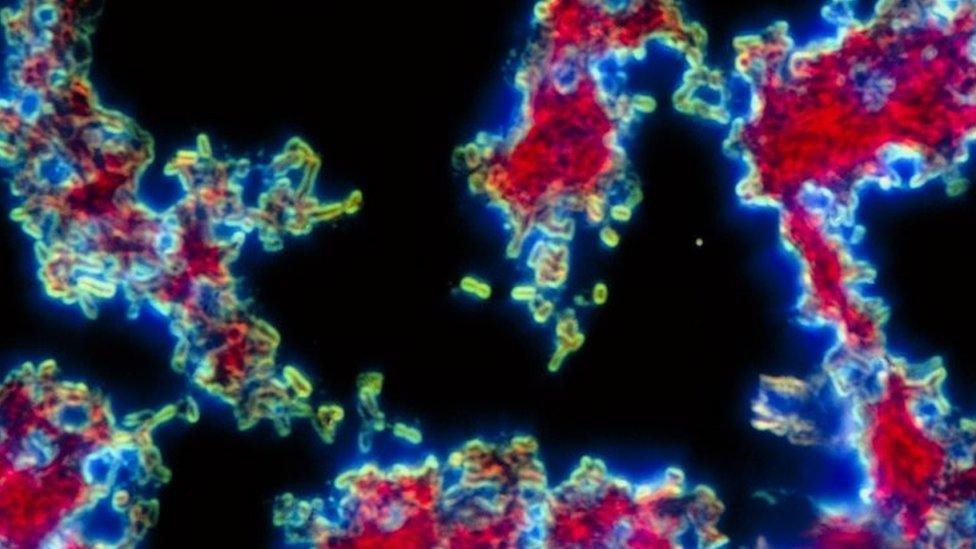

The bubonic plague was once the world's most feared disease, but can now be easily treated

The World Health Organization (WHO) says it is "carefully monitoring" a case of bubonic plague in China's northern Inner Mongolia region, but says that it is "not high risk".

A herdsman is stable in hospital after being confirmed with the disease at the weekend.

A WHO spokeswoman said the case was being "well managed".

The bubonic plague was once the world's most feared disease, but can now be easily treated.

What has the WHO said?

Spokeswoman Margaret Harris said: "Bubonic plague has been with us and is always with us, for centuries. We are looking at the case numbers in China. It's being well managed.

"At the moment, we are not considering it high risk but we're watching it, monitoring it carefully."

The WHO said it was informed on Monday of the case of the herdsman, who is being treated at a hospital in Bayannur.

Chinese news agency Xinhua says Mongolia had also confirmed two cases last week - brothers who had eaten marmot meat in Khovd province.

Russian officials are warning communities in the country's Altai region not to hunt marmots, as infected meat from the rodents is a known transmission route.

Marmot-hunting is banned near Mongolia but goes on despite warnings

What is bubonic plague?

Bubonic plague, caused by bacterial infection, was responsible for one of the deadliest epidemics in human history - the Black Death - which killed about 50 million people across Africa, Asia and Europe in the 14th Century.

There have been a handful of large outbreaks since. It killed about a fifth of London's population during the Great Plague of 1665, while more than 12 million died in outbreaks during the 19th Century in China and India.

But nowadays it can be treated by antibiotics. Left untreated, the disease - which is typically transmitted from animals to humans by fleas - has a 30-60% fatality rate.

Symptoms of the plague include high fever, chills, nausea, weakness and swollen lymph nodes in the neck, armpit or groin.

Could there be another epidemic?

Bubonic cases are rare, but there are still a few flare-ups of the disease from time to time.

Madagascar saw more than 300 cases during an outbreak in 2017. However, a study in medical journal The Lancet found fewer than 30 people died., external

In May last year, two people in Mongolia died after eating the raw meat of a marmot.

However, it's unlikely any cases will lead to an epidemic.

"Unlike in the 14th Century, we now have an understanding of how this disease is transmitted," Dr Shanti Kappagoda, an infectious diseases doctor at Stanford Health Care, told news site Heathline. "We know how to prevent it."

- Published7 May 2019

- Published6 July 2020

- Published15 October 2015

- Published8 September 2016